Britain's EV subsidies are unfair and inefficient

Here's how to make them fairer, cheaper, and cut more emissions

Britain is a nation of motorists. Six in ten journeys start in a car. And when it comes to distance travelled, cars are even more dominant. Just under one-fifth of miles travelled don’t involve a car.

That’s an issue for the climate because the vast majority of those trips will be in vehicles with internal-combustion engines spewing out carbon into the atmosphere from their exhaust pipe. Cars, vans, and lorries are responsible for a quarter of Britain’s total carbon emissions.

Some argue the solution is to get people out of their cars and into alternative forms of transport - this is known as modal shift. This isn’t necessarily a bad idea. Allowing more homes to be built near railway stations and expanding the number of cities with tram networks would cut emissions (and boost growth), but there’s limits to this strategy. There are those who want to go further and block all new road building on the grounds it will ‘induce demand’ and increase road emissions. Not only is this a bad idea economically – roadbuilding increases growth – it is at best a drop in the ocean in terms of emissions.

In fact, when the Climate Change Committee modelled transport decarbonisation they found that modal shift would only deliver 2% of the necessary emissions reductions. The rest would come from decarbonising the fleet. In other words, getting people to switch to EVs.

The challenge is EVs, while cheaper than in the past, are still out of the price range of most Brits. To that end, the Government last week announced a new Electric Car Grant offering up to £3,750 off most new electric vehicles (but not the most expensive ones).

There’s just one problem. Like other schemes designed to promote the uptake of EVs in Britain, it is unlikely to bring emissions down in a cost-effective way. Fundamentally, this is because it's based on a faulty model of how to cut emissions with EVs

How not to subsidise EVs

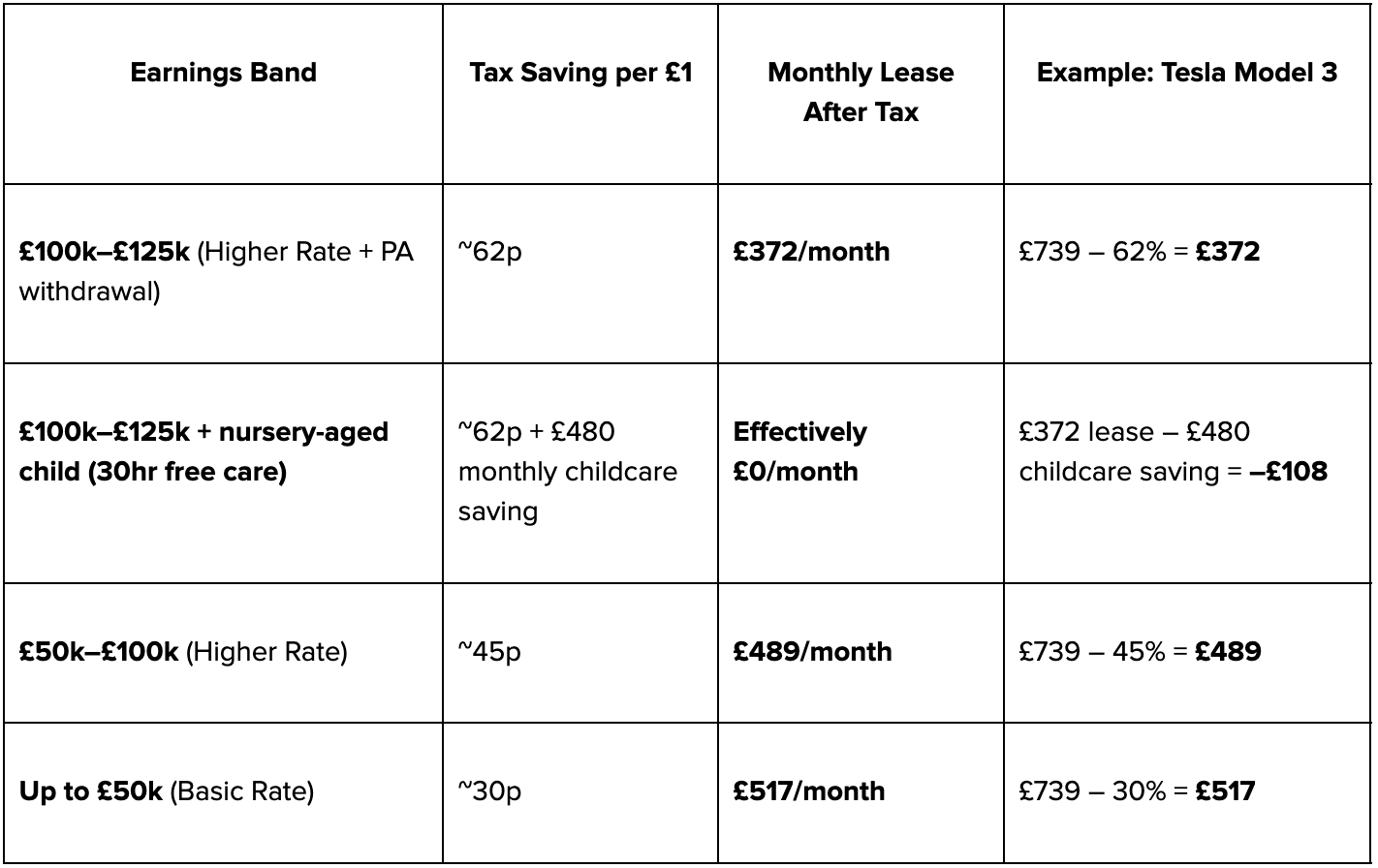

Britain’s tax system is a mess. On paper, we have three rates: 20p, 40p, and 45p. But, if you factor in National Insurance, the High Income Child Benefit charge, Personal Allowance Withdrawal, and 30 hours free childcare, then there are multiple pinch points where higher earners face marginal tax rates of 62p. At the £100,000 threshold, parents with young children are potentially £10,000 or more worse off if they earn a penny more.

Why do I mention this in an article about electric vehicles?

Because the Electric Car Grant isn’t the main way the Government helps Brits afford EVs, rather a salary sacrifice scheme where people can offset the cost of a new ‘company’ car against their taxable income is the UK’s biggest EV subsidy.

And extremely high marginal tax rates have massively increased the incentive to utilise salary sacrifice. For high-earners (£100,000 to £125,000) without young children, there is an effective 62p in the pound discount on new EVs. But if they have young children in nursery, then EVs are not only effectively free, but a £7,200 annual lease on a brand new Tesla leaves you better off even if you leave it in your garage. That’s because earning a penny over £100,000 immediately locks you out of major childcare benefits.

Part of the initial rationale for subsidising EVs was as a proof point. In essence, showing to people that EVs work and can be a good deal. This, in turn, created incentives to invest in complementary sectors. For example, EV chargepoint installers had a reason to invest in new charge points before EVs became price-competitive with ICE vehicles. Companies like Octopus had reason to develop bespoke products to make at-home charging a better deal. In essence, it solves a chicken-egg problem where people won’t buy EVs due to range anxiety and companies won’t install charge points because there are too few EVs.

There’s an added rationale for subsidising EVs for high earners. Most people buy cars second-hand. And most cars leased through salary sacrifice schemes end up on the second-hand market. In essence, subsidising EVs for high earners leads to cheaper cars for middle-earners. By contrast, grants for heat pumps (disproportionately used by well-off homeowners) benefit that household only. There are no second-hand heat pumps.

But times have changed. Britain still hasn’t got perfect coverage for public chargers, but coverage is much better than it once was. And EVs are no longer a tiny share of the market. 20% of new cars sold are EVs. The stock of EVs is growing fast – increasing by nearly 40% in the last year.

Most importantly, we’ve reached the crossover point, some new electric vehicles are now cheaper than their petrol equivalents. When you factor in fuel savings, EVs are an attractive proposition.

(It’s worth noting though that new cars are more expensive in general and people are keeping their cars for longer.)

Mileage matters

The fundamental reason we incentivise EV ownership is because EVs have no tailpipe emissions. EVs cut carbon emissions only so far as they displace miles driven by petrol or diesel cars. This is important because at the moment policy isn’t targeted on usage. Yet not all cars are driven the same amount.

Cars driven professionally, such as private hire vehicles, are driven a lot: in fact, a Black Cab gets 30,000 miles a year, an Uber driver in London does about the same and a minicab outside the capital gets around 34,000.

Vans are well-driven too. Your average Ford Transit will do 9,500 miles a year. Some do a lot more. But crucially, owing to the diesel engine and weight of the vehicle these miles will be around one and half times more carbon intensive than the average mile driven. Vans, diesels in particular, also have a big impact on air-quality. One of the big problems with air pollution is particulate matter from brakes and tires. EVs don’t just emit less from the tailpipe, but also cause less particulate pollution on account of their more efficient regenerative braking systems.

Your average privately-owned car used for commutes and the school run puts far fewer miles on the clock each year. More like 7,000. If you are fortunate enough to own two cars, then chances are you won’t be driving them as often. Single car households do 8,000 miles each year while dual (or more) do 6,500 per car. If you live somewhere with good public transport links then unsurprisingly you drive a fair bit less. Londoners with access to regular buses, trains, and the tube drive their cars 4,560 miles a year, while car-centric Teessiders will drive more than twice as far in a year.

If your aim is to cut emissions, then the priority should be to get cabbies and van drivers to switch. Every switch from ICE to EV cuts emissions, but a multi-car household in London buying a new EV will have a much smaller impact on emissions than a cabbie or van driver making the same switch.

Here’s the problem: our existing EV incentives and subsidies, neither salary sacrifice nor the new Electric Car Grant, are targeted at minicab drivers or white van man. And in the case of salary sacrifice, are most generous for high earners, who happen to disproportionately live in London, and probably own multiple cars.

We spend about £350m a year on the salary sacrifice scheme, while £650m has been earmarked for the Electric Car Grant over the next three or so years. If we targeted that money better–at cabbies or van drivers–it would do a lot more to reduce emissions.

What’s fair?

There’s a fairness issue too. At the moment, the largest tax incentives go to very well-off households. When it comes to salary sacrifice, there’s no cap on that benefit either. At a time of constrained finances with painful cuts on the table: is spending hundreds of millions each year on discounted Teslas for the rich a good use of public money?

Treating £120,000 Tesla Model Xs like £30,000 Nissan Leafs also undercuts the used car rationale. Buyers who can’t afford new cars are unlikely to shop at the most expensive end of the used market. A used Tesla EV is still at the upper end of the price range of most used car buyers. Just like a used Jaguar ICE is at the upper end of the price range of most used car buyers.

The new Electric Car Grant is at least restricted to cars that sell for £37,000 or less. But, while that avoids the absurdity of subsidies for luxury cars, we are still providing grants to buy vehicles that cost as much as the average worker earns in a year.

The issue of fairness goes deeper. Britain funds its roads through high taxes on fuel duty. EVs, which don’t use fuel, don’t pay fuel duty. We are offering regressive tax breaks and grants to promote the purchase of a vehicle that itself is taxed in a highly regressive way.

EVs are crucial for decarbonisation and it's right to want to incentivise their uptake, but the way we are doing it is unfair and inefficient.

The case for shifting EV subsidies towards heavy users like Private Hire Drivers and White Van Man

Under the current system of ‘salary sacrifice’, high-earners can access large subsidies for switching to an EV.

To reiterate, this scheme is not targeted:

There is no added incentive to switch (beyond it being cheaper to run) for the people who drive the most (e.g. minicab drivers). In fact, because minicab drivers are self-employed, they are unable to access the salary sacrifice benefit at all.

There is no cap on vehicle prices — in effect, subsidies are greater for high earners buying Teslas than for middle earners buying a BYD or Nissan.

There is no income targeting – the people best able to afford EVs get the largest subsidies.

At the moment, the scheme costs the Exchequer around £300 million per year. A combination of fiscal drag — people being pulled into higher tax bands due to inflation — and EVs becoming more attractive is set to push the cost of the scheme to £600 million a year by the end of the Parliament.

The Electric Car Grant is cheaper and more targeted, excluding the most expensive EVs, but other countries show it is possible to design a scheme that delivers much more bang per buck.

By contrast, France’s main scheme for encouraging EV uptake–known as social leasing–is highly targeted.

It is only accessible to the people who drive more than average: you must drive at least 8,000 miles a year to access it.

There is a cap on vehicle prices. The most expensive luxury EVs (such as Tesla Model 3s) do not qualify.

It is only available for low-earners.

Consumers pay between €50-€150 per month to lease their EVs under the scheme.

On average, the Exchequer forgoes £9,000 in revenue per vehicle via the UK’s Salary Sacrifice scheme. In France, subsidy per vehicle can reach £11,000 over a three-year lease. By restricting the subsidy to lower earners, the policy is less likely to subsidise purchases that would have been made regardless of the subsidy.

Even though per vehicle subsidies can be higher under the French scheme (on average), it delivers a much larger reduction in emissions because it is targeted at heavy road users. Let’s compare two typical motorists using each scheme. In France, let’s assume they drive around 8,000 miles each year (just over the cut-off to use the scheme). And let’s also assume this vehicle will be driven around that much for a decade. At the current carbon intensity of the grid, over that decade the car will spew out 22 fewer tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere compared to an ICE.

Let’s compare that to a car that is subsidised under Britain’s salary sacrifice scheme. A £110k earning Londoner will drive it about 4,560 miles each year. Let’s be generous and round-up to 5,000 miles. That means over a decade the car will spew out around 14 tonnes less. The hope is that at the end of the three year lease the car is sold to someone who will clock up more miles.

On an emissions cut per pound basis, the French scheme appears to give you about 30% more bang for your buck. This is, in fact, a massive understatement. What the above comparison didn’t do was factor in embedded carbon, that is, the carbon used making the EV in the first place. If you use an industry standard figure of 8 tonnes then it changes the picture significantly. The French scheme isn’t 30% more cost-effective, it is twice as effective.

Of course, the above example uses the minimum qualifying mileage for the French scheme. The higher the mileage they rack up the bigger the emissions saving per pound. If a cabbie clocking up 20,000 miles a year switches to an EV then it generates a massive eight times larger emissions reduction over a decade than persuading our well-off Londoner to get a Tesla.

What could a UK scheme look like?

Britain should take a leaf out of France’s book. Instead of supporting the switch to electric vehicles via tax breaks, which arbitrarily gives the largest incentive to switch to an EV to someone on a £110,000 salary with a two-year old in nursery, or doling out blunt subsidies that are better but not much better, we should create a capped French-style scheme aimed at people who have no choice but to drive a lot.

The new incentive should build upon the French scheme in two key ways:

It should only be open to motorists who have driven a minimum of 12,000 miles in the last year and have a job that requires them to drive.

It should be limited to affordable vehicles with only cheaper EVs (£37,000 or less) qualifying as is the case for the newly announced grant. In other words, no more subsidies for Jaguars or Teslas.

To fully decarbonise our roads, we will need every motorist to switch to zero-emission vehicles. Eventually, we will get there, but we are a long way from there at the moment. In the medium term, the focus should be on supporting the most impactful switches.

There’s a good reason to target people like minicab drivers with incentives: It works. Even relatively small targeted incentives, like London’s Congestion Charge exemption for EVs, have had big impacts. Even though the Congestion Charge saving only amounts to £3,750 per year for an Uber driver (assuming they work 250 days a year), it has been the driving force behind Uber drivers switching to EVs at around eight times the rate of the general public.

Beyond fairness, there’s another reason to target less well-off heavy-mileage drivers. There’s a good chance switching to an EV will be cheaper for them over the long-term, but financing that upfront payment is the hurdle. For high-earners leasing EVs through salary sacrifice, the big benefit of switching is getting a shiny new toy that drives fast and they can feel smug about. For a rural care worker who can’t do their job without driving, it’s a huge cut to one of their biggest monthly outgoings. In fact, a survey from climate campaigners Possible found almost a third of rural care workers spent more than £150 a month on driving for work alone. Even with the UK’s high electricity bills, that rural care worker is looking at least a £500 a year saving by switching.

Look, if our sole aim was to help the low-paid then we’d be better off just giving them the cash. But as an added bonus for a policy aimed at cutting emissions, it’s not bad is it?

Going even further

Britain’s current strategy for getting motorists to switch to clean electric vehicles is relatively simple. Force carmakers to sell more EVs and fewer ICE year by year, sweeten the deal with generous tax relief for leasing EVs, and pray the EVs trickle down into lower-income driveways through the used car market.

This article has argued for a different approach, at least in the short term. To cut emissions faster we need a targeted approach: one that doesn’t treat all EV switches as equally valuable. At the moment, we treat a corporate lawyer in Hampstead trading in their Porsche for a Tesla as much more valuable than getting a minicab driver in Yorkshire to trade their Skoda for a Nissan Leaf. I This should change. Money for EVs should go to people who are most reliant on their vehicles from rural care workers and mini-cab drivers to ‘White Van Man’.

It may seem that the logical conclusion of the approach advocated above is to work down from high-to-low mileage users. Eventually (and this might not be too far away), we end up with a system that looks a bit like what we currently have but with less subsidy as EV costs fall. But I think the deep insight that its miles driven (not vehicles sold) that matters implies something else.

What if there was another way to shift more of our collective national mileage to electric vehicles? In the car-centric US, the rise of Uber led some people to ditch their cars altogether and rely on the app to get around. Because Ubers and Lyfts are high-mileage vehicles, drivers typically pick the most fuel-efficient vehicles. For a long-time, that was a hybrid Toyota Prius. It may now be an EV. In other words, ‘ridesharing’ is green. The big barrier to scaling that strategy is that cab fares aren’t cheap. After all, fares have to pay for not just maintenance and fuel, but crucially the person sitting in the driver’s seat. But what if they didn’t?

Experts predicting that driverless cars would be on British roads by 2020 look pretty silly in 2025. But while driverless cars may have been over‑hyped in the past, they increasingly look like the real deal. In San Francisco, more than 3.8 million rider‑only miles have been ‘driven’ by Waymo taxis without a human driver. In Arizona, it’s 7.1 million – and with way fewer accidents per mile. Driverless trucks are now cleared to be driven on roads in Texas.

Britain is a laggard. Driverless car regulations are still a few years off, but we do have a world-leading firm in Wayve and Uber have just announced they’ll be trialling a driverless taxi service in London next year.

Switching to an EV is a big financial decision, but leaving the car at home and getting a cheap ride in a driverless cab isn’t. Getting Britain up to speed on driverless cars isn’t just about cutting car crashes or saving the country pub, it could be key to getting the nation’s motorists into EVs.

Quite an extensive article but the whole premise is wrong.

Carbon Dioxide emissions do not need to be reduced at all, (Please, not Carbon, don't be lazy, or is that so as to make it sound dirty?) and do not rely on anything the Climate Change Committee claim, they are very much wrong on just about everything.

Another misconception is that electric vehicles do not contribute to such emissions, generating electricity produces a lot of CO2, they would, should the uptake increase in line with government wishes, need much more gas generation to charge them than even now. (Renewables cannot react to the extra load)

I expect you will disregard my view but it is a lot more realistic than the current fashionable view that many hold.

Carbon Dioxide in our atmosphere is a very minor player in influencing climate.

How many are aware that H2O is significantly stronger (X 500 or so more in concentration and absorbs and re radiates the whole infra red spectrum, while CO2 traps only a small part of it).

We have and continue to destroy our prosperity, exactly as some desire, the United Nations and the World Economic Forum, to name two, largely due to using renewables to make us one of the world leaders in expensive electricity. Expensive transport and home heating is another contributor, all for no gain whatsoever.

Also on £37k price limit; for EVs at this price point, range and size may become a problem preventing uptake, especially for cab drivers, trades, etc.