Britain's infrastructure is too expensive

Railways, Trams, and Roads all cost more to build in Britain

“Unachievable.” The Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s assessment of High Speed 2 (HS2) does not pull its punches. Back in 2013, the high-speed line to connect London, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds was estimated to cost about £56.7bn in 2023 prices. But this proved to be a massive underestimate. The 134 miles of track between London and Birmingham alone is now forecast to cost £53bn, and at £396m per mile Phase 1 of HS2 is one of the world’s most expensive railways.

Some of the mismanagement of the project would be comical, if it wasn’t so tragic. Take the recent news that two multi-million pound tunnel boring machines will be buried at Old Oak Common until a decision about whether to extend the line to Euston station is reached.

Much has been written about how HS2’s budget grew so large. Yet even if the 2013 estimate had been correct, HS2 would still stand out. At £165m per mile, it would still be more than double the price Italy is paying to build a high speed connection between Naples and Bari. It would also be 3.7 times more expensive than France’s high-speed link between Tours and Bordeaux. One reason HS2’s cost is high is the amount of tunneling involved, yet in Japan, bullet trains travel on Hokkaido’s new Shinkansen line built at just £50m per mile despite almost half of the Hokkaido line being tunneled.

It would be unfair, however, to single out HS2. Britain Remade, the pro-growth campaign group where we both work, has looked at 138 tram, metro, and rail projects across 14 countries (data) plus 104 road projects in 11 countries (data).

The reality is that infrastructure of all kinds, from railways to roads, tramlines to tubes, is more expensive to build in the UK.

NB. To allow for comparison over decades, all figures for cost (except stated otherwise) have been inflation adjusted to 2023 GBP.

Trams

In the last 25 years, France has built 21 tramways. Avignon, Besançon, and Caen have all seen tramways out of use since the 1950s, rebuilt and reopened in the last decade. All three places have tramways despite having fewer than 150,000 residents living in their city proper. None of them have more than 500,000 people living in their wider metropolitan area. In population terms, it is the equivalent of Lincoln, Winchester, and Carlisle all having tram systems.

Infamously, Leeds is the largest city in western Europe without a metro system. Over 530,000 people live in the city but have to make do with buses. Another 300,000 or so live in the wider metropolitan area and have to choose between an unreliable local rail network or congested roads.

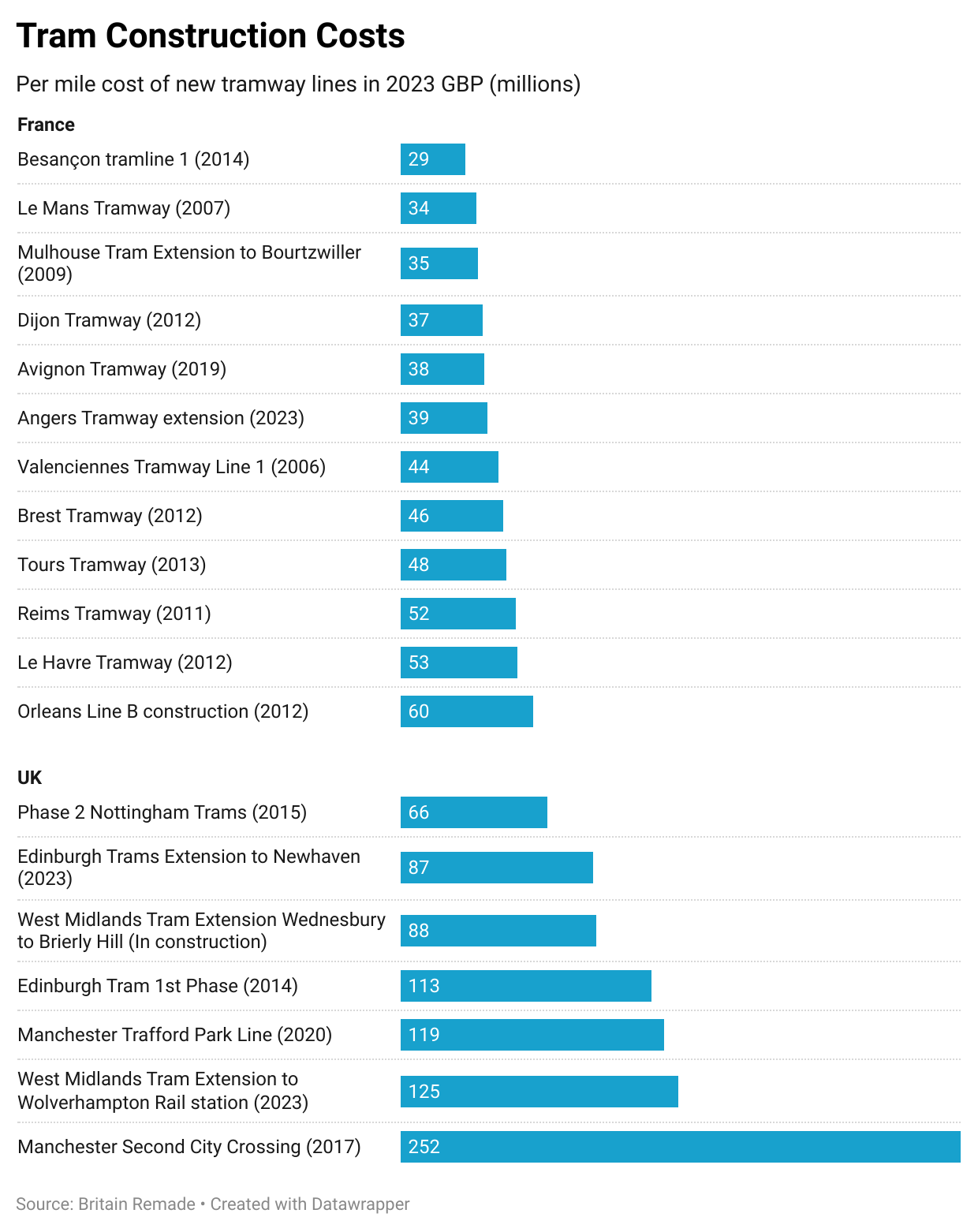

So how has France been able to have a tram renaissance, and why can’t Britain do the same? Britain Remade has looked at 21 tram projects in Britain and France. After adjusting for inflation, we found that tram projects in Britain are two and a half times more expensive than French projects on a per mile basis.

Leeds saw a proposed “Supertram” cancelled in 2005 after construction costs doubled to £1bn (£1.6bn in 2023 prices). On a per-mile basis, it would have been more than 2 times more expensive than the average French tramway (though still cheaper than most recent British projects).

What about the trams Britain has actually built in recent memory? There’s Edinburgh’s controversial tram. The 11.5 mile project cost £1bn and took 12 years to finish. More than £13m has been spent on an inquiry into how a project that in 2007 was estimated to cost £375m (for an initial 14.5km) more than doubled to £776m when it opened in 2014 - a cost of £87m per mile.

Or take the Trafford Park Line extension to Manchester’s Metrolink. The 3.4 mile extension completed in 2020 cost £406m to build. That’s £119m per mile. Not as much as the £252m per cost of Metrolink’s Second City Crossing through Manchester city centre, but still 4 times more per mile than Besançon’s tramway.

The West Midlands Metro was meant to have been extended from Wednesbury to Brierley Hill by 2022. It now will only go 4 miles to Dudley and won’t be completed till 2025 at the earliest. Later stages of the project are in doubt after the 6.8 mile project’s total cost grew by over £100m to £550m (£89m per mile).

Nottingham’s phase 2 extension is a rare bright spot for British trams, coming in at £66m per mile, which is the cheapest of any of the British trams covered. However this is still £6m more than the most expensive French tramway covered, Orleans’s Line B.

Some French projects stand out. Besançon’s tramway cost just £28m per mile and was built six months ahead of schedule. How were they able to keep costs so low? They rejected complexity at all stages and focused on standardisation wherever possible. Over 40,000 passengers ride the trams in Besançon each day and an expansion is underway to deal with overcrowding. In some cases, French cities work together on procurement to cut costs further.

Tubes

The Elizabeth Line is a roaring success. Only months after opening, it has become the busiest railway in Britain. At peak time, it moves around 36,000 people per hour. Building the Elizabeth Line (also known as Crossrail) was undoubtedly the right decision. Yet at a cost of £15.8bn (£18.1bn in 2023 prices) for just the core central tunnelled section from Paddington to Abbey Wood and Stratford, it is one of the world’s most expensive metro systems. Only New York can beat its staggering £1.392bn per mile cost.

The recent Northern Line Extension to Battersea was less expensive, but at a cost of £1.1bn (£1.26bn in 2023 prices) for just two miles of track it certainly wasn’t cheap.

After adjusting for inflation, a few places standout. New York in the US is by far the world’s most expensive place to build. Yet, Britain does not do well either. At a cost of £676m per mile, British projects are 2 times more expensive than projects in Italy or France, 3 times more expensive than Germany, and a whopping 6 times more expensive than Spain.

In the space of just eight years, Madrid built an entire 81 mile subway network at just £68m per mile. To put that into perspective, that’s nine times cheaper per mile than the Jubilee Line Extension built at roughly the same time. Infrastructure expert Bent Flyvberg attributes their incredible achievement to inexpensive standardised station designs, a reliance on tried-and-tested technology, and an approach to construction that prioritised speed. For instance, instead of hiring one tunnelling machine, they hired six and worked around the clock. Community groups were persuaded to accept this approach when the choice was framed as “a three-year or an eight-year tunnel-construction period.”

More recently, Bilbao completed a new metro-line in 2016 at a cost of £90m per mile. Barcelona, by many metrics Europe’s densest city, added almost 30 miles of new underground line at a cost of £200m per mile. More expensive than other Spanish projects but still extremely cheap by London’s standards.

Spain stands out for their ability to build metro systems cheaply, but many places are able to build cheaply compared to the UK. Take Copenhagen, Denmark, which opened the 9.6 mile City Circle Line in 2019. At a total cost of £3.4bn or £350m per mile, the driverless line is nearly twice as cheap as the Northern line extension. Sweden, Norway, and Finland are all either constructing or have recently completed projects for even less.

If Britain could build as cheaply as Spain and the Nordics, a much wider range of transport would be affordable. Alon Levy, who researches the cost of building public transport infrastructure, created a map of what would be possible in London at Nordic costs. Instead of debating whether to build Crossrail 2, we would be ploughing onto Crossrail 3, 4 and 5.

London’s high costs make further underground rail systems seem unaffordable to the rest of the country. Yet if we could build at Nordic (or even better Spanish) costs, then a range of projects would open up. As well as Leeds, Bristol stands out as a large city without a metro system. Bristol’s council have been investigating the possibility of building an underground rail system, yet if the cost is £18bn as one consultancy’s report put it or even just the £7bn Bristol’s Mayor puts it at then the project’s a non-starter.

Rail Electrification

In many northern towns and cities, rail links are crowded and unreliable. Part of the problem is clearly to do with our model of rail franchising where TOCs are not financially penalised for cancelling services at short notice. Yet, the infrastructure itself is a major problem too. Too few lines are electrified forcing commuters to rely on slower, dirtier, and less reliable diesel trains. Key routes such as Manchester to Sheffield, Leeds to Manchester via Bradford, and Leeds to York via Harrogate are still waiting for electrification.

The UK is a laggard on rail electrification. More than two-thirds (71%) of Italy’s railways are electrified, while less than two-fifths (38%) of ours are. Germany (61%) and France (55%) both do better than us.

Electrifications should be a no-brainer. In the long-run, it will almost certainly reduce the costs of running the railways with environmental and reliability benefits to boot. When the Coalition entered office in 2010, they had bold plans for rail electrification. Yet schemes to electrify consistently went over budget.

Take the electrification of the Great Western line from London to Swansea. The project’s budget expanded threefold. As a result, electrification from Cardiff to Swansea was curbed and the Midlands Mainline Upgrade scheme was cut back.

Research from the Rail Industry Association highlights that electrification is delivered at a much lower cost in Germany, Switzerland and Denmark. In fact, they estimate that rail electrification can be delivered at between 33%-50% as cheap as many projects stretch to.

One electrification project stands out as an example of everything Britain does wrong on infrastructure. The TransPennine Route Upgrade was designed to electrify the 76 miles of railway connecting York and Leeds to Manchester. When it was first envisioned 12 years ago, it was budgeted to cost £289m and finish in 2019. Yet, a chaotic process means that costs have ballooned to between £9bn-£11bn and the North West is still waiting for the upgrade.

In an FT column, Tim Harford explains what went wrong:

Ministers have vacillated endlessly over the specifics as personnel and budgets changed. Work was started in 2015, then paused almost immediately while waiting for Network Rail’s investment programme to be reviewed. When it restarted later that year, the aims of the project had changed: the line now needed to accommodate more passengers on faster, more frequent and more reliable trains. A further rethink committed the upgrade to laying extra track, enhancing the station platforms and introducing digital signalling.

The current project is not necessarily the wrong one, but the constant changing of scope means that almost £200m has been spent on completely unnecessary work. Almost two-thirds of the cost of the initial electrification programme wasted.

Roads

What about roads? Britain is closer to its international peers on this front. Looking across 104 projects in 11 countries (data), Britain is 23% more expensive than France, 17% more expensive than Canada, and 13% more expensive than Italy. We effectively rank mid-table with Australia and Sweden more expensive than us.

That’s the average at least, but there are a number of projects that are extremely expensive by international standards. Take the Lower Thames Crossing, a vital project to improve transport between Essex and Kent. It is set to cost £9bn (or £700m per mile). Tunnelling underneath the Thames with the unique geographical challenges it poses is never going to be cheap, but some things stick out.

The project was originally budgeted to cost £4.3bn yet the cost has grown massively to £9bn. Why has the cost grown so much? One reason is inflation, which is currently running high for energy intensive activities such as construction, and would have been entirely avoidable had the project started earlier. The LTC’s been stuck in a marathon planning process. Over five consultations have taken place since 2013. If construction started in 2013, there is no doubt the project would be cheaper.

More than £250m has been spent on the Lower Thames Crossing’s 63,000 page planning application. In effect a quarter of a billion spent so one branch of government can ask another branch of government for permission with no guarantee of success.

To put that figure into perspective, that’s more than double the cost of building Norway’s Laerdal tunnel, the longest road tunnel in the world.

In fact, Norway built the world’s longest road tunnel and the world’s deepest subsea tunnel for less than the LTC’s planning application. Norway’s geology is favourable for tunnelling, yet this comparison isn’t tunnelling under the Thames versus tunnelling under Norway’s hard rock. It is applying for planning permission to tunnel under the Thames versus actually tunnelling in Norway. In fact, Norway often tunnels at a lower cost than Britain builds roads above ground.

Take the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon. By most accounts, this was a fairly successful road project. It certainly is popular. At a recent roundtable that Britain Remade hosted, multiple Cambridgeshire-based businesses brought it up and praised it. It provided 21 miles of widened or new dual carriageway for £1.6bn. Let’s compare that to Norway’s Ryfast and Eiganes tunnels – 14 miles, 290m under the sea through solid rock at a cost of around £700m.

The UK is spending £500m adding a lane to the existing 4 mile A46 Newark bypass, for the same cost Germany built 14 miles of new 6-lane motorway and refurbished another 14 miles as part of the A4 Autobahn.

One reason for Britain’s high costs in construction may be the result of NIMBY power. National Highways have a page where they detail all of the changes and design upgrades done in response to the Lower Thames Crossing’s five consultations. For instance, the tunnel was widened to three-lanes instead of two. The tunnel entrance was moved 950m away from the river. Three additional green bridges have been added as well. The overall height of the road has been reduced by as much as five metres and 80% of the route is now in a cutting, false cutting or tunnel. All of this makes for a better road, but it also makes for a much more expensive road.

America is even more expensive for infrastructure than us. US economists who have looked at the issue of infrastructure costs there attribute the tripling in road building costs between the 1960s and the 1980s to the growth in ‘citizen voice’. As it has become easier to block a project, roadbuilding has become more expensive to accommodate more cuttings, tunnels and more circumspect routes. In fact, new highways in the US have become wigglier as they design routes to avoid vocal opponents.

Costs matter

The more expensive infrastructure is to build, the less of it we can afford. Brits are less productive as a direct result. Outside of Britain, bigger cities tend to be more productive. Employers are drawn to large pools of labour, while workers are able to specialise into really specific jobs in the knowledge that if it doesn’t work out with one employer, there are still plenty of options open to them. Yet, London aside, bigger does not appear to be better in Britain.

One explanation for why Britain's big cities underperform is that they’re only big on paper. In most European cities, around two-thirds of residents can get to the city centre by public transport within 30 minutes at rush hour. In British cities, it is more like two-fifths. And in Leeds, Birmingham, and Manchester, it is even fewer. New tram lines, new tubes, and faster, more reliable electrified railways could change that. If they were as cheap to construct as they were in Europe then they would be a lot more likely to actually get built.

What you fail to take into consideration a key block to cost effective construction - it is that the whole construction market in the UK is designed to increase cost - the “main” contractor subcontracts out each and every element, the award of contract is based on price - with scant regard for the ability of the subbie to complete the works - this leads to increased costs rectifying low quality workmanship. The days when a company employed its own workforce are long gone, it is only the SME’s that do this today, the company has no interest in the myriad of works that go into the whole - it is price and price alone. The contracts they sign are never fixed price, they are linked to material price index’s, so whilst the price they secure the project at may appear unrealistic, it is never what they end up getting paid which is always higher due to unforeseen price increases - meanwhile the subbies are contracted to complete works on a fixed price - in many cases these subbies fail, and replacements are appointed, does the main contractor care, no, the “failed” subbie does not get paid for the works done - more cash to the main contractor.

If you want to get a major project built, on time, to spec, then you need a fixed, unmovable price to be agreed, the contractor then knows that the days of padding increases are over and they are on the hook for delays. This will encourage direct employment of trades, bringing both security to tradesmen and an uplift in work quality. Failing that, only employ German, Norwegian or French companies from start to finish - they at least have the experience and direct employed workforce to get the job done - on time, on budget.

In addition to the failures around procurement relating to subcontracting is the practice of tendering work piecemeal; HS2 being a case in point. The work was tendered in 3 parts, with different companies winning the tender to deliver separate legs. This meant that delivery couldn't proceed as in France, for example, where standard practice is to build the line from both ends simultaneously, meeting in the middle. This permits moving heavy machinery and plant around on the newly laid track, obviating the need for expensive and destructive construction of access roads, which are a major cost driver on HS2.

It also increases risk and difficulty in the areas where the different segments must be joined up, as the various contractors need to coordinate between themselves to ensure alignment.

[edit to add]

Procurement failures are a major driver of cost for UK infrastructure projects and the Civil Service is extremely poor at it. This is primarily because the current wage structures do not allow them to hire people with the engineering or legal expertise to procure complex technical proects and negotiate contract effectively.