Britain’s latest renewables auction locks in higher prices.

Britain just bought 8.4GW of wind power. Expect bills to go up.

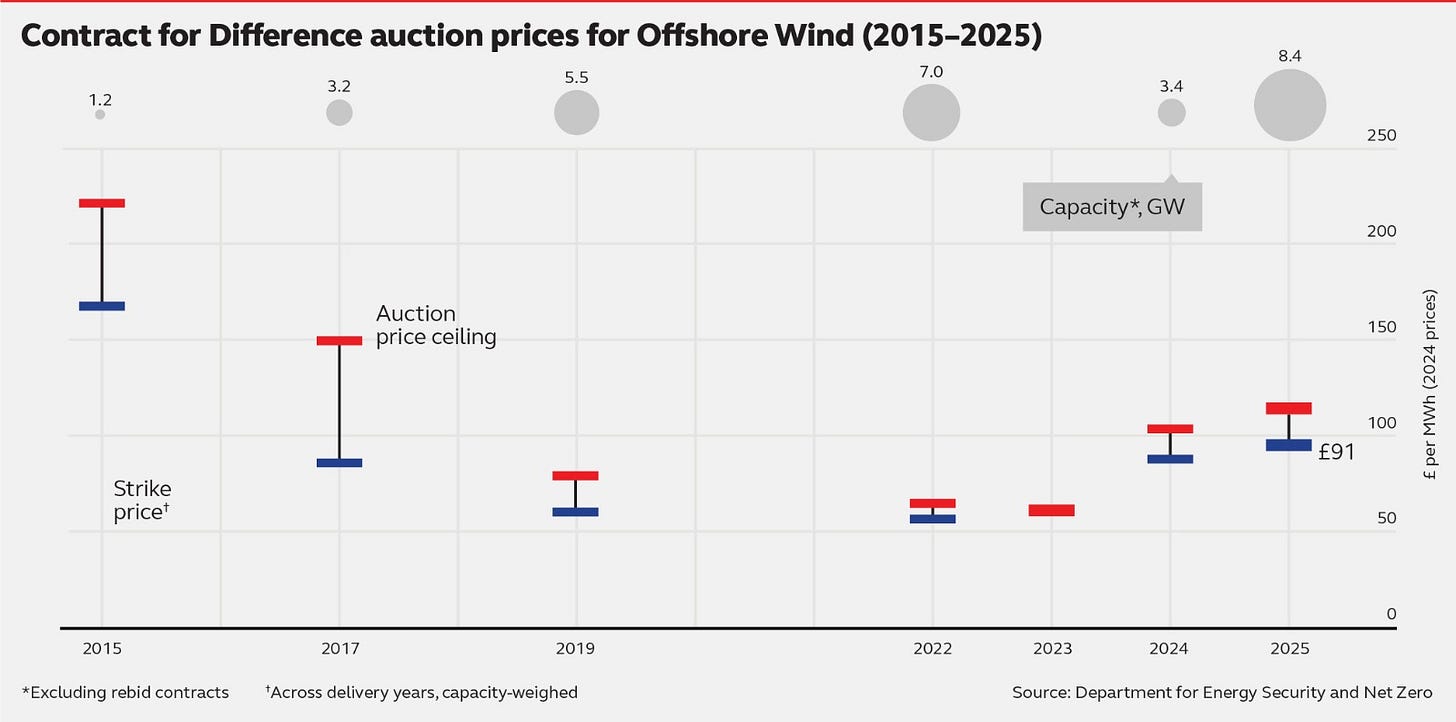

Britain just bought 8.4GW of new wind capacity. They will now go ahead backed by 20-years contracts guaranteeing them a fixed-price of £91.20 per MWh (in 2024 prices).

Britain’s electricity prices are the highest in the developed world (or at least, in the top three accounting for subsidies), yet the weekly average wholesale price of electricity is currently £75-80 (per MWh). And that price is, by recent standards, high.

Electricity pricing is really complicated. Working out the final impact on bills is tricky. Analysts at Aurora Research and Baringa claim that bills would go down, even if the auction cleared at £94 per MWh. That’s because although CfDs top up generators if the wholesale price is below the strike price, renewables still bid down the wholesale price the rest of the market clears at. And in their model, this latter impact outweighs the former.

Another recent study suggested that renewables are already lowering bills by a fair clip because while they may often be more expensive than the average wholesale price, they still knock some of the least efficient (most expensive) gas plants from the merit order.

It was this logic that prompted the Government to almost double the auction budget after bids came in a fair bit lower than the £114 maximum price.

Other analysts disagree. Independent energy analyst Ben James suggests that a strike price above £70 is likely to be at best neutral (and above £80 bill increasing). Part of the issue is that the more optimistic models only look at part of the costs.

They fail to account for the fact that wind is often constrained by a lack of grid capacity. If the new wind (most of the new capacity is wind) is behind transmission constraints, then wind generators will actually be paid to switch off. One way to loosen those constraints is to invest in new transmission infrastructure. That costs money, but those costs aren’t accounted for by the model.

There are other problems too.

Wind generation is highly correlated. When it’s windy in one part of the country, it’s probably windy in another. The new generation will cut wholesale costs primarily when wholesale costs are very low (and in some cases) negative.

And there’s knock-on impacts for gas. If lower wholesale prices mean gas plants run for even less time than they currently do then gas generators are likely to require bigger capacity market payments to compensate.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that when all the costs are factored in, the deals struck today will push bills up at a time they are already high.

In the minds of most British voters, Labour were elected on a pledge to slash annual energy bills by £300. And just like their pledge to build 1.5 million new homes, most independent experts expect them to fail. There were some steps in the right direction at the Budget. Some policy costs (charges on bills to pay for things like home insulation and historic investments in renewables) were taken off bills, moved either on to general taxation or eliminated altogether (one insulation scheme has been scrapped).

This isn’t, however, the way voters were told bills would fall. High energy bills were blamed on Britain’s exposure to global gas prices. Labour would fix this with a dramatic dash for clean power by 2030. Gas would still be on grid as backup, but the hours in the day where gas set the price of power would fall dramatically.

When they made the pledge, renewables were ‘cheap’. The two auctions before Russia invaded Ukraine cleared at £55 and £52 respectively. When wholesale prices are higher than CfD prices, generators refund billpayers. In the months following the invasion, wholesale prices hit £511.20. Wholesale prices went above £100 in September 2021 before the invasion, and stayed above £100 and far beyond until December 2023 while the weighted average of CfD prices was £156/MWh. Bills were over £1bn lower as a result.

Like most things, renewables got more expensive after Russia’s invasion. No offshore wind projects bid below AR5’s £61 auction price ceiling and as a result, no new offshore wind was bought as a result. The last offshore wind auction did clear, but at a much higher price: £82.

Today’s auction price is £9 higher per MWh, but that understates the cost increase. In the past CfDs were offered for 15 year terms. In this auction the contract length was extended to 20 years of inflation-linked fixed prices. Before the auction, civil servants estimated that this would knock around 12% off the final price. When you account for this, the cost jump from AR6 to AR7 is more like 30%.

Put simply, it has got more expensive to build new offshore wind farms.

Why have renewable projects got more expensive?

Finance

Renewables are extremely capital intensive. For fossil fuel generation, the big driver of costs is fuel. By contrast, once a wind turbine or solar panel is installed, it costs very little (maintenance is still important) to generate power. It is the upfront construction cost that matters. Wind and solar projects are extremely sensitive to the cost of borrowing.

When interest rates are low, it is much cheaper to build. When they go up, project costs can jump. Ørsted, who recently cancelled the Hornsea 4 Offshore Windfarm, have seen their interest rates go up. In 2019 they were able to borrow in pounds at a 2.125% interest rate. By 2022 this had jumped to 5.375%. Using those interest rates the debt repayment cost for a 15 year term (the previous length of a CfD) has risen by 25%. In their modelling for this renewable auction, DESNZ estimated that projects need to generate a 8.5% rate of return to go ahead.

Supply Chains and Inputs

It’s not just borrowing however. Almost every bit of a wind turbine has become more expensive. One analysis suggests that financing costs aside, the cost of building 1MW of wind capacity has gone up by two-fifths.

Wind turbines are 90% steel. British and European steel prices jumped by more than two-thirds between 2019 and 2022. One big driver of that cost increase is the UK’s high industrial electricity costs. High electricity prices caused by high gas prices paradoxically can make it harder to get off gas. They’ve gone down since, but are still 60% higher than in February 2021. Other inputs such as the neodymium magnets used in turbines have jumped in cost by two-fifths.

Offshore wind in particular has been affected by a number of bottlenecks as supply tries to keep up with growing demand. Lead times for electrical equipment like HVDC stations and export cables have jumped. In some cases lead times have stretched longer than two years. For 400kv transformers lead times can be up to four years long. There’s also a big shortage of the specialist installation vessels that take wind turbine parts out to sea. Projects are constrained by a lack of capacity at ports too.

In the long-run investments in new factories and port upgrades should loosen the constraints significantly and reduce costs. This is one reason to think that buying lots of wind at high prices today is a bad idea.

Planning

Like with most things, Britain’s planning system makes it more expensive to build new wind and solar farms. Before 2020, no offshore wind farm had to pay compensation for bird nesting sites. Since 2020, almost every single one has. Dogger Bank South, which successfully bid into AR7, will be paying £170 million in mitigating its impacts on seabirds.

Offshore wind farms will also need to comply with new regulations to reduce underwater noise. Industry sources tell us that this will push up the cost of every future offshore wind project by up to £120M.

Another way the planning system increases costs is by reducing scale. One offshore wind project, East Anglia 1 North, was cut in size by 40% due to the risk it might kill 13 Red Throated Divers in the Outer Thames Special Protected Area (Outer Thames SPA). It should be noted that the population of red throated divers increased in the Outer Thames SPA (from 6,000 to 18,000) at a time when three other offshore wind farms were built.

Bigger wind farms have economies of scale. They can spread the fixed costs around things like design, planning and transmission over more capacity.

Planning delays can bite too. A number of projects off the coast of Norfolk were delayed for two years trying to design a legally compliant compensation package to offset seafloor impacts. Legal challenges can delay projects too. One wind farm was delayed for a year by legal challenges once planning permission was granted. On top of the higher financing costs (and construction inflation), there’s also the need to pay the Crown Estate for the seabed lease. All of these push costs up.

Are we at the limit of CfDs usefulness?

When CfDs were launched, offshore wind was very expensive. Building up a supply chain. learning from past projects, and innovation have meant costs have more than halved. It is more than possible costs that fall again when supply chain constraints relax and further planning reforms, such as the measures proposed by the Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce.

The role of CfDs has, however, changed. They were intended as a stop-gap. A way to support less mature (but desirable) technologies. As technologies matured, the expectation was that subsidies and support would be reduced and renewables would increasingly be ‘merchant’. That is to say, they would compete like any other technologies. Their role is much bigger now. More and more of the market will be set by long-term fixed price contracts.

This is a problem for a few reasons.

Competitive CfD auctions were effective at driving down renewable costs. If you want to double onshore wind, triple solar and quadruple offshore wind by 2030, as Labour promised, then CfDs are likely the best way you can procure that. But, increasingly the question isn’t just – “How can we buy the wind and solar we need as cheaply as possible?” – it is how much wind and solar we really want on the grid. We are stuck with the problems of central planning.

One of the key ways to bring down bills and decarbonise is by making more and more demand flexible. Heat pumps, batteries, and EVs can all reduce the strain on the grid and save consumers money by shifting demand to when wind and sun are abundant. Likewise grid-scale batteries can eat up demand when power is cheap and plentiful and release it when it isn’t. Yet flexibility only works if there are strong price signals. If the wholesale price is increasingly irrelevant, because generators are paid a fixed-price, then there’s little incentive to invest in flexibility.

More than anything Britain needs cheaper power. To save jobs and industry, we need to bring down industrial power prices. To get emissions down, we need it to be attractive to switch to electrify heating, transport and just about everything else. The deals struck today don’t do that.

The shift from 15-20 years in CFD tenor requires an adjustment as Sam says - by approximately 12%. On that basis, the real cost in 2024 money is £101.92 per MWh. And this does not, of course, reflect the full cost as consumers will continue to need to retain lots of gas back up remunerated to stand idle, to plumb in more expensive electricity connections to remote generating sites, and pay more balancing costs and constraint payments. The idea of CFDs - as Sam points out - was to ease this "sunrise"offshore wind technology towards commercial viability. We are now more than a decade in and have now seen costs rise over the two most recent auction rounds, during which time power prices for offshore wind have doubled from the 2022 round, and now stand at a roughly 40% per cent premium to current wholesale prices - even accounting for discriminatory carbon costs and high gas costs. Moreover these high prices are locked in for 20 years. It's a disaster for the UK, where - as everyone can now see - industry is shutting down left right and centre due to excessive energy costs. Yet the government will doubtless try to spin this as some sort of triumph..

Interesting piece Sam, it misses one key point for me, which is what the cost of building the alternative fossil fuel energy generation asset would be at today's (or 2024) prices. The most efficient form of fossil fuel generation is of course CCGT and the price that would electricity at is £147/MWH. That makes today's £91/MWH extremely attractive and indeed 38% lower than Gas. I make this and broader points in this piece