How bad regulations accumulate

Will relaxing child-to-staff ratios, making MoT tests less frequent, and cutting tariffs on mangoes and oranges solve the Cost of Living Crisis? No, but there’s still good reasons to do it anyway.

The news that the PM has asked his Cabinet to identify non-fiscal (i.e. free) reforms that will reduce the cost of living has been greeted with derision. On the one hand, it is fair enough to point out that the package of measures will be insufficient to protect those struggling to keep their heads above water due to rising fuel and energy costs. Uprating benefits in line with inflation would do more and should be the priority.

But governments can do more than one thing at a time, and the cost of living crisis is a problem for everyone, not just those on benefits. Identifying regulations which push up prices and provide little benefit in return is an eminently sensible approach. Here’s three reasons why I suspect we’ll find a lot more regulatory deadweight if we look for it.

CBA to CBA

Over the past few decades, serious efforts have been made to improve the quality of regulatory decision-making in the UK. Measures such as the adoption of the Better Regulation Framework (which states that regulations must be proportional, accountable, consistent, transparent, and targeted), requirements to publish regulatory impact assessments, and countless government reviews should mean that when new regulations are introduced they must have cleared a high bar. Sadly, that typically isn’t the case.

Regulatory impact assessments often underestimate costs. Take Theresa May’s reforms to the sponsorship of international students. A National Audit Office report found that the Government grossly underestimated the impact on sponsors (i.e. educational institutions). (via Martin Stanley’s fantastic website on regulation)

“The Department estimated the net direct cost to education providers (costs less benefits) of changes to Tier 4 was £25.5 million a year. We found the Department underestimated the financial impact on sponsors in the following ways:

The Department included a one-off cost of £25 per sponsor for familiarising themselves with the new rules. Sponsors told us that the true cost was at least £500 for staff to read the guidance and more if the cost of attending training seminars was taken into account.

The assessment did not include the cost of applying for educational oversight and meeting the inspectorates' standards. The application cost for this varies, depending on the size and sector of the institution, from around £9,000 to £20,000 in the first year. Implementation costs can add a further £10,000.

The cost of the additional administrative work arising from new requirements was not included, such as checking English language test results, monitoring performance against Highly Trusted Sponsor standards, evidencing attendance and communicating rules to staff and students.

The Department also assumed that colleges that lost their sponsor licence would be able to replace four out of five non-EEA students with domestic and European students. Private colleges and English language schools told us that there is little domestic and European Union market for the courses they offer. We estimate the extra regulation placed on colleges could result in an additional £40 million direct cost to sponsors.

…

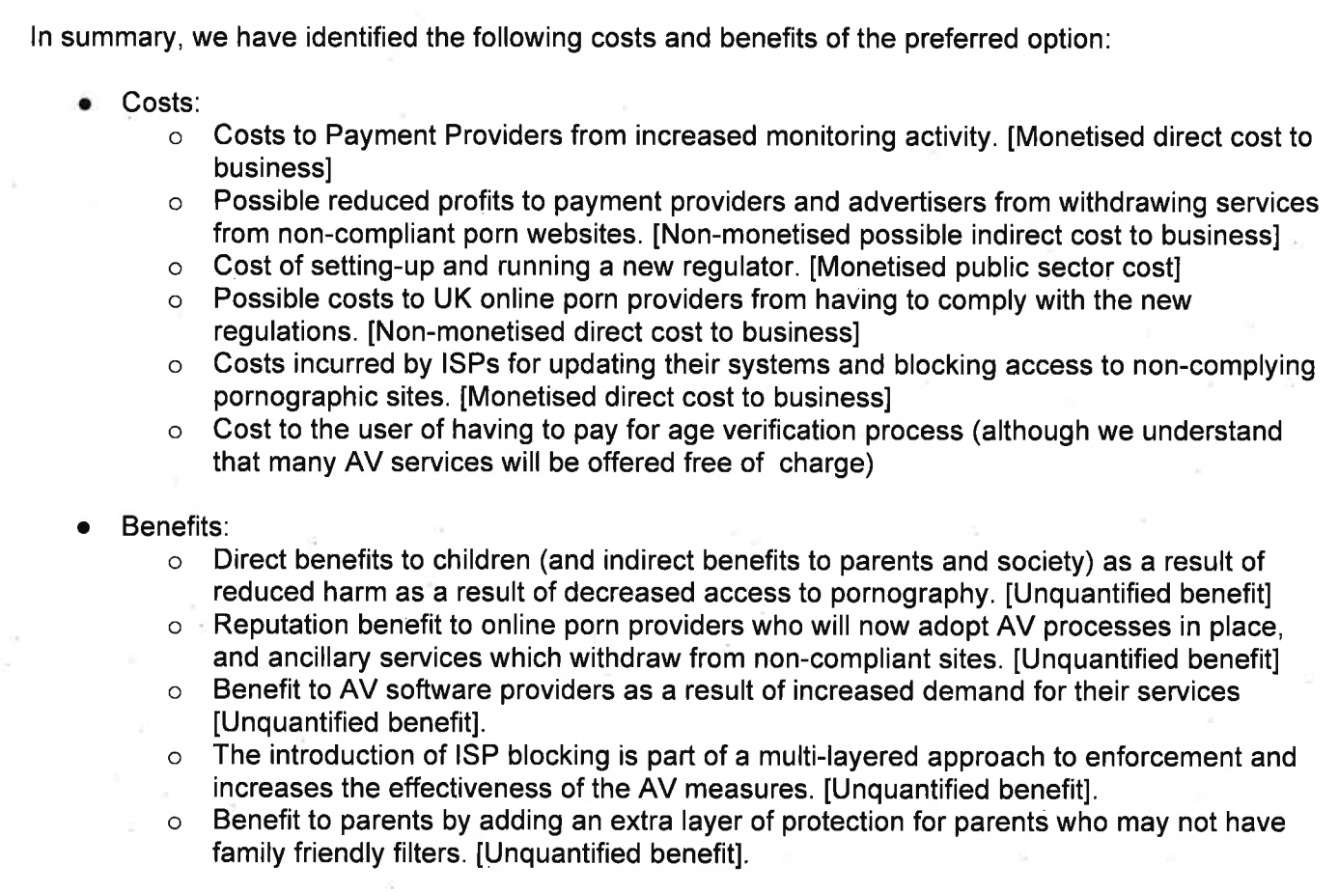

When impact assessments deliver politically inconvenient results for the government, they can include vague ‘unquantified benefits’ to put their thumb on the scale. Take the Government’s efforts to require age verification for all websites that host adult content, where every single benefit was unquantified:

Still, at least they’re trying to weigh up the costs and benefits of a regulation. Past regulations did not receive this luxury.

Scale insensitivity:

People are, typically speaking, insensitive to scale. If you ask the British public what’s the best way to cut carbon emissions, they will often mention things like using less plastic, even though this is around a hundred times less important than reducing car or aircraft travel

Likewise, the vast majority of car accidents are not due to mechanical failure, as our regulations might suggest, but due to driver error. Only a small fraction (~2%) are the result of mechanical failure and this is essentially consistent across nations. The relative rarity of mechanical failure as a cause of accidents may explain why US states that abolished MoT-style vehicle safety tests did not then see road deaths increase relative to other states.

But more intrusive and visible solutions tend to be seen as more impactful, even when they’re not. This is inefficient and mildly irritating in the case of MoTs and bans on plastic straws, but it can also be deadly. Coronavirus is an airborne disease, but the British public believed as recently as August that washing their hands was more effective at reducing the spread of the disease than ventilation and masking.

To be clear, this isn’t an anti-regulation point. Rather, it is about how we tend to get the wrong regulation. In the case of road safety for example, regulation on safety features, such as sensors that tell you when your brakes are faulty, are a key driver of why mechanical failures are so rare.

Bureaucratic inertia:

One reason why bad regulations remain on the books is that assembling the information needed to assess their effectiveness is costly. On top of that, taking on interest groups who benefit from ineffective regulations and persuading others of the benefits typically carries its own political cost. Eliminating restrictions on supply without creating winners and losers is possible, but it typically requires a fair bit of thought. Take an idea like street votes, which turns suburban intensification into a win-win for people who would currently be opposed. Anticipating potential objections, building a coalition of support, and drafting legislation is a long slog. For a problem as big as the housing shortage, it is time well spent for policymakers. It probably isn’t for smaller issues like the frequency of MoTs.

In the case of the MoT, it was brought in when accidents caused by mechanical failure was a much bigger problem. Most cars on the road were old, and many safety-enhancing innovations were yet to be invented. It seems fairly plausible that annual safety tests then did lead to fewer accidents and road deaths. The problem is that as manufacturers have made cars safer, the usefulness of the MoT has fallen.

You see similar problems pop up in all sorts of places. Take the rise of ridesharing apps like Uber, where previously regulations mandating ‘The Knowledge’ made sense, technologies like GPS and reputation systems have rendered them unnecessary. Technology changes fast, but regulation doesn’t always catch up.

Bad rules and regulations are more common than you think. Although the worst offenders eventually prompt action, it’s the costly (but not too costly) rules that accumulate over time that kill an economy by sclerosis