How to densify Britain's cities

Labour's plans need to go further

I recently attended a conference in California where YIMBYs were celebrating a major legislative win. SB79 allows developers to build up to 9 storeys high on busy transport corridors. Cities like Berkeley – the place that effectively invented American NIMBYism – would no longer be able to block new mid-rise housing in well-connected locations. After a decade-long political battle, America’s worst housing shortage is on the verge of being solved.

We know that SB79 is likely to be transformative because across the world similar legislation has had a massive impact on affordability. In New Zealand, the city of Auckland’s planning rules were reformed to allow the same – dense development near transport by-right – and researchers found it kept rents 30% lower than the counterfactual. Under Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand rolled the same policy out nationwide and has seen a construction boom. And New Zealand’s new Housing Minister Chris Bishop is taking the policy even further and removing anti-supply red tape.

Unlike the above cases, and indeed much of Europe, Britain’s housing system is not ‘rules-band’. Planners and planning committees are given huge discretion to approve or reject individual schemes. Winning approval, even in areas specifically identified as ‘Opportunity Areas’ for housing, can be extremely taxing. A fourteen-flat development in Walthamstow, less than 10 minutes walk from the Victoria Line, required a 1,250 page planning application. Its developers produced more than 70 separate documents and still have waited over a year for a decision from the local authority. This isn’t just a Walthamstow problem either. One SME housebuilder recently revealed that Croydon required them to produce over forty separate validation documents to get planning permission. In the PM’s backyard, Camden, a major brownfield development was delayed because planners were not satisfied that the project was ‘exemplary’ in terms of ‘the circular economy and whole life carbon impacts’. In Cambridge, one of the most unaffordable parts of Britain, all new developments (10 units or more) must spend at least 1 per cent of their capital costs on public art.

Part of the problem is that every local authority has the ability to set its own ‘development management policies’. In some areas of policy, it is a case of pure inefficiency. We simply do not need every single local authority to have its own special policy on flooding. General principles that apply to every area should be sufficient (and are more likely to be formed by genuine expertise).

In others, development management policies are an opportunity to block development by the backdoor. For example, London boroughs tend to have much stricter policies around embedded carbon and energy efficiency. The result is that developments that might otherwise be accepted are rejected because they do not meet the high environmental standards that some boroughs insist on. The result is self-defeating on carbon grounds. London’s fantastic public transport network means that Londoners tend to have much smaller carbon footprints than people in less-dense areas with worse transport links. So every home blocked on carbon grounds will push people out of London and into more car-dependent parts of the country.

In theory, the Government could change this. The Levelling Up and Regeneration Act contained the power to create National Development Management Policies (NDMPs). In effect, MHCLG could declare standards for embedded carbon, flood protection, and access to light that supersede any local policies. In other words, it doesn’t matter if Camden thinks you aren’t ‘exemplary on whole life carbon impacts’ so long as you meet the national standards they can’t reject your planning application on those grounds.

Yet it appears NDMPs will be much weaker than intended. At the Housing, Communities, and Local Government Select Committee, Reed told MPs that he will not enact S.93 of LURA, which would give NDMPs the same weight as each and every local plan. Instead, NDMPs are set to be non-statutory ‘material considerations’. In other words, councils should take them into account but could still ignore them if they think they have compelling reasons to do otherwise. In this form, they are less likely to cut through bureaucracy and more likely to add to it. Planning lawyers will be paid good money to argue before the Planning Inspectorate over whether or not NDMPs trump local considerations. What a waste.

This is a problem for potentially the most powerful pro-growth idea that Labour have put forward in Government: the Brownfield Passport. Chancellor Rachel Reeves recently announced that the Government would soon be consulting (she stressed it’d be “a quick consultation”) on making ‘Yes’ the default answer for new denser housing on previously developed land. If it is put in place, projects that conform to design codes and meet certain density standards can only be rejected in special circumstances.

This is the idea at least. NDMPs would be the logical tool to make this a reality, yet if they lack statutory footing they risk under-delivering. There’s precedent here.

In 2020, the last Government announced a radical planning reform. It gave homeowners the right to extend their property upwards by 3.5m. While there were carveouts – it didn’t apply to buildings built before 1948 – the Department (then DLUHC) believed it would unlock something like 78,000 homes. Yet the policy flopped because councils still were able to reject extensions on narrow grounds relating to impacts on adjoining properties.

The first attempt to extend a bungalow upwards was rejected. The courts sided with the NIMBY council. Further attempts also failed. In each court case, grounds for rejection expanded. By the time the courts were done with it, the definition of ‘adjoining’ extended to ‘the surrounding area’. Councils were given carte blanche to block people from exercising their right to extend upwards.

When Labour took power, they updated the National Planning Policy Framework to allow upward extensions and did not include the same carveouts that the last Government did. This is a radical move, in theory, but has not led to a wave of upward extensions so far. One issue is that the change is so wide-ranging that planning inspectors appear likely to interpret it as ‘you should approve this extension unless there’s a good reason’. The problem is councils are quite good at finding ‘good’ reasons to say no. For example, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and most local plans also give strong weight to heritage concerns. As it is only a material consideration, this new right to extend is likely to be much less radical than intended.

Curiously, a previous policy on upward extensions focused solely on allowing mansard extensions under specific conditions: that they emulate the style of mansards in the area at the time of the building’s construction and is consistent with the prevailing street scene. Some planners (including I am told planners within the Housing Ministry itself) commented that the policy was peculiarly specific. This was deliberate: the wording was designed to give as little discretion to local blockers as possible. We will never know the full effect of this policy as Labour expanded it when they came to power, but the case law that emerged suggested the policy had ‘real teeth’.

The lesson is that unless NDMPs are given statutory footing – which the Government still can do – they will require extremely careful drafting to have their intended effects. It will be hard for a broad ‘automatic Yes’ for brownfield development to have a big impact under these conditions.

There is an alternative, however. If the Government is unwilling to use the powers created by LURA, they could still replicate their impacts via another route. In a paper prepared for the Land Development and Property Federation, planning experts Lichfields set out the NPPF could be reformed to give the Brownfield Passport real teeth (and give councils little wriggle room to block the sorts of development that the Brownfield Passport is meant to enable.)

The proposal – like all aspects – of planning law is complicated but here’s a simplified version.

First, any local plan deemed inadequate or out-of-date (e.g. prepared before the most recent NPPF update) would be subject to a much stronger presumption in favour of development.

Second, this new presumption is worded in a way that would make it extremely difficult to reject development deemed ‘acceptable in principle’.

Third, development is acceptable in principle provided it complies with standards around things like density and height set in a relevant NDMP.

Fourth, a new ‘Effective Decision Making’ principle would be added to NPPF. They describe this as a ‘barnacles off the boat’ policy. In essence, it would block councils from insisting on unnecessary assessments. Without it, councils could still insist on the forty or so assessments that have delayed new developments in places like Croydon and Walthamstow.

This package would solve another problem: what I call the London loophole. In theory, local plans should be updated every five years and be written with the latest NPPF in mind. But there’s a catch, if you sit underneath a strategic planning authority as London boroughs then your housing targets and policies have to sit in line with that authority’s spatial development strategy. In the case of London that’s the London Plan 2021. Any plan put forward currently will have the London Plan 2021’s lower housing targets and not the higher targets in the NPPF until the London Plan is updated. If a borough puts forward a plan now with these lower targets, they don’t have to update their plan for another five years. Higher housing targets won’t bite in some boroughs for years. NIMBY councils that want to avoid the higher targets appear to be putting in their local plans early to lock-in lower targets for another five years. This is a slightly moot point however, London is building so few homes at the moment that even 2021’s lower housing targets are still out of reach.

What should be in the Brownfield Passport

Labour should be bold and look to replicate the approach of New Zealand and California. For land within walking distance of railways stations or town centres, developments of six-storey (plus a mansard) or under should be considered acceptable in principle. For land adjacent to or within five minutes walk from a train station/town centre, taller developments up to eight storeys should be classed as ‘acceptable in principle’.

The Brownfield Passport should be targeted. It should only apply (or at least only apply in its strongest form) to places with clear affordability problems, where house prices are 7.5 times local incomes. It should also include clear safeguards for the environment with a requirement of no net loss of green space.

Councils should also be allowed to opt out certain neighbourhoods from the policy, if they can make up (and then some) the potential lost housing by creating even more liberal Local Development Orders (planning rules where certain specified developments are allowed automatically) in other qualifying areas. When the controversial Medium Density Residential Standard, which automatically allowed four-storey development in large parts of New Zealand’s cities, faced a political backlash, the National-ACT Government’s solution was to allow opt-outs for specific areas if housing targets could be exceeded by other means.

In Houston, opt-outs for a major upzoning were allowed when entire streets petitioned to restrict development via a covenant. This meant that while the upzoning only ended up applying to just over two-thirds of streets, the policy was able to pass with much less opposition than such a radical policy would usually face.

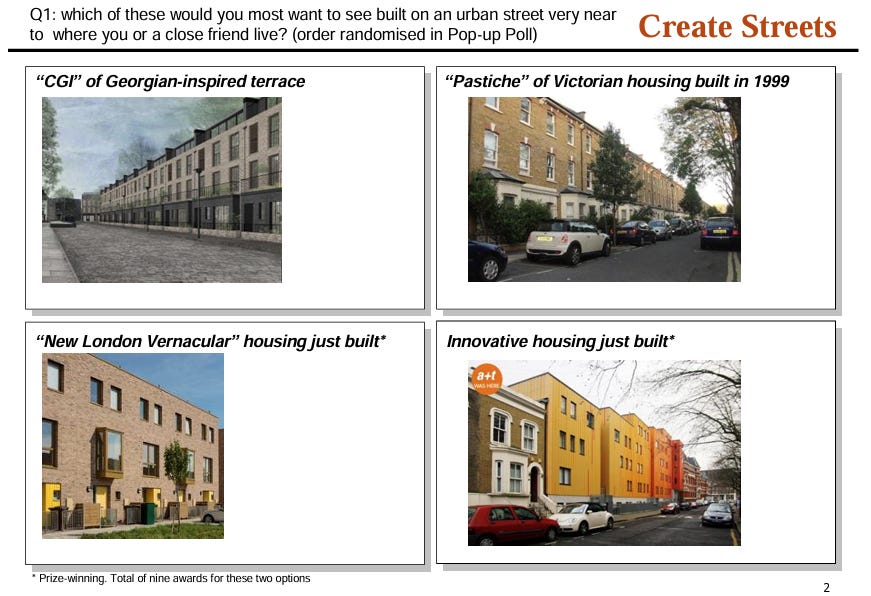

Crucially, while local authorities should have less of an ability to block densification in general, they should however be able to insist that new developments fit in by setting clear design codes. It is important, however, that these design codes are developed using easy-to-understand visual preference surveys. Research shows there is a ‘design disconnect’ between architects, planners and the rest of us.

When people were surveyed the top two options were preferred by an overwhelming margin. Create Streets, however, notes that the bottom two images have been awarded at least nine separate architectural and planning prizes. The most popular option – Victorian Pastiche – has not received a single prize. There’s a much better chance of the public accepting a relatively radical shift in planning policy if what’s built is their idea of an attractive building.

This could have a massive impact. Britain Remade have calculated that it is possible to build an extra 134,000 homes by merely reaching terraced house density within walking distance of just 25 of London’s tube and train stations. This is without touching an inch of Green Belt.

Smaller is faster

Uncertainty squeezes out smaller builders. If planning permission for a new Barratt estate is refused, it is a problem for the developer (Britain’s largest) but it is not existential. They are able to spread the risk of rejection or delay across numerous projects. The complexity of planning also works against smaller companies. Big firms can spread those costs across dozens of projects, little ones can’t.

This is a problem – particularly at a time when housebuilding rates have dropped – because small builders tend to build out their planning permissions at a much faster pace.

So, why do SMEs build faster?

First, SMEs typically have much higher financing costs than bigger developers. As a result, they want to pay back their investment as fast as possible. As a result, SMEs are likely to bring properties to the market that could likely sell for more if they were held back for longer.

Second, large developers tend to build bigger projects. This can involve a lot more upfront work, such as building new roads or GP surgeries, which slows things down.

Third, when a big new estate or tower is finished, developers do not want to put every single home on the market at once. This would overwhelm the local market. Instead, they try to match the rate of sales to avoid a sudden (and temporary) drop in prices. This incentive isn’t there, or is at least weaker, for the smaller projects that SME developers build.

This is why the Brownfield Passport and NDMPs are so important. Not only do they encourage the densification of our most productive places and eliminate red-tape, they also shift development to the types of projects that can be delivered fastest.

Labour are on course to miss their 1.5m home target by over half a million homes. If they are to have any chance of meeting it, then it will be down to policies like the Brownfield Passport that get small builders building.

The community facilities that come with larger projects are also really important to avoid widespread local opposition from what I might call MIMBYs.

The GPs surgery’s etc really matter.

We are also going to struggle to overcome MIMBY opposition when projects are badly run and there is no consultation. When they wanted to build the Oxford-Cambridge expressway they refused to speak to the affected local villages even though they would have benefited from the project.

Yes you do have to speak to the rich, community spirited older people when you want to do stuff. I am sure Isembard Kingdom Brunel did and carefully explained to them that they would be able to get to London for a day trip.

"Labour are on course to miss their 1.5m home target by over half a million homes. If they are to have any chance of meeting it, then it will be down to policies like the Brownfield Passport that get small builders building."

They will not meet it, they won't do half of their target. I don't particularly blame Angela Raynor who I think is sincere in her ambition and commitment in this respect. The government is not ready to grasp the nettle, indeed does not even recognise the scale of the problems involved. The Conservatives were just as bad. Gove made matters worse as did most of his predecessors.

We are buried in a quagmire of regulation and quangos and it will take radical surgery to resolve this.