How to make nuclear cheaper in Britain

My speech on Britain Remade's Policy Playbook for Cheaper Nuclear

Today, Britain Remade publishes A Policy Playbook for Cheaper Nuclear. Backed by industry, a former Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, a former Nuclear Minister, and the co-chair of Labour’s Growth Group Chris Curtis MP. This report sets out a radical, but practical plan to cut the UK’s absurdly high nuclear build costs. Every recommendation was reviewed by a team of experts on radiation, nuclear engineering, and actually delivering complex nuclear projects. You can read it here.

Below is a lightly edited version of a speech I gave at the launch today in Westminster.

If Britain wants lower bills, clean power, and the energy to fuel AI and industry, we have to make nuclear cheaper and faster to build.

Yesterday brought some good news. US firms want to build here: X‑energy and Centrica are planning twelve advanced modular reactors at Hartlepool; Holtec with EDF and Tritax looking at nuclear‑powered data centres in Nottinghamshire; and Last Energy partnering with DP World to electrify London Gateway port with low carbon nuclear.

The interest is real. Turning it into shovels in the ground and data centres online, on time and on budget, depends on making the UK a lower‑cost, faster‑to‑build place. That’s what this playbook is for.

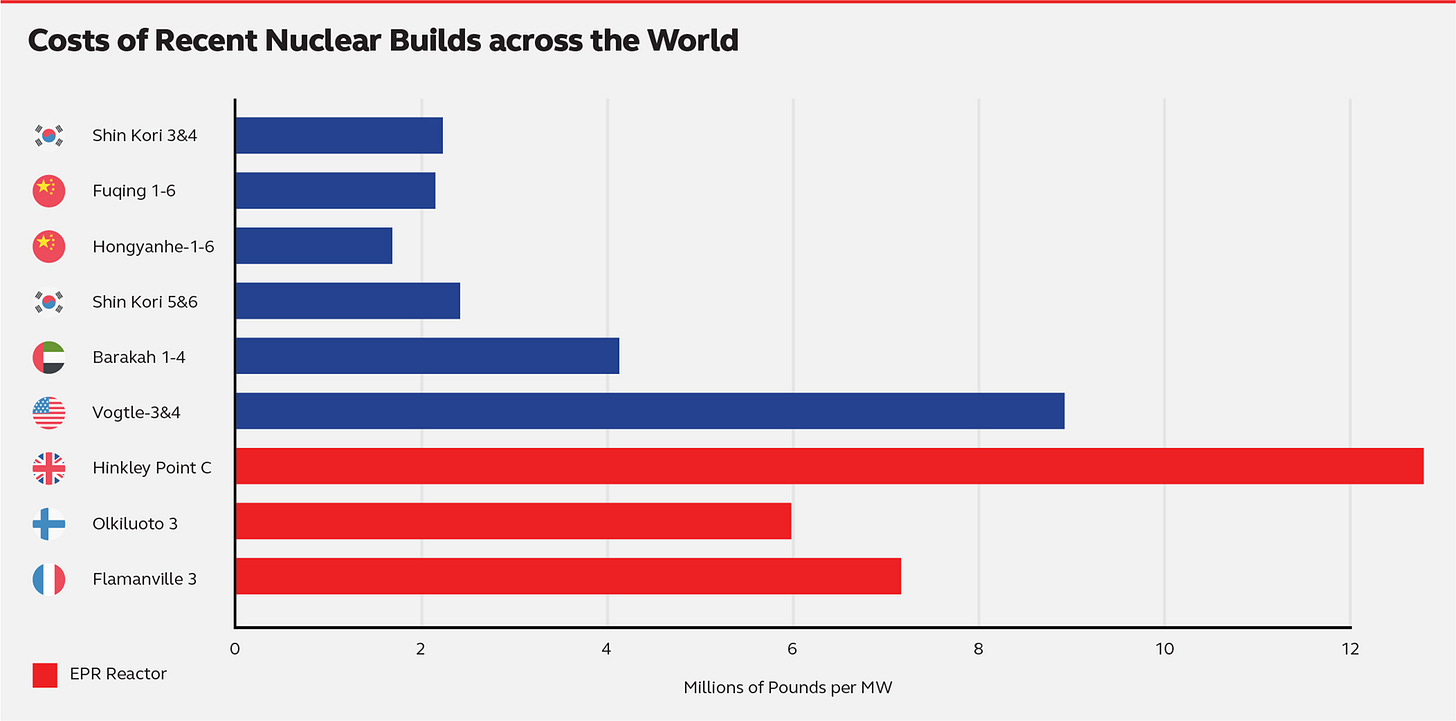

Right now we aren’t that place. Britain is the most expensive country in the world to build new nuclear. Hinkley Point C is set to cost £46 billion — that’s £14,100 per kilowatt of capacity — making it the most expensive nuclear project built anywhere ever. Britain Remade reviewed every nuclear project built since 2000: no one else comes close.

France and Finland are delivering the same EPR design for about half as much per kilowatt; South Korea builds at around one‑sixth of our cost.

And we’ve gone backwards: Sizewell B, finished in 1995, cost about £6,200 per kilowatt. Sizewell C’s budget is more than double that before accounting for any overruns.

(Thanks to Archie Hall for letting us use his brilliant, but worrying graph)

Why does this matter? Britain can’t end its dependence on gas with renewables alone. We should be proud of the progress we've made: since 2010 we’ve added roughly 40 GW of wind and solar, with more to come.

But as renewables take a larger share, intermittency costs bite — balancing the grid, curtailment, backup for the weeks when it’s calm, and overbuild to ride out long winter lulls.

Those costs add up, and there are still gaps that require firm, always‑available power.

AI changes the game. Data centres are always‑on. They want clean baseload 24/7. The Government is targeting 6 GW of AI‑ready capacity by 2030 and 11 GW by 2035. Wind and solar have many strengths, but they’re not designed to meet non‑stop demand on their own without huge overbuild and storage.

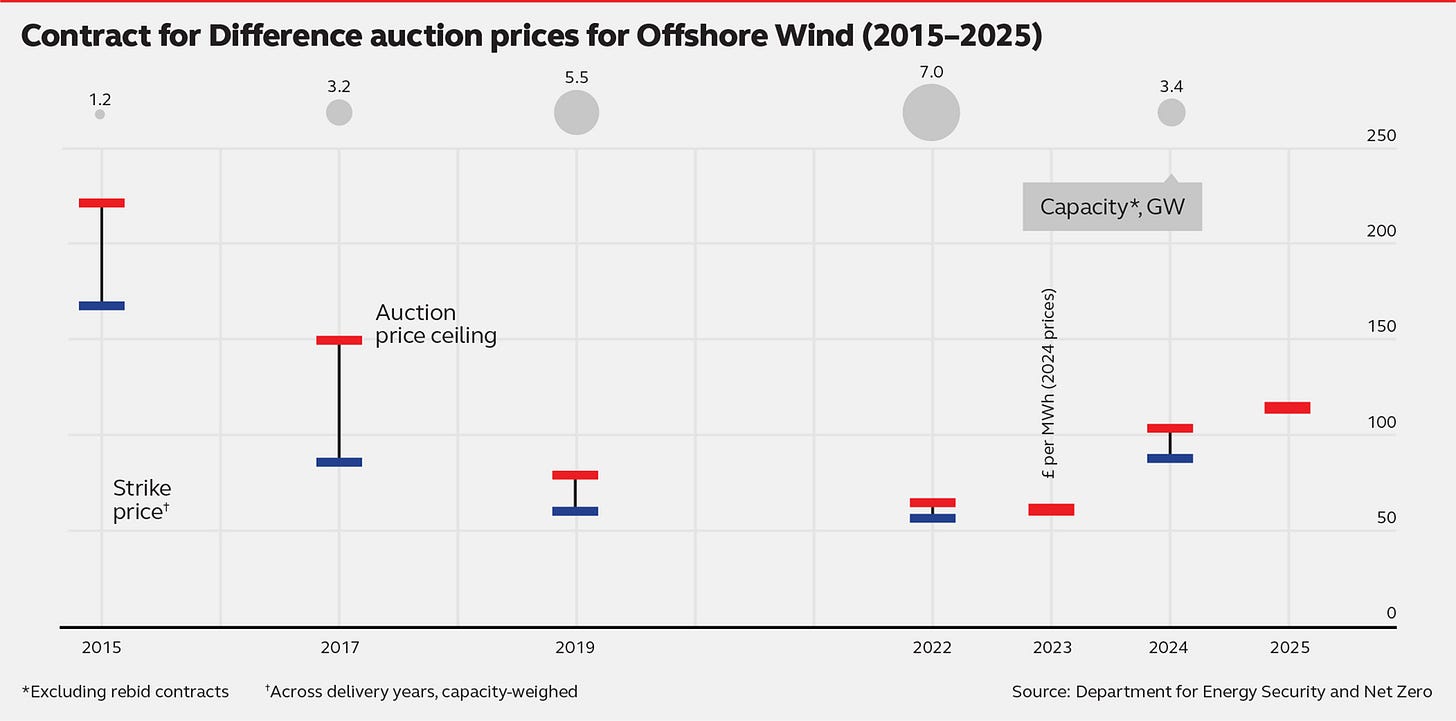

We’ve modelled this using the Government’s own Future Energy Scenarios. The message is straightforward. At Hinkley’s current cost, building another large plant after Sizewell C would raise bills — by about £6 per household — even if renewables end up a bit pricier than expected. And we can see the trajectory of renewables isn’t one big decline. At least, not for offshore wind.

But at French or even Korean costs, bills fall. One large plant at those prices saves households billions over 25 years; and a fleet saves more. If renewables costs rise above the official baseline — which recent auctions suggest is possible — the case for more nuclear grows.

So why is it so expensive to build in Britain?

First, planning and permitting are slow and paperwork‑heavy. Sizewell C went through seven rounds of consultation. Hinkley’s environmental statement ran to 31,000 pages; Sizewell’s full stack was closer to 80,000. Even after consent, there were more than 160 permits. Time, uncertainty, cost — without necessarily better outcomes for nature.

Second, we over‑specify and gold‑plate. Hinkley had thousands of UK‑specific design changes, including a fish‑return system and an acoustic fish deterrent — the famous “fish disco”. These choices mean more concrete, steel, cabling, complexity and risk.

Third, we stopped building. With a thirty‑year gap, EDF had to rebuild supply chains almost from scratch; when construction began on Hinkley Point C, there was reportedly just one nuclear‑qualified welder left in the UK. Stop‑start pipelines mean firms don’t invest in skills and kit, our industry stays fragmented, and we rely on foreign suppliers and layers upon layers of subcontracting.

Fourth, we don’t standardise. France and Finland stuck closer to the core EPR design. We added extra layers — a separate hardwired control system, additional diesel backup, an extra spent‑fuel‑pool cooling train — choices that push costs up.

Then there’s the way we regulate.

Safety is essential. But we often try tp eliminate ever‑tinier risks at a very high cost. Britain regulates radiation on the “as low as reasonably practicable” principle, or ALARP.

Sensible in theory; and in some sectors it works well. But, in practice for nuclear it drives bespoke features and long safety cases to avoid trivial doses of radiation.

Nuclear is already one of the safest ways to generate electricity — in the same league as wind and solar, far safer than fossil fuels.

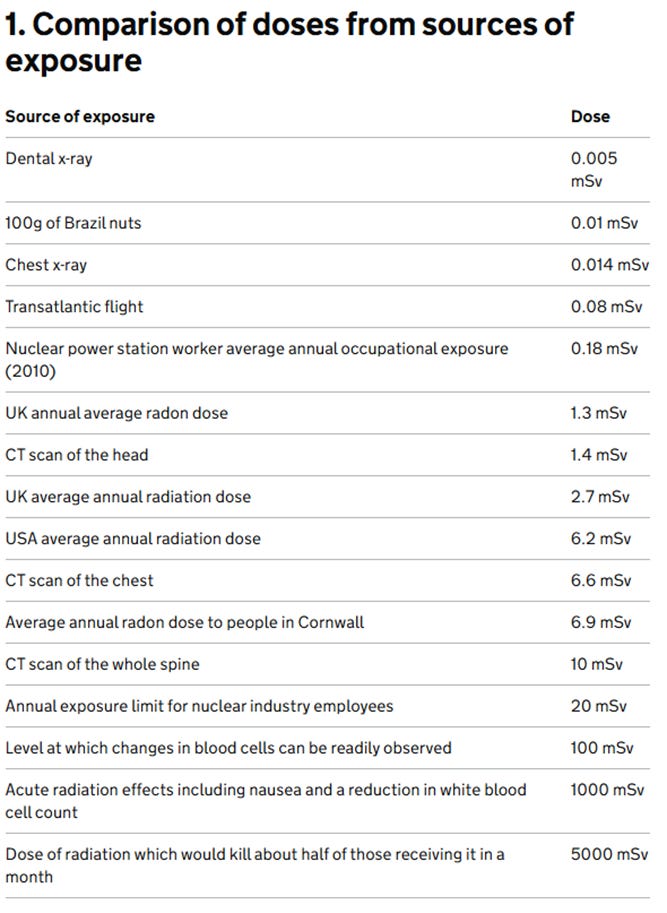

Radiation is a scary word, but almost all the radiation we recieve is ‘natural’. In fact, the average Brit gets a couple of millisieverts a year from background radiation from rocks in the earth and cosmic rays; in Cornwall it’s nearer seven.

Around Hinkley Point B the highest‑exposed person gets a few hundredths of a millisievert a year — roughly a brief weekend in Cornwall or a handful of Brazil nuts.

Modern designs have layers of passive safety; even in the worst‑case scenarios the public will only be exposed to a tiny dose. Far below, what they’d receive from background radiation.

Planning law adds friction. We mandate long seasonal ecological surveys, require site‑specific mitigations that are expensive to maintain, and give opponents multiple bites in the courts.

Across Hinkley and Sizewell there have been seven legal challenges in recent years, delaying work by more than four years. Even where challenges fail, they embed caution and drive delay.

All this makes sensible late‑stage improvements harder. Hinkley’s proposed switch from a wet to a dry spent‑fuel store — a change many operators have made because it’s easier to run — meant a fresh environmental permit and a planning variation because the building would be slightly longer.

If every sensible change risks reopening permissions, we deter innovation.

It also hurts the economics of fleets and SMRs. Long, costly processes are a fixed overhead. The whole point of a fleet is that you can spread upfront costs like design over multiple fleets.

So what do we do? Our playbook focuses on three things.

First: We need to restore proportionality to safety regulation

The Office for Nuclear Regulation should be given a clear objective to enable the safe deployment of civil nuclear power. As it stands, the ONR can meet its brief without a single nuclear plant being hooked up to the grid.

It also means accepting safety analyses from trusted peer regulators by default, and only adding UK‑specific work where there is a clear, evidence‑based need. The deal we’ve struck with the US should be expanded and go further.

ALARP decisions can be challenged on grounds of gross disproportionately, but cost-benefit analyses are almost never used. One problem is there's no standard value for what saving a life or preventing exposure to one unit of radiation is worth. We have that for the NHS, every other safety feature, and the US has it for nuclear. Nuclear in Britain flies blind making challenges harder and rarer.

We also need to reassess the levels of radiation we worry about. At the moment, we have a Basic Safety Objective that is set at absurdly low levels. The idea behind the Basic Safety Objective is that its the point below which it is not worth the time of regulators to scrutinise safety cases below it. Most plants operate below it (even older ones) but proving that you've got there is complicated and expensive. We need to accept that some exposure - say 1/10th of the radiation the average Brit is exposed to from natural sources is below the level worth worrying about. And for other higher exposures that are still below the legal limit for radiation exposure, let's flip the burden of proof. The ONR should have to prove changes are necessary, not the other way round.

And, we need to prioritise real‑world safe operation for at the top of the “relevant good practice” hierarchy. Proven designs shouldn’t be endlessly re‑engineered for Britain. Regulators should focus effort on material risks rather than chasing marginal theoretical reductions. If you read the report in full, there's a fascinating section based on the research of Cambridge's Alicia Durham on all of the changes the ONR forced upon the ABWR design when they tried to build one in Wales. In one case, they proposed a vent that would cut one 'banana's worth' of radiation from normal operation.

Second: We need to streamline planning and environmental permitting.

Right now the process is overloaded with duplication and delay. We should start by consolidating the long list of overlapping permits into a simpler, single process.

When it comes to environmental and habitats rules, we need to fix how the Habitats Regulations work. At the moment, projects often have to prove a negative — showing there will be no impact — which creates endless paperwork. The rules should be amended so that Natural England can only block a plan if there is clear scientific evidence of harm.

Small, trivial effects should not be treated as if they threaten the integrity of a site. And where compensation is needed, developers should be able to fund improvements that boost the wider network of protected sites or help meet the Environment Act targets nearby — not just narrow, like‑for‑like fixes on the project footprint. Once planning permission is granted, there should be no need to run a whole new Habitats assessment for every licence, permit, or condition.

We also need to remove vague duties, like the one in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act that requires projects to “further the objectives” of National Landscapes. That sort of open‑ended wording adds uncertainty without protecting nature more effectively.

Statutory consultees need to be held to the deadlines set for them. If they don’t reply on time, their silence should count as consent. Government should legislate for this “positive silence” rule so consultees cannot hold up projects indefinitely.

We should also cut back on repeat litigation. Once an issue has been properly tested at consent, it should not be endlessly re‑litigated through the courts. The current cost caps for challengers under Aarhus rules — £5,000 for individuals and £10,000 for groups — should be raised substantially, and lifted altogether for those who clearly have the means to pay or repeatedly bring weak cases.

And let's turn NIMBYs into YIMBYs. Councils should be allowed to keep the business rates from new nuclear and data centre projects in full. That way they share directly in the benefits, rather than only shouldering the burdens.

None of this lowers the bar on protection. It targets effort where it matters, cuts duplication, reduces perverse incentives, and removes delay that helps no one.

Third: unlock private investment, especially for SMRs and AI‑linked demand.

Small modular reactors are different: factory‑built modules assembled on a site no bigger than a football pitch, with lower unit costs and repeatability.

They can be financed privately through Contracts for Difference or long‑term power purchase agreements where data centres or factories buy their power directly from the plant.

We should make that possible. That means opening up government support schemes, like Contracts for Difference, to small modular reactors so they can compete on a level playing field. It means fixing the rules on clean‑power certificates and green finance so nuclear isn’t shut out of the “green” label, even though it’s as low‑carbon as wind or solar.

It also means sorting out the grid. Right now, getting a new grid connection can take a decade, and most of the queue is already taken up by wind and solar projects. We should make it easier for data centres or industrial sites that want to co‑locate with reliable nuclear generation to get a flexible connection, rather than waiting years in line.

If we don’t fix these problems, projects — and investment — will go elsewhere. The deals announced yesterday were announced on the premise that approvals would be streamlined.

Some will call this lowering standards. It isn’t. It’s being honest about risk: we obsess over micro‑risks in nuclear while tolerating bigger risks elsewhere. The result is higher bills for longer, slower decarbonisation, and a greater risk of energy insecurity and economic stagnation.

Britain led the world into the nuclear age — Calder Hall in 1956 and a dozen plants after. We can lead again.

The prize is big: lower bills, less exposure to gas shocks, a grid that can power heat pumps, industry and AI around the clock, and real progress on cutting carbon without swallowing huge areas of countryside.

Our message is simple. Nuclear works. It’s safe, clean and reliable. In other countries, it’s affordable too.

Britain can get there — if we change how we regulate, how we plan and how we finance. That’s what our playbook sets out: practical steps the government can take now to make nuclear cheaper, faster and easier to build,

If we want abundant, low‑carbon power, we have to build. Let’s get on with it.

You can read A Policy Playbook for Cheaper Nuclear online here. For a PDF, click here.

You made the statement "We added extra layers — a separate hardwired control system". I assume you are referring to the secondary reactor protection system?

If so, I believe you may, like others, be falling for EDF's propaganda. If you read the ONR's Design Assessment, the ONR required a separate secondary hardwired system, similar to the one provided for Olkiluoto 3. Hardly adding an extra layer, merely repeated a previously used design.

It should also be noted that the only other PWR in the UK (Sizewell B) also has an independent secondary protection system.

AI vs Non-AI Data Centers (Explained)

"From a power planning point of view, AI data centers are interruptible loads, they can be paused during peak demand, helping balance the electrical grid."

There are two main types of data centers: AI-focused and non-AI (traditional) ones.

AI Data Centers power things like ChatGPT or image generators. They use special chips like GPUs or TPUs. These are very fast at thinking, but don’t need to reply instantly. Like baking a cake, it takes time, and that’s okay. They’re often built in remote places near wind farms to save energy. If they shut down, they can just restart from where they left off. No battery or generator is needed, like pausing a Netflix download and resuming later.

Non-AI Data Centers handle things like banking apps or online shopping. These need to be fast and always on, users expect instant results. They must be close to internet exchanges.

Example: ChatGPT’s AI center can wait a few seconds. Your banking app? Can’t. It needs a low-latency, always-on setup.

See more https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhqoTku-HAA