I’m a skills sceptic, and maybe you are too.

Brits are less productive because it is too hard to build stuff.

Why is the average British worker less productive than their French, German, and American counterparts? And more importantly, how do we fix it?

To sum it up in a pithy line: Brits are less productive because it is too hard to build stuff.

Too hard to build new homes in our most productive places: Extensive restrictions on new development have left Britain with a 4.3 million home shortfall when compared to European countries. The shortage is most acute in London, Oxford and Cambridge with high rents removing the incentive for workers to move to the best paying jobs.

Too hard to build factories (and fill them with robots): Until recently, Britain’s tax treatment for investments in new equipment and machinery has been among the most punishing in the OECD. Between 2008 and 2018, the UK was the only (!) country in the OECD where investments into new industrial buildings did not qualify for capital allowances.

Too hard to build labs near our best research universities: Laboratory space in Oxford and Cambridge costs more than twice as much as it does in Amsterdam or even Paris. Laboratory space builders blame planning regulations.

Too hard to build new energy infrastructure like wind farms, grid connections, and nuclear power stations: To build a new offshore wind farm can take up to 13 years due to extensive planning bureaucracy. It has been 28 years since the UK last built a new nuclear power station.

Too hard (and expensive) to build new roads, railways and airports: The planning application for the Lower Thames Crossing (a tunnel between Essex and Kent) featured a 63,000 page environmental impact assessment. On a per-mile basis, HS2 is the world’s most expensive railway under construction costing more than twice as much as similar projects elsewhere.

Or as Labour’s Rachel Reeves recently put it: “Few of our economic ambitions - on growth, on jobs, on climate and on housing - can be achieved if we do not make it easier to build in Britain. Today, our planning system is a dead hand on the tiller of Britain’s ambition.”

What about skills?

There’s a common response to the ‘make it easier to build stuff’ theory of growth – “what about skills?”

In fact, if you read any column by a ‘serious’ economic commentator, you will find a reference to the “thorny problem of skills.” It is easy to see the appeal of skills-based explanations of the UK’s economic under-performance. Human capital, economists’ term for intelligence, talent, experience, and skills, is clearly a major factor in productivity and it is not a coincidence that the most productive parts of the UK are also the places where the graduate share of the population is highest.

Employers tend to agree too – at every business roundtable I’ve attended (and I’ve been to a lot) the topic comes up. And the Prime Minister’s signature growth policy is teaching every student some maths until they turn 18 to bring us in line with the rest of the developed world.

Now, education and skills are important policy areas with real scope for improvement, but I just don’t buy explanations of the UK’s economic under-performance that put skills shortages at the centre.

You could call me a “skills sceptic”. By that, I mean a few specific things.

Skills matter, but they are not one of the key constraints on economic growth in the UK.

The UK’s high levels of regional inequality are unlikely to be solved through education or training-based interventions.

The UK’s relatively low levels of productivity when compared to the US, France, and Germany are not explained by skills shortages or education levels.

At the margin, spending more money on stuff (roads, rail, nuclear power stations) is likely to yield a higher return compared to additional investment in education and training.

How could we tell if a lack of investment in education and training was holding back growth in the UK? I can think of a few things we might see.

In places where the share studying at university is low, new graduates can easily obtain suitable local graduate jobs.

Employers are willing to pay large premiums to hire university graduates and people with technical qualifications.

Lower levels of per pupil investment and worse student outcomes than other similar countries.

So what do we see?

Demand, not supply, explains why skill levels are highest in the most productive places

It is often taken for granted that because regions which employ more graduates are more productive, that increasing the number of graduates will necessarily improve productivity. But this confuses correlation and causation. It is equally plausible that more productive regions have more graduates because there are better job opportunities for graduates there.

If this alternative explanation is right then increasing graduate share while doing nothing to increase the demand for graduates will have little impact on productivity. Workers trained in the North and Midlands will either be underemployed or simply decide to take better-paying jobs in the South East, instead.

One way to detect whether or not a region has a graduate shortage would be to look at what people do when they graduate in that region. If the relatively few local people who do go to university easily find productive local graduate jobs, then it is a sign that education is the bottleneck. But, if when local people graduate they end up moving elsewhere to find graduate jobs or end up in jobs they are overqualified for, then it is a sign that the problem is a lack of demand, not supply.

So what does the data reveal?

A recent paper co-authored by MIT’s Anna Stansbury, Harvard’s Dan Turner and former Labour Shadow Chancellor/Strictly Come Dancing star Ed Balls find that graduate shares in the North East, North West, and Yorkshire stand out as particularly low, yet each region suffers from graduate drain. Stansbury, Turner and Balls find “the share of 27-year olds with degrees who live in each non-London region is lower than the share of 27-year olds with degrees who came from that region.”

It is hard to square this data with the skills shortage story. All things being equal, most people would prefer to live closer to their friends and family, so if a region is exporting graduates then it is a good sign that the problem is a lack of opportunities for graduates close to home, not a lack of graduates.

Wage premiums for skills are falling

Many things are important for growth, but not all are binding constraints. One way to detect whether a constraint is binding is by looking at prices. If employers are willing to pay a large premium to hire skilled workers, relative to workers who are less educated or trained, then it is a sign that the demand for skills is high relative to supply. And if the premium is growing then it is a sign that demand is growing faster than supply.

Stansbury, Turner, and Balls find that wage premiums for most degrees (except STEM) and vocational qualifications are falling.

In the 1990s, there were large graduate premiums across the board with graduates outside London typically earning 40% more than school leavers who only had A-Levels. Since then, there’s been a massive expansion in student numbers and a large fall (around 25%) in the size of the graduate premium.

Breaking the data down by degree type reveals more evidence of declining graduate premiums. Law, finance, and management (LFM) degrees were traditionally the most lucrative with graduates (outside London) benefitting from a 50-60% wage premium in the late 90s. This premium has fallen substantially to 35%-45% more recently.

STEM degrees have fared better with their wage premiums remaining stable outside London and rising in London. In fact, in many parts of the UK the STEM premium has outstripped the LFM premium. This is despite the number of people studying STEM subjects increasing over the same time period.

But while there is some evidence that a shortage of STEM graduates is a drag on growth, there’s no evidence of a general graduate shortage. In fact, for graduates who studied non-STEM, non-LFM subjects the graduate premium has collapsed to just 15%. The only place where a large graduate premium for such courses persists is in London - more on that to come.

Of course, skills policy isn’t just about university enrollment. Germany’s focus on vocational and technical education is often held up as a model for the UK to replicate, but the data suggests there’s no general shortage of workers with technical education either.

In every part of the UK, the wage premium for workers with non-university technical qualifications has declined by around 10 percentage points over the same period, despite the share of the workforce with such qualifications remaining relatively stable.

What are the implications of falling graduate wage premiums? It is important to think at the margin rather than over-indexing on averages. In the 90s, when the share of the population attending university was low and wage premiums for graduates were high, the UK was probably held back by skill shortages. Back then, an extra pound spent on education and training likely generated a good growth bang for your buck and I wouldn’t have put myself in the skills sceptic camp. In fact, I would probably have been calling for a big increase in spending on education and training.

But, the situation today is different. The low-hanging fruit has been picked and the return from training one additional worker is close to break-even for many types of courses.

British spending on education is high by international standards (and outcomes aren’t bad either)

Is Britain’s productivity stagnation a result of under-spending on education and training? Per-pupil spending may have fallen in real terms since 2010, but education spending remains high by international standards.

The UK spends slightly more per-pupil at primary and secondary level than Germany and France. At tertiary level (i.e. university), the UK spends nearly $10,000 per pupil more. In all three categories, the UK spends well above the OECD average.

At the employer level, the story is more complicated with the share of British workers receiving on-the-job training the second highest in Europe, but the number receiving on-the-job training lasting six days or more low (though still higher than Germany).

It’s not just spending either where the UK is close to the front of the pack. Educational outcomes in the UK aren’t bad either. The PISA rankings, which allow us to compare secondary education outcomes across countries, put the UK well above the OECD average for Maths, Reading, and Science. And just this month, an international study revealed that English primary pupils ‘are the best readers in the Western world… beating the United States and every other country which participated in Europe.”

What about tests of adult skill levels? Again, the UK seems to do alright. On the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills, the UK is well above the OECD average in literacy, exactly at the OECD average in numeracy, and above the OECD average in ‘problem solving in a technology-rich environment’.

Germany tends to do a bit better than us on numeracy and tech, but we beat the US and France in all categories. And when it comes to the percentage of adults scoring low on numeracy or literacy, Britain does well too. Having a lower number than France, the US, and the OECD average.

Skills are mobile, so attempts to ‘level up’ by training local workers are unlikely to succeed

There’s another implication to the fact that skilled workers are free to move. If you want to ‘level up’ a struggling town, investing in training and education is unlikely to pay off unless there’s an unmet demand for skilled workers. This isn’t to say training is a bad investment per se. More training may pay off for the individual, but if they take their skills elsewhere then you will do nothing to fix regional disparities. Something to consider for local leaders.

Attempts to level up would do better to focus on boosting the demand for skilled workers either by incentivising new businesses to set up shop or by building better transport links to gain agglomeration benefits.

Education involves economically wasteful signalling

Why do graduates earn a premium over workers who didn’t go to university?

In part, it is because they’ve acquired valuable skills that make them more employable. Studying law or medicine leads to high incomes because graduates pick up skills that are essential to their job. Beyond specifically vocational courses, degrees such as history or philosophy teach people how to analyse sources, structure arguments, and spot flaws in someone’s logic – all valuable skills in a modern service job.

But these clearly aren’t the only reason why graduates command a premium. Ability bias is another. To get into a top university in the first place you have to be smart. The sort of person who could get an offer from Cambridge will probably be more productive than the average worker even if they did not end up going.

And there’s another factor to consider – signalling. A graduate’s diploma communicates to employers that they are smart and diligent. To have passed difficult exams, engaged in independent study, and stuck with a course for three years tells employers that they are exactly the sort of person they are looking for. This matters because employers aren’t able to glean from a 30 minute interview how smart or hard-working an applicant is. Looking at their academic achievements is a useful shortcut for employers, but this comes at a cost.

Signalling can exhibit an arms-race dynamic. If everyone has a diploma, then not having one devalues a person in the eyes of an employer. This is a problem in fields such as journalism where learning-by-doing can trump formal education. In the past, many journalists went to work for a paper straight out of school, but now need a degree just to get their foot in the door.

To be clear, this isn’t to say that most or all of the premium that graduates command is down to ability bias or signalling. But, it is a reminder that graduate premiums are not just a reflection of the valuable skills people pick up at university, but other factors too.

Why physical infrastructure should take priority for now

In a much-mocked tweet, Sen Kirsten Gillbrand argued that the public’s perception of what is and isn’t infrastructure is too narrow.

“Paid leave is infrastructure. Child care is infrastructure. Caregiving is infrastructure.”

I believe something similar for skills. Our view of what is and isn’t skills policy is typically limited to training and education policy. It may, on occasion, stretch to immigration policy. But it should stretch further.

Take the case of London. I noted earlier that the only place in the UK where graduate premiums are high and persistent across the board is London. But, the reason London appears to suffer from a graduate shortage isn’t because it spends too little on skills or trains too few workers. It is because housing is too expensive.

Stansbury, Turner, and Balls cite a study that finds “median household income in London is 14% higher than the UK average before housing costs, but only 1% higher than the UK average after housing costs… high house prices erode any net economic gains for most people from in-migration to London from other regions.”

Skills policy should be seen as a two-step process. Step 1: Teach people useful skills. Step 2: Match those people to jobs where they can use those skills productively. Yet, the debate around skills typically only focuses on Step 1.

Physical infrastructure matters a lot for Step 2. When housing supply is constrained and the benefits of productivity gains are eroded by rising rents, workers do not move to the jobs where their skills are best used. And where a worker works has a big impact on how productive they are. Overman and Xu find that, after controlling for things like education, a worker moving from the UK’s least productive region to its most productive region experiences a 17% wage boost.

I’m reminded of a paragraph from Duncan Weldon’s Economist article on Barratt Britain.

In Cramlington, Richard, who works in sales, earns around £28,000 a year and his partner, a part-time administrative assistant, earns £12,000. That is enough for a four-bed house and two cars. “If I’d moved to London and got a graduate job, I’d probably be renting a shitty flat and I doubt I’d have two kids,” he says.

Part of the reason that workers are more productive when they are in London is because of agglomeration effects. There are a few big advantages to having a large pool of labour. To start with, it draws in employers. And as Adam Smith taught us, the larger the market, the deeper the specialisation. Workers can take a risk and specialise in really niche roles in the knowledge that they’ll have multiple options in a big city. By contrast, in a small town there’s a risk that if they lose the job they are best suited for, they won’t be able to replace it with anything close to as suitable.

To boost growth outside of London, the focus should be on creating similar agglomeration benefits by building more homes and improving transport connectivity in large cities outside London.

In France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US, there’s a strong correlation between how big a city is (in terms of population) and how productive that city is. But if you exclude London, that relationship doesn’t exist for the UK.

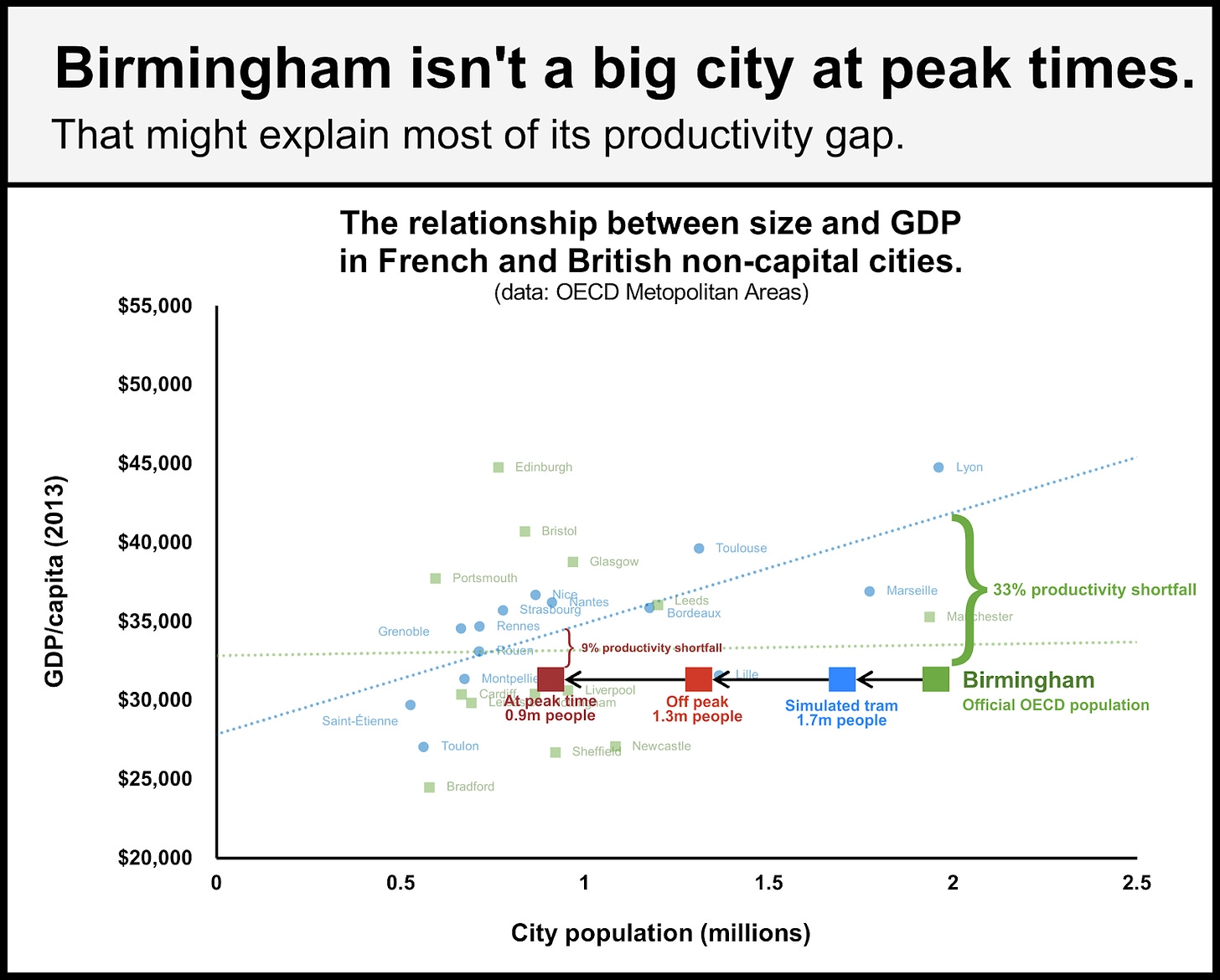

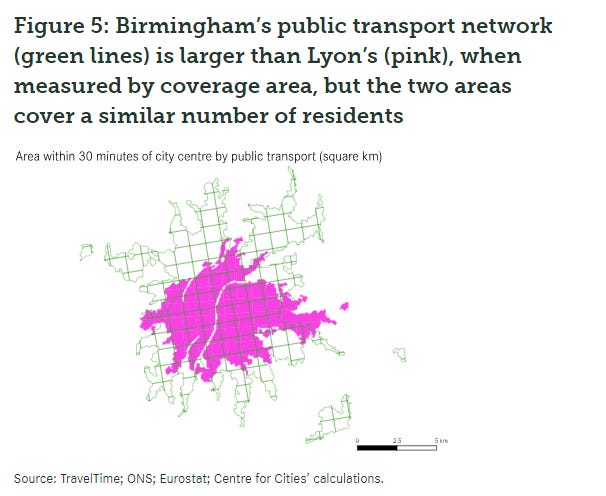

Why don’t Britain’s cities benefit from similar agglomeration bonuses? Tom Forth argues it is because they are only big on paper. The OECD lists Birmingham’s population as being 1.9m people, yet at peak travel time (8am to 9am) only 0.9m people can reach the city centre within 30 minutes. And it turns out Birmingham is about as productive as you’d expect for a city of 0.9m.

The problem is that the roads are too congested, public transport is unreliable and slow, and where there are fast transport links too few homes are built. This is a problem across the UK.

Consider the following stats from Stansbury, Turner, and Balls:

Roads in British cities are 48% more congested than roads in similar US cities, and 15% more congested than roads in similar European cities,

At rush hour, the area accessible by car within 30 minutes is much smaller in British cities than US cities and the area accessible by public transport is much smaller than for almost all European cities.

Public transport in British cities outside London and the South East is extremely unreliable. More than one in every twenty-five trains was over fifteen minutes late for seven separate operators. Punctuality rates are low by EU standards, while cancellation rates are high.

And despite the trains often arriving late (or being cancelled), some railways across the UK have London-style rush-hour crowding. In fact, during peak time on the most popular commuter routes into Birmingham one in four passengers is forced to stand.

Yet investments in more and better roads, railways, and trams will only get us so far. I’m struck by this graph from Centre for Cities researchers Ant Breach and Guilherme Rodrigues.

Put simply, to get the benefits of agglomeration we not only need to build better transport links, we need to allow new houses to be built at high densities near them too.

***

Is there room for improvement in education and training policy? Of course, there is.

For a start, we should turn the Apprenticeship levy into a new flexible Training levy, allow workers to claim tax relief on self-funded training (most OECD countries do this), and have much greater employer involvement in course design so students aren’t taught skills that are out-of-date before they have even entered the workforce.

Yet, the main constraint on growth in the UK is not caused by a lack of training or spending on education. It is caused by a failure to build the necessary homes, energy infrastructure and transport connections to allow those skills to be employed productively.

And this is what prices tell us. The premium employers are willing to pay for workers with a university education or specialist skills training may have fallen, but the premium developers will pay for a plot of land with planning permission is extremely large. In fact, the value of an acre of Green Belt land can increase one hundred fold when planning permission to build new homes is granted. The cost of building a new home or a new lab is far less than what a new home or lab sells for on the market. In fact, in London a new home can go for four times what it costs to build one.

Fixing this should take priority.

Image credit: David Robinson

A point on transport links. I live in the South West which has fast and reliable trains to London but a season ticket from Swindon to Paddington (55 mins) is over £11k a year, making it unaffordable to all but high earners.

Agree with much of this, but not the premise that lurks behind your housing supply solution. On standard theory the fact that there's no difference in AHC incomes in London versus elsewhere is a feature of land, not a bug that can be fixed. Land (largely) captures the urban surplus and it's therefore inevitable that the cost of building a house is much less than the cost of the property. As you build and boost agglomeration in a city, productivity rises and land values follow. So yes, by all means build in cities to boost agglomeration, but you can't change AHC incomes that way.