Is China doing anything about Climate Change?

To China, the cause of, and the solution to, all of the climate’s Problems

China emits more greenhouse gases than any other country, by a long way. It is building more renewable and nuclear power capacity than the rest of the world combined. It is also building more coal power plants than the rest of the world combined. China’s policies are enabling a faster global transition away from fossil fuels than many once thought possible. Yet domestically, it is doing nowhere near its fair share to combat climate change. The Chinese government genuinely cares about climate change. When setting energy and environmental policy, climate rarely ranks higher than fourth on its list of priorities.

All these statements are true. And by selecting only some of them, China’s defenders, China hawks, net zero skeptics, and green evangelists can each build a completely factual, but deeply misleading, narrative.

A clearer story emerges when these truths are held together. China does care about the climate, but it cares more about energy security, keeping costs down and building world-beating industries. When climate goals align with these higher priorities, China moves faster and on a larger scale than any other country, shifting global trends in the process. When they conflict, progress slows to a crawl.

China is the world’s biggest emitter

There are lots of ways to measure emissions. China is either far out in front as the biggest emitter or very high in the rankings on all of them.

The most common way to measure greenhouse-gas emissions is territorial CO₂ equivalent. China emits more CO₂ equivalent than the US, the EU, India, Japan and the UK combined.

The second most common way is consumption emissions. Under territorial emissions something produced in China, but consumed in the UK would be counted as China’s emissions. Under consumption emissions it would count as the UK’s emissions. China as a major exporter looks a lot better under this metric. However it is still the world’s largest emitter. And it is still not particularly close.

Of course China is the world’s 2nd most populous country. While the figures above prove that the Chinese nation is having the biggest impact, maybe this is all just down to the number of people they have and we should use per capita emissions. Even using China’s favoured consumption metric that’s not really the case:

In 2022 China was emitting, on a consumption basis, as much carbon as developed countries like the UK and only marginally less than the EU. China’s emissions have increased marginally since 2022, while the UK’s and the EU’s have fallen, so China likely now has a bit of a lead. Clearly some developed countries (the US, Australia, wealthy oil states) are emitting significantly more than China per capita. But, as the graph shows, China is way ahead of the emissions of the developing countries they seek to ally themselves with in international climate talks.

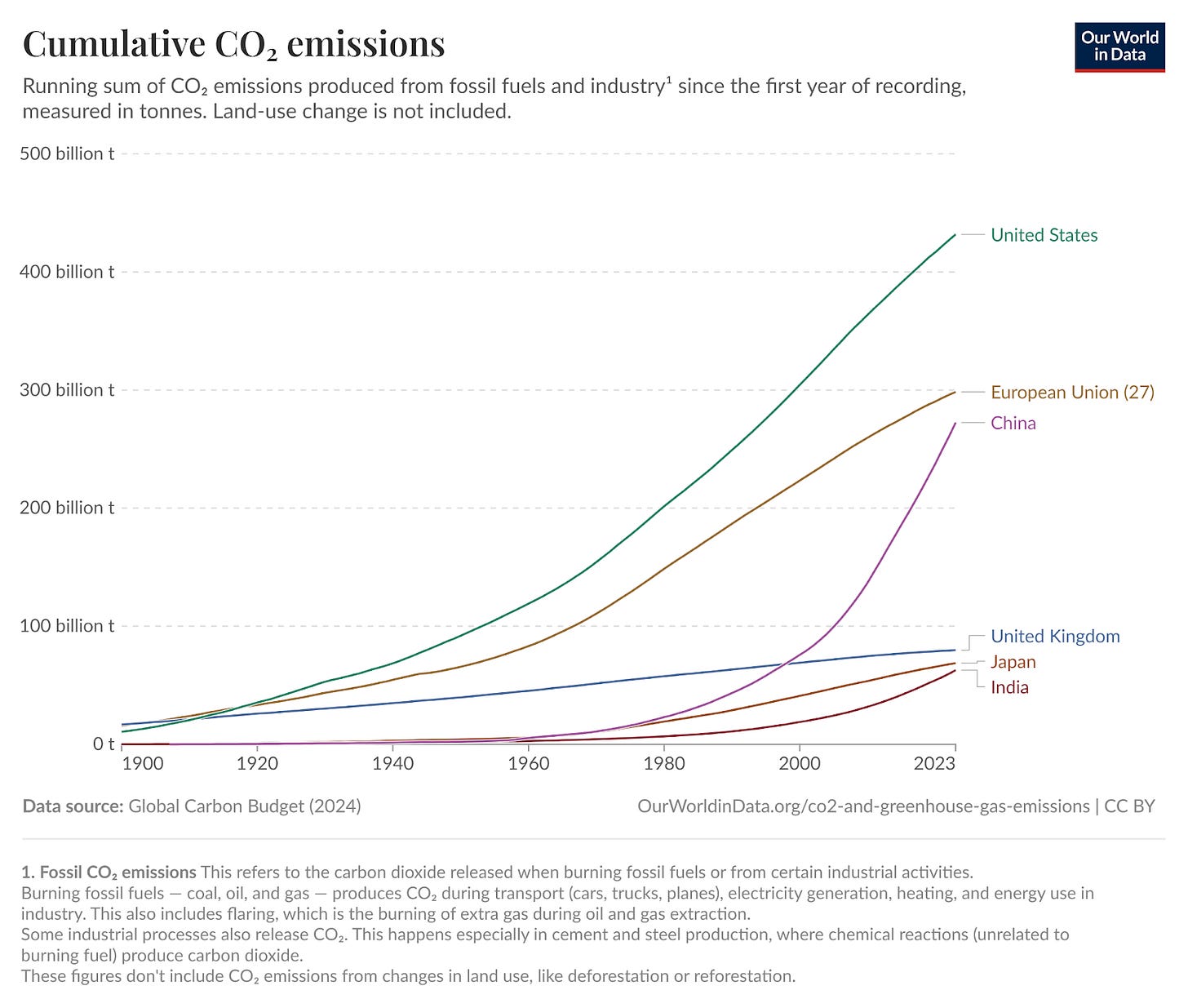

Historical emissions are another metric that is used. The reasoning here is that climate responsibility lies with countries that have emitted more over the whole of history, rather than who happens to be emitting the most now. As China’s economic growth is very recent, only beginning in the late 1970s, they do look a bit better by this metric:

China has emitted 15% of CO₂ equivalent emitted in history. While that is only the third highest number, they will likely overtake the EU into 2nd before the end of the decade. It’s possible that they may never overtake the US.

Historical emissions are also arguably a bit unfair on early developers like the UK. The problems of climate change were not known in 1900 to many. Also there were no alternatives to burning fossil fuels available if you were industrialising. Modern Chinese policymakers have a lot more choices in this area than politicians did in Victorian Britain and Ireland.

Taken together, these metrics show that China’s high emissions can’t simply be explained by population or export patterns. Whether measured by territory, consumption, or history, China’s contribution to climate change is vast, and still growing.

China is building out green technology faster than anyone else

Solar

China has been the world’s largest installer of solar every year since 2012, usually by a very large margin. As the graph below shows they have installed substantially more than the rest of the world combined in recent years. 1GW is roughly one large coal or nuclear power plant of capacity.

Wind

The story with wind is very similar.

China is installing more wind than the rest of the world combined.

Nuclear and Hydro

Compared with its renewables build-out, China’s nuclear build-out is slow. They ‘only’ have around 55GW of capacity, which is less than France (63GW) and far behind the US (97GW). However, with 33 nuclear power plants under construction China is building almost as much nuclear power as the rest of the world combined. Crucially they are also keeping the costs down. China uses a ‘fleet approach’ for new nuclear, building multiple versions of the same reactor so lessons can be learnt and a supply chain can be built up.

Hydroelectric power is currently the main source of renewable energy in China, providing 13.5% of China’s electricity in 2024 (compared to 9.8% wind, 8.3% solar, 4.4% nuclear and 58.2% coal). However, there is limited room for expansion. All but two major rivers in China are already dammed and much of the remaining capacity will be used for pumped storage hydro, where dams essentially serve as a giant battery with water being pumped into the dam when wind and solar are plentiful, and the water being let out to produce electricity when they are scarce. There are still megaprojects underway, China is constructing the world’s largest hydroelectric power station in Tibet, and the world’s tallest dam in Sichuan. But such is the scale of China’s renewables rollout that it doesn’t make much of a dent compared to the nuclear, wind and solar plans.

But what about coal?

China is also building more coal than the rest of the world combined. In 2023 China built 95% of the coal power plant capacity in the world. In 2024, coal power plant construction surged to a 10 year high.

Chinese climate negotiators often point out that the capacity factor (how often plants run) of China’s coal fleet is only 50% and falling, and that as a percentage of their electricity mix coal is falling. That is all true:

But there is no getting away from the fact China is using more and more coal power every year.

It is also important to bear in mind that for all forms of generation the vast size of China’s population and economy. When you look at per capita generation China is still a very heavy user of coal, and its renewables and nuclear generation are still fairly impressive.

The best figure for considering the impact of a country’s emissions impact from its electricity output is the carbon intensity of its grid, which is the amount of emissions per unit of electricity produced.

Here China is clearly worse than most developed countries and the world average. It is also emitting slightly more per unit of electricity than the average for upper middle income countries (places like Brazil, Turkey and Malaysia).

Nevertheless it is true that China is building more renewables and nuclear than the rest of the world combined. The short version of China’s energy generation policy is that China is building huge amounts of most types of energy generation, no matter how clean or polluting it is. So what explains this ‘all of the above’ energy strategy from the Chinese government?

China is a fast growing middle income country with a massive population with rapidly growing energy demand

The most important and the simplest reason for China’s all of the above approach is that they need a lot of energy. China’s energy use has doubled since 2012. Per capita energy use in China surpassed the UK (where energy use is decreasing) in 2021 and is still just short of EU levels. Given China’s huge industrial sector, domestic energy consumption is still likely significantly below UK and EU levels. It is certainly far below most other developed countries’ levels and therefore has huge potential to keep on growing.

China has a huge population. It is a middle income country. As the correlation between GDP and energy use is very strong, China’s energy output was always going to increase as their economy grew.

A lot of the reason for an ‘all of the above’ strategy is simply that China needs to build all the energy it can get to meet demand.

Energy security is the top priority

The official top priority of China’s National Energy Administration is achieving ‘energy security at a high level’. Former Chinese President Hu Jintao was talking about the ‘Malacca Dilemma’ for Chinese energy policy as far back as 2003. China imports over 3 million barrels of oil a day. Most of it from the Middle East via the Malacca Strait, a body of water between 40 and 65 miles wide between Indonesia and Malaysia, that could likely be easily closed by the American Navy in a conflict scenario.

China is actually the world’s 5th largest oil producer, producing 4.4 million barrels of oil a day in June 2025. However, their consumption was over 8 million barrels a day in 2024. One way they deal this is with a vast oil stockpile of over 1 billion barrels of oil. The other is reducing oil demand by electrifying the whole economy.

The biggest component of that is electric cars.

As the above graphs show this is yet another area where China dominates the adoption of clean technology.

China’s efforts to electrify their economy are working. 29% of their energy comes from electricity in 2023. The current figure is likely substantially higher.

This has started to achieve their goal as oil use is plateauing and arguably beginning to decline.

As well as helping their energy security, electrification of the entire economy is likely necessary, though not sufficient, for net zero. China is making significant progress. Climate action is not China’s main reason for swapping out oil use for electricity, but as a side effect of their push for energy security they are making climate progress.

When energy security and climate action conflict, China chooses energy security. One of the main ways the UK and many other developed countries have reduced their emissions is by switching from coal to gas. Coal emits around twice as much CO₂ per unit of electricity produced compared to gas. 67% of the UK’s electricity came from coal in 1987, with just 1% from gas. By 2022 coal was down to 2% and gas was up to 38%. There is now no coal on the UK electricity grid. The UK’s switch has been dramatic but it has happened at a slower pace in many other countries, with the US going from 57% of their electricity from coal to 15% coal from 1988 to 2024 while gas rose from 9% to 43% in the same period.

China has not and will not do this. As Xi Jinping once put it, China is ‘rich in coal, poor in oil and low in gas.’ China produces around 90% of the coal it consumes. Despite getting just 3% of its electricity from gas, China imports 39% of its gas. Any attempt to transition from coal to gas to reduce China’s emissions would rely on massive imports. China is not willing to put its energy security at risk in that way, nor would such massive extra demand be welcome by other gas importers (like the UK) around the globe as we would end up paying higher prices.

Energy security doesn’t just mean not relying on foreign suppliers. It means being able to reliably provide electricity to everyone (and every factory) in the country. If I was writing this piece in the late 2010s I may have been tempted to write that China’s coal use was soon going to peak, and that their building of coal power plants was slowing down. However as noted above there has been a massive surge in coal power use and coal power capacity buildout since then. This is because, in the early 2020s, China experienced massive power cuts. There were prolonged outages for industry in twenty of China’s thirty eight provinces. In the Northeast there were also power outages for residential users. This was a deeply embarrassing failure for China’s energy policymakers.

Most analysts agree that a lack of supply wasn’t the issue. A mix of poor market design and fixed prices meant that coal power plants shut down during the power cuts as they would have lost money. Another issue in the early 2020s was that poorly designed environmental targets meant many areas operated as normal until their centrally set energy budget was nearly exhausted, then simply ordered factories to close. The central government has taken substantial steps to fix these issues and I will examine how building a functioning power market is cutting China’s emissions later in this piece. But Chinese policymakers are clearly scarred by these power cuts and National Energy Administration documents regularly refer to these outages and make it clear they will not be allowed to happen again. Part of their response was taking power market reform more seriously. But they also ensured that, while commitments to ‘phase down’ coal remained on paper, more coal capacity was built to ensure these blackouts never happen again.

Xi Jinping examining a coal depot in 2021, providing reassurance that power cuts wouldn’t happen again.

Energy security comes before climate action every time in China. Sometimes energy security aligns with climate goals, by encouraging them to build functioning power markets and increase the use of electric cars. But it also means not using gas and building a lot more coal.

The cost of energy is a top priority

China has very cheap electricity.

Direct comparisons are slightly complex and I have excluded standing charges to make it easier. However, this comparison is actually unfair on China. In Korea standing charges add about $10-30 a year to bills, in the US it adds between $60 and $240 a year, while the UK average standing charge is $286. In China it is zero.

Industrial prices in China are a little higher than domestic ones, while in most developed countries it is the other way round. Nevertheless, China still has substantially cheaper electricity than developed countries no matter how you slice it.

There are things that China does to keep electricity cheap that are probably not advisable in the long run. Some of the financing mechanisms, especially for underutilised coal plants, look dubious and ultimately are subsidies from future Chinese taxpayers for cheap energy today. However, the main mechanism is simply keeping construction costs low. Whether it is coal, nuclear or renewables China has a massive domestic supply chain, unencumbered by endless red tape, fish discos and judicial reviews, that can deploy rapidly and at scale and therefore at low cost.

China’s industrial strategy backs the energy buildout

As discussed in piece four in this series, China has a fairly typical East Asian industrial strategy. Wind, solar and electric cars have all been some of the beneficiaries of this ‘picking sectors’ (as opposed to ‘picking winners’) approach they have pursued. Creating a large domestic market for these products is necessary to build these industries. While most of China’s energy policies are driven by economic and security concerns, there are also areas where genuine climate ambition is visible.

The Communist Party does actually care about climate change

China’s climate targets are a mix of the unambitious, the difficult to measure or targets they have totally failed to meet.

China has an unambitious target of peaking Carbon Dioxide emissions before 2030 and cutting emissions by 7% by 2035. However when both of these targets were announced, they were actually below what most analysts thought China would achieve if they didn’t change their policy at all.

China’s 2060 net zero carbon target is difficult to measure. It is always possible to claim you are on track for long term targets by promising to cut emissions faster but later.

The one ambitious target China does have, their carbon intensity targets, they have totally failed to meet. Carbon intensity is your carbon emissions divided by your GDP. China’s target was to reduce their 2020 carbon intensity by 18% by 2025. Independent analysis showed China needed a 4-6% cut in emissions to achieve this target. Early indications are that emissions have stayed flat.

Even though they are failing on this specific target, China is taking some climate actions that cannot be wholly explained by the more pressing reasons explained above that determine most of their energy policy.

One clear example of China taking real climate action is its long-running support for renewable energy. In 2009 for wind and 2011 for solar, China introduced very generous feed-in tariffs, offering renewables roughly three times the rate paid to coal power plants. These subsidies triggered an extraordinary build-out of wind and solar capacity throughout the 2010s.

As costs fell and domestic supply chains matured, the government began to scale back national subsidies. By the end of 2020, most new projects were guaranteed the same price as coal plants. This still represented an effective subsidy, since renewables provide intermittent power while coal offers dispatchable, round-the-clock generation. Even parity pricing therefore continued to favour renewables in practice.

From 2026, China will shift to a new system similar to the UK’s Contracts for Difference. Each province will set a quota of renewable power to procure, and developers will compete in auctions, bidding the price at which they can deliver electricity. Projects that fail to secure contracts will either not proceed or sell power on wholesale markets. The recent surge in renewables construction before the old regime ends suggests that many developers expect the new arrangements to be less generous.

The overall cost of these subsidies is difficult to quantify, but they have clearly played a decisive role in lowering China’s renewable costs, accelerating deployment, and cutting emissions. This decade-long commitment shows that Beijing is willing to spend heavily on climate action, provided it also strengthens energy security and industrial competitiveness.

Another example is China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS). It has often been criticised as weak or symbolic. To date, those criticisms have been fair. The current system covers only the power sector, steel, aluminium, and cement, leaving around 40% of emissions outside its scope. It also lacks a binding national cap, functioning more as an emissions efficiency mechanism than a hard limit. Power plants, for instance, are allocated emissions allowances based on how much electricity they generate. The most efficient coal plants effectively receive all the permits they need, while older, dirtier ones must buy additional credits, a modest incentive for upgrading, but hardly transformational.

Yet the direction of travel is clear: China does intend for the ETS to become a serious climate policy tool. Officials and policy documents increasingly describe it not merely as a data-gathering or pilot exercise, but as a core mechanism for achieving national climate goals. The government recognises that transparent carbon pricing is essential to balancing its long-term objectives, including promoting low-carbon technologies, improving industrial efficiency and retaining competitiveness in global markets that are themselves moving toward carbon border adjustment taxes.

However, China will move cautiously. The leadership’s priority remains stable growth, energy security, and social stability. Any policy that risks undermining these will be phased in slowly and pragmatically. For this reason, the ETS is being expanded sector by sector, allowing data systems, compliance monitoring, and market institutions to mature before harder caps are introduced. By 2027, it is expected to cover all major industrial emitters, and by 2030 it should include absolute emissions limits in key sectors. But the caps are likely to tighten only as confidence grows that cleaner energy supplies, industrial upgrades, and grid reforms can sustain economic performance.

In short, China’s ETS is a work in progress. It reflects the same logic that drives much of China’s climate policy: genuine intent to reduce emissions, pursued at a pace and scale that never endanger its higher priorities of energy security, affordability, and industrial strength.

China is also implementing market reform policies that should improve energy security, reduce costs and reduce emissions simultaneously. At the moment China has lots of coal on long term contracts that mean it gets used even when renewables are available. The claimed ultimate aim of China’s power market reforms is to create a system with Contracts for Difference funded renewables, supported by a wholesale market for fossil fuel generators that can back them up. This will sound familiar to anyone who knows the UK energy market.

What is China actually doing?

China is taking serious and sustained action on climate change. This is mostly not out of altruism but because doing so supports its broader goals of energy security, industrial strength and cost control. Its clean-tech buildout has transformed global supply chains and made the world’s transition away from fossil fuels faster and cheaper than it otherwise would have been. Yet climate action remains only one of several competing priorities in Beijing’s energy strategy.

China’s position is unique. As the source of over a third of global emissions, what happens inside its borders genuinely shapes the planet’s climate trajectory. The UK’s situation could not be more different: we account for less than 1% of global emissions. Our direct impact on the atmosphere is small, but the example we set matters. At present, though, the UK serves as a warning rather than a model. Our high energy prices, the highest in the developed world, make our path unattractive to others.

China treats cheap, secure energy as the foundation of its green transition. China may be copying our market design, but if renewables auctions return very high prices it is almost certain that deployment will be delayed until prices fall. Failing to place energy prices at the centre of our considerations is going to make the green transition impossible in the long run. First, because high prices slow the adoption of electric cars and heat pumps. Second, because high energy prices are destroying the political consensus that we should have a green transition at all. If the UK wants to lead by example, we need to get prices down. China already has some elements of locational pricing and is going to have CfDs awarded province by province. This will mean renewables will be located where they can best access demand, driving down costs. Ed Miliband rejected this approach for the UK after intensive lobbying from energy companies, even though it would have lowered bills. Now the big decision is both how fully and how quickly to adopt the recommendations of the Prime Minister’s Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce. Adopting the recommendations in full would dramatically reduce the cost and the speed of future nuclear building, for both traditional Giggawatt scale plants and for Small Modular Reactors. If we are serious about getting bills down, getting emissions down or increasing our energy security it is the obvious thing to do. If they are in any doubt, maybe Minister should ask, what would China do?.

‘Failing to place energy prices at the centre of our considerations is going to make the green transition impossible in the long run.’

You would indeed hope that it was blindingly obvious that high power prices are probably the biggest impediment to widespread electrification and thus decarbonisation of our economy and yet judging by AR7 not to our politicians and policymakers.

Excellent article.