Is offshore wind really 40% cheaper than gas?

We need a better energy debate

“The price of wind we’ve secured is 40% LOWER than the cost of building and operating a new gas power plant.”

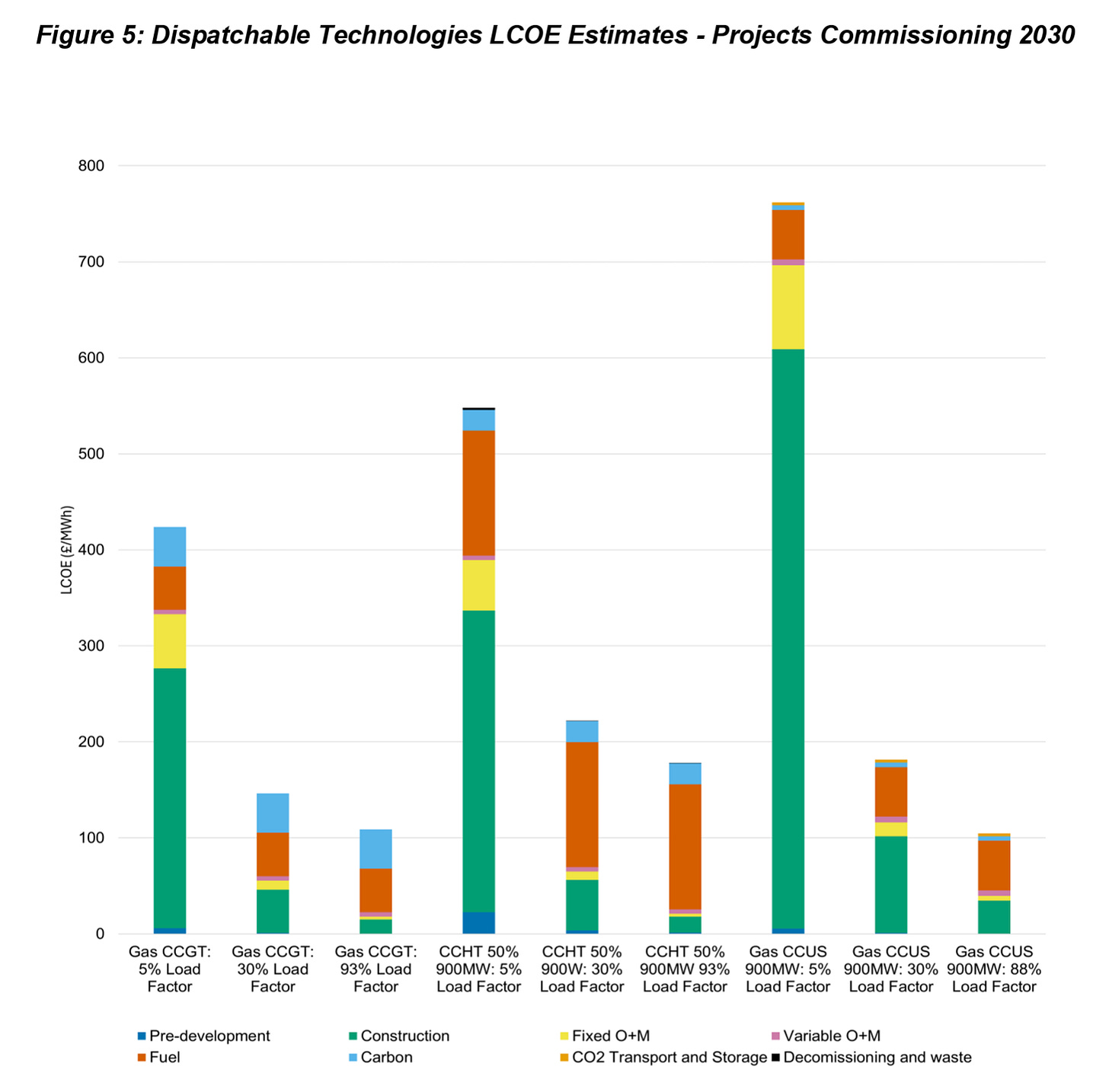

This is Energy Minister Michael Shanks MP’s defence of the Government’s decision to lock in 20-year contracts for 8.4GW of wind power at £91 per MWh. DESNZ’s data (published yesterday) estimates that the levelised cost of energy for a new gas plant built in 2030 is £147 per MWh.

In essence, he’s arguing that even if £91 per MWh is more expensive than energy is at the moment, it isn’t more expensive than building more gas plants in the years to come. Comparing new wind with old gas plants fast approaching decommissioning.

Shanks is right to look forward (and not at current prices). Britain’s existing gas fleet is old and in need of investment. Nearly a quarter of the existing capacity was built in the 90s. Gas appears cheaper than it is because we are sweating a fleet that won’t be there in a decade. And it has become more expensive to build new gas plants due to the surge in demand from AI hyperscalers like Microsoft.

Shanks’ argument has elements of truth, but I think it is ultimately misleading.

First, the high cost of new gas is partially a policy choice. Gas power emits CO2, which causes climate change. Britain imposes a carbon tax on gas so the polluter pays for the damage they cause. This represents around 30% of the cost of building and operating a new mid-merit gas plant on DESNZ’s assumptions. If this carbon price was scrapped, as Reform and the Conservatives now advocate, then the LCOE for new gas would fall to a £105 per MWh.

I am in favour of carbon pricing, but when advocates talk about ‘gas being expensive’ without making clear that we deliberately make it more expensive in order to tackle climate change, they are, deliberately or not, muddying the waters to create the impression that decarbonisation is without trade-off.

Second, high carbon prices and more wind on the grid also push down gas load factors. In the past, gas plants ran most of the time. In the future, they may go weeks without switching on. With lower carbon prices (and less wind on the grid), we would also sweat our gas assets to a much greater extent. The £147 figure is based on a gas plant running at 30% capacity.

Run it at 93% and costs fall to £109 (and £69 excluding carbon prices). At low capacity factors, there’s less generation to spread fixed costs like construction across.

Sidenote: It is more than a little frustrating that they modelled 93%, which no one expects to be reached, rather than 70% which was average capacity hit between 2014 and 2024.

Third, LCOE is a flawed metric. While it can be helpful to track cost increases or decline for a given technology, it can mislead when you compare technologies. Nuclear runs 24/7 at a high capacity factor, wind is intermittent, and gas can fill the gaps. If you only look at the LCOE, you ignore the big benefits of baseload (nuclear) and dispatchable (gas and coal) forms of generation.

Fourth, even if we build loads of wind generation, Britain will still need new gas plants to fill the gaps when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining. And the Government is planning to order new gas plants. The debate then isn’t just whether or not to build new gas plants, but whether to run them at higher or lower capacity factors.

We deserve a better debate. Our current debate isn’t sustainable. What we have today is a legacy of a brief period after the gas crisis where wind and solar were indisputably cheap. Back then there was no energy trilemma. Energy security, decarbonisation, and affordability all pointed us in the same direction: a dash for clean power. Since then gas prices have come down and the cost of building wind farms has gone up.

We need to be able to engage with trade-offs. First, because the public cares about this and if bills don’t come down, then there will be a backlash. Second, the trade-offs matter for decarbonisation. There is no way to reach Net Zero without mass electrification. And electrification will only succeed if it is a good deal for consumers. There is no point in decarbonising the grid, if it stops us from decarbonising our heating, transport and industry.

You are asking the right sorts of questions here.

One thing you perhaps need to get your head around is the carbon price that DESNZ adds to gas-fired power. There is an economic case for adding the cost of the externality (harms of global warming), but that isn't what DESNZ do. Instead they add an figure which they call "the target-consistent carbon price". It is nothing to do with the externality, or even with carbon, but is simply an arbitrary value designed to make Net Zero happen regardless of the economics.

Your point about LCOE being an inappropriate metric. It is also noteworthy that DESNZ's 30% capacity factor for gas is being compared to unconstrained wind output. That of course is not what is happening now - we are paying windfarms all the time to switch off. The levelised cost of Seagreen, for example is in the range £86-111 if you pretend it is never curtailed. It's £269-390 if you don't. This is expected to get much worse because we are increasingly adding system imbalance curtailment to the thermal constraints costs.

My advice is to ignore all numbers coming out of DESNZ.

Sam,

the government aim for just 5% of generation being gas.

This is not a realistic target and we actually need to get new gas generation on line as soon as possible, the current fleet is ageing and nuclear is on a downward capacity trend as they also are near end of life.

Unfortunately global demand for gas generators is increasing and lead times are several years forward.

We need to run gas 100% of the time as that is what keeps the grid in load and demand balance

and even at low output it provides essential technical attributes that wind and solar lack. It is a very poor way to run what can be extremely efficient generators, thus adding a cost to the consumer and increasing maintenance costs as well.

Essentially we are running duplicate generation where gas alone could do the job without the expense of building wind turbines and the extensive and unsightly infrastructure it requires.

The mistake was made over twenty years ago to ditch a planned nuclear expansion and instead go for unsuitable wind. Instead of learning of all the deficiencies years ago we continue with them at our very high cost. Rarely mentioned is that wind and solar output declines steadily with age and the life span is short relative to conventional generators. Impractical, costly, unreliable and at times very unstable with, to my mind no redeeming features in using renewable generation.