Renew London's estates

How an estate renewal revolution can build half a million homes and cut London’s emissions

In the run up to London’s Mayoral Election on May 2nd, we’re sharing sections from Get London Building, Britain Remade’s plan to tackle London’s housing shortage. In the first post in this series, we tackled the issue of density, calling for a New Zealand style upzoning of London’s brownfield land near train stations to cut emissions and rents. In the second, we made the case for building on some of London’s 95 (!) golf courses. In the last post, we looked at industrial land and the opportunity to build near the new Old Oak Common station. In the final post in this series, we explain how estate renewal could unlock half a million homes while cutting London’s emission — all without costing the taxpayer a penny in the long-run.

Too many Londoners live in homes that are cold, damp, and crowded. Improving the quality, not just the quantity, of London’s housing stock is vital to cut bills, to cut emissions, and to cut preventable cases of ill health.

In the 1960s and 1970s, London’s boroughs built tens of thousands of new council houses, but they were not built to last. Many post-war council estates are now in an unacceptably poor condition. More than half of all social homes do not meet the bare minimum energy efficiency standards that all new homes will soon be forced to meet. Almost a quarter of council properties lack double glazing; one in 10 homes are forced to heat their home with expensive inefficient electric space heaters; and more than half (54%) lack insulation altogether.

Upgrading London’s homes to be warmer and safer won’t be cheap. Take Cheshire House, a 1960s tower block in Enfield, residents were left without heating and forced to take showers outdoors in the freezing cold due to a gas leak. To bring the building up to standard would cost £54m – simply unaffordable – so the building will be demolished instead with residents forced to leave their homes.

There’s a better solution: estate renewal. Ham Close in Richmond is another poorly built 1960s council estate where residents live in cramped and unsafe conditions. Many are forced to buy expensive-to-run dehumidifiers to fight back damp. But, things are finally looking up for residents of Ham Close. A scheme backed strongly by residents to knock-down and rebuild the 192-home estate with 452 new homes has won planning approval. Every existing resident will get a new home that’s warmer, bigger, and most importantly, safer. Unlike often expensive retrofits, estate renewal can be done without any long-term cost to local authorities.

This is possible for two reasons. First, the capital’s post-war estates were built at densities far lower than many of London’s best-loved historic neighbourhoods. Marylebone, for example, is built at more than five times the density of many post-war estates. Some of London’s best designed new neighbourhoods, such as Millharbour on the Isle of Dogs, reach even higher densities.

Second, London’s planning system is so restrictive and house prices are so high that new London homes sell for four times the cost of actually building them. This creates a massive surplus that can be used to fund the building of better quality homes for existing council tenants and a net increase in the social housing stock. It’s a win-win.

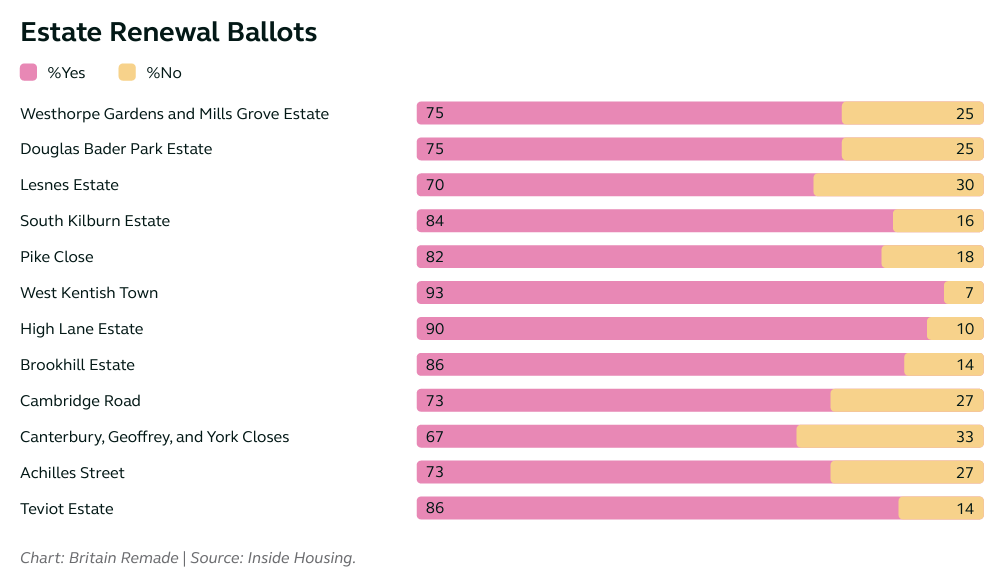

Since 2018, estate renewal can only happen when a majority of residents back it in a ballot. When given a choice, most people vote enthusiastically for a bigger and warmer home. In fact, 29 of 30 estates balloted on renewal supported it the first time they were asked. In some cases, over 90% of residents voted to redevelop their estate.

There are around 540,000 council homes in London, which together take up roughly 7,344 hectares of land. At a density of 73 dwellings per hectare (ha), London’s council estates are roughly three times less dense than Maida Vale, which is the densest square kilometre in the capital. Maida Vale achieves high levels of density, not through imposing concrete towers, but through gentle density – attractive Edwardian mansion blocks complemented by communal gardens.

London’s post-war estates were often isolated from the wider streetscape – the so-called ‘tower in a park' model. This also means that euphemistically named ‘green space’ is typically on the outside of blocks, and hence barely used, rather than on the inside as usable shared or private gardens. Redevelopment is an opportunity to repair London’s urban fabric and re-integrate communities. It is possible to rebuild estates at much higher densities using only mid-rise housing such as mansion blocks in popular architectural styles. In fact, real estate company Savills estimate that rebuilding London’s estates in this style would deliver an average of 135 homes per hectare.

The opportunity is massive. Rebuilding London’s estates at modest densities could deliver over 530,000 extra new homes on top of the 540,000 rebuilt and upgraded social homes. Aiming for even higher densities in some of London’s best connected boroughs (Camden, Islington, Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Southwark, and Lambeth) could add 185,000 new homes alone and fund a bold expansion of the council housing stock to house local people stuck on the waiting list.

As build costs are just a fraction of house prices, at sufficient densities projects would generate a massive surplus for the council to spend on their priorities whether it is more affordable housing, more council housing, or helping local people insulate their homes. Newham council’s renewal of The Carpenters estate will add 762 brand new homes at social rent for local people on top of the 314 existing social homes that are being upgraded to highest possible energy efficiency standards.

Not only will regenerating London’s estates tackle the capital’s extreme housing shortage and cut council housing waiting lists, it will also save money and mean fewer cases of ill health for current residents. If all new estates are built to the highest energy efficiency standards, the average council tenant would save almost £800 a year in lower gas and electric bills – a two-thirds saving.

By cutting energy use in the capital, estate renewal can play an important role in reducing London’s CO2 emissions. As it stands, the average council house emits 2.62 tonnes of CO2 each year. If every council house was replaced by a new home built to the highest energy efficiency standards, it would cut London’s carbon footprint by nearly 1m tonnes – equivalent to taking almost half a million cars off the road.

What are the barriers to estate renewal?

To supercharge estate renewal in London, the Mayor must tackle some key problems.

The pay-off from estate renewals is often massive, both in terms of new homes built and lives transformed, but these are long term projects. In the best projects no resident is forced to move twice, but this means more slowly in the early stages. For example, the 4,800-home renewal of Kidbrooke Village in Greenwich will take 20 years. Even before a project has been approved, housing associations and councils must engage with residents, develop designs, and go through planning. All of this is expensive.

To combat this the Mayor of London should create a new fund to support boroughs and housing associations to develop high-quality projects that meet the highest energy efficiency standards in partnership with residents, run ballots, and go through planning. Due to the massive potential to cut London’s emissions, the Mayor should look at finding ways to leverage the Mayor of London Energy Efficiency Fund to provide cheaper funding.

The Mayor of London’s office should proactively identify estates with high renewal potential and use their convening powers to get registered providers (i.e. housing associations or local authorities) to work with residents to draw up a plan.

To further support housing associations and local authorities to deliver estate renewal projects, the Mayor of London should negotiate the flexibility to borrow at the same rates as central government for renewal projects. Additionally, the Mayor should lobby for local authorities to be given more flexibility to spend any revenue generated through estate renewal on their own local priorities, whatever they are.

It is rare that estate renewal projects are rejected by councils, but it happens. The Aberfeldy Estate in Poplar is walking distance from Canary Wharf. The estate was built as mostly low-rise terraces before the docklands regeneration made the location much more desirable. A proposed scheme to redevelop 330 council-built homes on the site into 1,582 homes (including 447 homes at social or affordable rates) was rejected 8-0 by Tower Hamlets’ Strategic Planning Committee on spurious grounds. It was blocked by Tower Hamlets councillors even though it had overwhelming support from residents with 93% voting in favour.

Mayor Sadiq Khan has rightly used his ‘call in’ powers to take this decision out of the hands of Tower Hamlets. Approving a project that both adds over 116 homes at social or affordable rents and helps tackle London’s market-rate housing shortage near a major employment centre should be an easy decision for the Mayor.

Yet while planning refusals for estate renewal schemes are rare, the planning system can still have a chilling effect. The viability of any scheme depends on how many homes can be sold at market rates. Creating new amenities for residents, increasing the share of new council housing, and delivering bold energy efficiency initiatives such as heat networks or communal heat pumps all depend on how dense a site can be. The most ambitious schemes can only succeed if they’re allowed to be built at higher densities where there is a higher risk of objections and planning being rejected.

To provide certainty to housing associations and local authorities, the Mayor of London should set clear policies on recommended densities for estate renewal projects. In the best-connected and most expensive parts of London, high densities, including well-designed towers, should be explicitly allowed in order to ensure projects that meet the needs of existing residents can be viable. Where projects go above and beyond in delivering new affordable and council housing for local people, or in meeting green objectives, higher densities should be allowed. In lower density and less well-connected areas, mid-rise projects that reach the densities of London’s best-loved neighbourhoods such as Marylebone or Maida Vale should be explicitly allowed. The Mayor of London should commit to call in and permit any estate renewal project that wins an estate ballot and meets these encouraged densities, unless there are exceptional reasons not to.

This is an edited section from Get London Building, Britain Remade’s plan to boost housebuilding in London and end the capital’s housing shortage. Read the full plan here.

Very interesting read. Which candidates are most likely to adopt these policies?

Fascinating read. I spent some time around the South Acton estate a few years ago whilst it was most of the way through redevlopment. It felt like it was being redeveloped for market rents or "affordable| (80% of market) rents whilst squeezing out council tenants. First, do you know if that is what went on on that huge estate? Second, what needs to be done to protect against squeezing out those who can't afford market or near market rents ?