The Super-Deduction

What to think about Rishi's radical corporate tax reform

For the past four or so years, I, along with Sam Bowman, Tom Clougherty, Pedro Serodio, Stian Westlake and a fair few others, have been making the case for a wonkish corporate tax reform called full expensing.

In short, it’s the idea that when businesses invest in new equipment or machinery they should be able to write this off from their corporate tax bill upfront just as they can do with other costs such as wages or energy bills.

This would be a big change from the status quo where long-lived assets have to be written off over a number of years. Why does this matter? You might think it’s just a matter of timing and that most businesses should be indifferent between being paid upfront and paid in instalments.

The main problem is that money has a time value. There’s opportunity cost – you could use that money to invest and make a return. That’s why banks can charge interest and have to pay interest to hold your savings. There’s also inflation to worry about too.

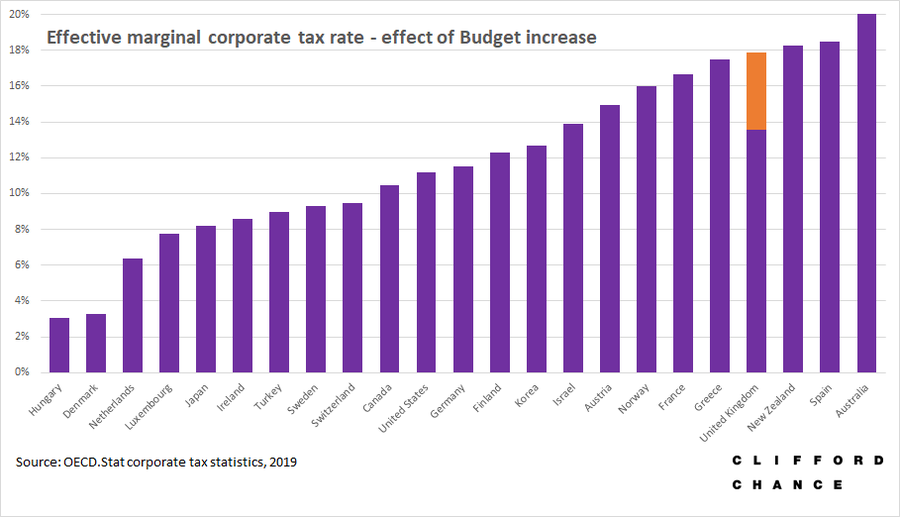

When Osborne slashed the headline rate of corporate tax, the tax rates that businesses actually paid didn’t change by much as he funded it in part by cutting capital allowances. For a while businesses couldn’t write-off investments in buildings at all. If Sunak had simply raised the headline rate to 25% then the UK would have ended up with one the highest effective marginal tax rates in the OECD. It’d be higher than France’s.

Thankfully he didn’t. He didn’t even announce full expensing. He went further. Full expensing would mean being able to deduct 100% of the cost today, but Sunak announced a 130% deduction, so you can deduct more from your tax bill than the investment actually cost. He called this the “super-deduction”.

Some thoughts:

Why was the super-deduction necessary?

The value of capital allowances are proportional to the rate. If the rate is expected to rise, expensing loses all or most of its benefit. Being able to deduct 80% of an investment’s costs from a 25% corporation tax bill might generate a bigger tax saving than being able to deduct 100% of an investment’s costs from a 19% corporation tax bill.

So by announcing the hike in advance, Sunak effectively created an incentive to delay investments. After all, it’s better to reduce your taxable income in higher tax years.

As Alan Cole pointed out 25 is close to 19 multiplied by 1.3 (130%). So if he announced full expensing instead, firms may have ended up with weaker investment incentives for the next two years. This whole problem derives from Sunak’s ‘honesty’. It’d have been better if he kept the 25% hike under wraps for the next two years.The cliff edge problem

When the super-deduction expires, we are set to return to the old system of capital allowances. As a result, the tax rate on new investments from 2023 onwards will be higher than under the status quo.In theory, this should create a massive incentive to bring forward investments acting as a powerful stimulus measure. In a sense, Rishi is counting on businesses to invest out of FOMO.

However, most investments take time to plan out. They also come in stages. I might build a new factory floor one year, fill it with machines the next, and then upgrade the line another year on. The problem is that if capital allowances are cut in the third year, it might affect the overall rationale for the investments in year one and two.

I suspect the latter effect dominates the former. If you look at the OBR’s forecast, investment is set to fall in the years after the super-deduction and is lower overall than forecast pre-pandemic. Rishi should have announced a move to full expensing when the super-deduction expires instead.

The fiscal costs are front loaded

I suspect one of the reasons why Rishi didn’t announce a move to full expensing when the rate rises to 25% was because he wanted to build up an evidence base. If investment spikes in the next two years, the revenue loss is an easier sell.

I predict that he will shift to full expensing when the super-deduction expires. A weird quirk of full expensing is that the fiscal costs are front-loaded because at the start you are deducting investments in full and still writing off assets invested in the years before. As the latter capital allowances are written down over time, the policy becomes significantly cheaper. When Pedro Serodio calculated the cost, he found that the fiscal cost fell by a quarter after two years and roughly halved after five.The accidental debt bias

As businesses can deduct debt interest payments letting them write off the costs of an investment in full could exacerbate the pro-debt, anti-equity bias in the tax system.

This has happened before when the UK had a system close to full expensing in the 1970/early 1980s.

“Prior to 1984, the headline corporate tax rate was set at 54% and businesses were able to immediately deduct the full value of investments in plants and machinery. As interest payments were tax deductible, debt-financed investments faced a negative effective marginal tax rate (up to -61.1%).”

This is a problem for two reasons. First, some types of investment are better suited to equity financing. For instance, risky entrepreneurial or innovative businesses are typically funded through equity. Second, it can contribute to excess leverage in the financial sector, increasing the chances of another financial crisis.

If full expensing is made permanent after the super-deduction expires then we’ll need to fix this. One option would be to flip the existing treatment of debt. Interest costs would become nondeductible but interest receipts would not be taxed. It would increase revenue by taxing returns on investments that might otherwise flow untaxed to tax-exempt or overseas entities.

What about intangibles?

This is where it gets a bit complicated. I’ve seen lots of people including Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation and Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies say that the new super-deduction favours investments in physical capital over investments in intangibles. This would be a big problem because half of investment is in intangibles and innovative tech businesses wouldn’t be able to benefit.

I’m not convinced they’re right. If you go on the Treasury website, they talk about qualifying plant and machinery investments. That sounds bad for intangibles, but there’s a hack.

You can use a tax rule to ‘make an election’, which allows you to treat an intangible as plant and machinery. This allows SMEs to use the Annual Investment Allowance to cover their website and software development costs.

Assuming the super-deduction works like the Annual Investment Allowance then it seems as if intangible investments qualify. I suspect the Treasury will clarify soon enough.What about buildings?

The super-deduction doesn’t cover structures and buildings, and is only 50% for integral features (e.g. lifts). In theory, there’s no reason why investments in buildings should face a higher tax rate than other business expenditures. Still, there’s reason to think the investments in buildings are harder to shift with temporary tax breaks. After all, it takes a while to gain planning permission and the like. It seems unlikely that you could get everything tied up on a new project in two years. The buildings that would have qualified for relief would have already been planned. In other words, it’d have no effect in shifting behaviour.

If we move to full expensing after the super-deduction expires then there’s a clear case for expanding to buildings. In the short term, we should increase the Structures and Buildings allowance. Freeports will apparently have a 10% SBA, the case for making that nationwide is strong.Effective Tax Rate ≠ Effective Marginal Tax Rate

The shift to a super-deduction is in effect a recognition that the headline rate isn’t the only thing that matters.

In theory, the super-deduction should reduce the effective marginal tax rate to zero. This is important because it directly affects whether or not a business will invest in one extra machine.

However, the tax rise will still have a chilling effect on foreign investment. Businesses will look at the effective average tax rate when deciding where to locate. If the UK’s EATR significantly then multinationals will be less likely to head quarter in the UK.

As Michael Devereux points out: “effective tax rates affect flows of foreign direct investment – and the evidence suggests a sizable impact. A consensus estimate is that inward foreign direct investment falls by 2.5% for every one percentage point increase in the corporation tax rate. Roughly, then a 4 percentage point rise in the tax rate would reduce inward investment by 10%.”

It’s also worth remembering that as the UK raises its headline rate, other nations are cutting theirs.

The US might reverse that trend slightly, but they’ll still have a much lower rate than they did in 2010.

Was it worth it?

If I delivered the budget yesterday, I would have done it differently. There wouldn’t have been a 6% tax hike. The super-deduction would have been merely full expensing and it would have been permanent. It’d also cover buildings too, and I’d have made sure there was no uncertainty over whether intangible assets qualify.

As it stands, we have two great years followed by a shift to a system significantly worse than the status quo.

Assuming Rishi does move to permanent full expensing from 2023, then whether or not it's worth the tradeoff is a tricky question.

I think it comes down to how you rank the relative importance of foreign direct investment and investment by firms already here. If it’s the former then we’re in a worse position post-budget. And vice versa.

But I’m optimistic. I think the pressure to keep headline rates low in light of international tax competition is strong and it’s more than possible future rises are cancelled or reigned back. On the other hand, the case for full expensing was hard-fought and it was far from guaranteed that we would get it. The salience of the super-deduction and a likely visible uptick in investment will also create the political pressure to extend.

By showing the stick that is going to be in use from 2023 it will have an impact on how those of us in Industry plan for the future. Sadly this Budget was as short term in its approach as so many previous ones. What I as someone trying to build a capital intensive part manufacturing business in the long term craves is a low tax rate and a long term stable approach to capital allowances. Where Osborne got it wrong was that initially he took away all allowances and then switched back and forth in the following years. So cut the number of rules and go for a simple system where CT is at 15% and allowances allow write off of plant and machinery over 4 years, buildings over 10 and land over 50, software and computer equipment and r & d can be fully expensed as they have limited second hand value. I would be prepared to wager that not only would the UK attract massive amounts of foreign direct investment but CT receipts would soar as it would be pointless trying to find ways round paying it.

Does anyone think we are actually going to 25% in 2023? Or is the realistic scenario that Sunak turns around next year and goes "well done chaps, great recovery, take 23% with 100% expensing as a well done".