What do higher interest rates mean for tax reform?

Full expensing: now more than ever

Budgets are typically dull affairs. In the flurry of press releases from think tanks, pressure groups and MP, one phrase usually pops up: “missed opportunity”. After last year’s Autumn Budget, Times business columnist Ryan Bourne counted 32 mentions (plus one ‘ducked opportunity’).

Friday’s not-so-mini mini-budget was an exception. Kwasi Kwarteng’s announcement of additional cuts to income tax and stamp duty on top of a massive energy market intervention and the cancellation of £38bn in tax rises prompted an altogether different response.

Yet as someone who agrees that Britain can and should grow faster, that believes tax rates can have large impacts on investment and labour supply, and is broadly sympathetic to the aims of Truss’s wider supply side reform agenda, I can’t help but feel it was a missed opportunity.

In terms of short-term growth bang for long-term fiscal buck, Kwarteng should have prioritised expanding capital allowances ahead of almost any other measure, but he didn’t.

Back in July, I set out what a plausible pro-growth leadership pitch on tax should look like. In short, use the limited fiscal space on offer to prioritise reductions in the taxes which have the largest negative impacts on growth. Specifically, I called for the next PM to increase investment by making the UK’s business tax regime the most competitive in the world. This would mean reversing the planned rise in Corporation Tax to 25% and improving the generousity of capital allowances.

We got the first, but the second was lacking. There was the cancellation of the planned cut in the Annual Investment Allowance, alongside positive announcements about enhanced capital allowances and targeted business rate reductions within investment zones. Yet Kwasi’s Growth Plan is unlikely to substantially shift the dial on investment relative to the pre-Budget baseline before the next election.

There are two problems.

1. Expectations

In 2020, when then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced that Corporation Tax would increase to 25% in 2023 he paired the measure with a 130% investment super-deduction to avoid a drop-off in investment. Yet, we are in a similar position today with a roughly two-thirds chance of a Labour-led Government in 2024 hiking the rate to 25%. Busineses are unlikely to make investment decisions, which may only yield profits in three/four years, based on a 19% rate they expect to be temporary. And this time there is no super-deduction. This is also the case with the abolition of the top rate of income tax. Who would relocate to Britain on the basis of a tax cut they don’t expect to last more than two years?

This isn’t to say that keeping the rate at 19% is a bad idea - it isn’t. But the benefits will only be realised if Truss can either win the election, or persuade Starmer not to junk it in two years time.

2. Interest Rates

Taxation affects investment, but no one seriously believes it is the only or even primary factor that determines investment levels. Factors such as aggregate demand, the availability of investment opportunities, and interest rates are as, if not more, important. But what is not always appreciated is that interest rates also affect the relationship between taxation and investment.

Corporation Tax affects investment in two ways:

The Average Effective Tax Rate, that is to say the rate businesses pay on average after accounting for all the various deductions and reliefs affects where firms choose to locate their investments.

The Marginal Effective Tax Rate, that is to say the rate businesses face on their last investment affects the level of investment a firm makes once they have decided to locate here.

Let’s focus on the latter. When a firm invests in new equipment, they incur an immediate upfront cost. Unlike other costs, such as wages, businesses cannot write the costs against their taxable profits immediately. Instead, they must deduct the costs over a number of years. Yet all of us would prefer to receive £100 today than £100 in five years for two reasons. First, inflation erodes the value of that £100 so it can no longer buy £100 worth of goods. Second, access to money today is valuable because it can be put to productive uses i.e. more investment. This is why we demand interest in return for putting our money in a savings account.

In a world where inflation is low and stable at 2% and market interest rates are at historic lows, the impact of forcing firms to write-off their investment costs gradually over time is low. A firm might discount £100’s worth of tax deductions received in £20 instalments to £76.

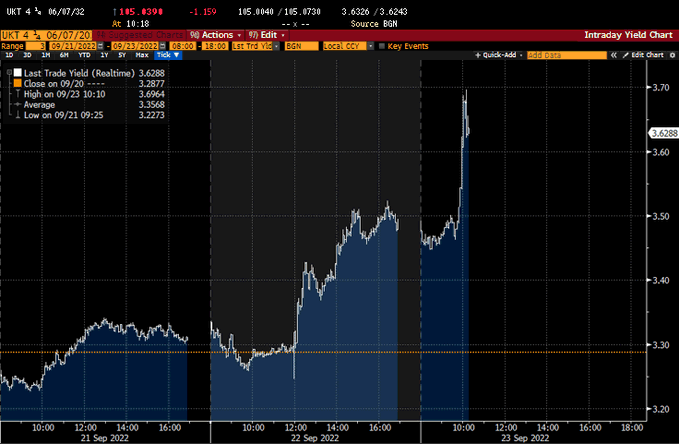

However, if interest rates or inflation jump up as they have over the past week then today’s £100 will be worth even less in five years time. The cost of waiting to write off an investment as it depreciates is much higher now. The marginal effective tax rate on investment has shot up.

For smaller firms who face higher interest rates, the extension of the Annual Investment Allowance, which allows businesses to write off up to £1m worth of qualifying plants and machinery upfront, will significantly strengthen the incentive to invest. But medium and large-sized businesses will face a new large tax disincentive to invest as a result of recent market moves.

In a way, this is similar to the current policy of freezing income tax thresholds and allowing fiscal drag to pull more taxpayers into higher rate bands. Inflation and its impact on interest rates mean that merely restoring the pre-covid status quo on corporation tax leaves us in a position where investment incentives are still substantially weaker.

I understand the political rationale for abolishing the Health and Social Care Levy and cutting the basic rate of income tax, but neither measure will bring us closer to 2.5% growth in the long-run because the labour supply response will be next to non-existent. And there won’t even be a short-term demand-side boost to growth with the economy close to capacity. Indeed, as I noted in my July post:

Inflation is high and does not appear to be purely transitory. Any additional borrowing will force the Bank of England to increase interest rates, which will dampen the growth benefits of tax cuts and hurt important parts of the Conservative’s electoral coalition.

Further tax cuts seem extremely unlikely in the wake of the past week’s market movements, but the case for expanding capital allowances either by moving to a system of full expensing (as advocated by the ASI, CPS, and many others) or creating a rate of return allowance (as the IFS called for in the Mirrlees Review) is stronger than ever.