Britain’s Problem with Planners

We don’t have enough and we ask way too much of the ones we have

One of Labour’s first moves to reform the planning system and get Britain building again was to immediately start work on hiring 300 additional planners.

This is a pretty uncontroversial move. Almost everyone, from developers to council leaders, agrees that Britain lacks enough planners to make our planning system work. Developers tell me that a lack of planning capacity within local authorities is now a major bottleneck to delivering housing. And if we’re going to build a fleet of new towns then we desperately need people to design the road layouts and determine where utilities should be placed.

No one could dispute that planning departments are overstretched, yet hiring more planners only solves one part of the problem. Britain has too few planners trying to do way too many things.

Let me give you an example. Planners in Peterborough recently recommended that a housing extension for an autistic child’s bedroom should be refused for a number of reasons. One of the reasons for refusal stood out to me. Planners stated that the extension should be refused because it would “leave little garden area for future occupiers.”

I can accept that it should have been refused for all sorts of reasons and I can see why a council might want to deter this particular property owner’s “ask for forgiveness, not permission, approach” to building an extension. But, a lack of garden space for future occupiers? Are you kidding me?

I’m old fashioned. I think that the state should only restrict what you can do with your own property when it has negative consequences for your neighbours or the public at large. It should mostly deal with what economists call externalities.

For example, if you want to build a very tall property that casts a long shadow on your neighbours garden such that nothing grows in it, then it is right the state steps in because you are imposing costs on others and not paying them for yourself.

But, “a lack of garden space for future occupiers” isn’t an externality. If future occupiers want garden space more than they want additional floorspace then they will pay the current owner less for it. In this case, the cost is completely internalised by the owner. If it turns out that prospective buyers agree with the planner's recommendation and value garden space over floor space, then the property owner will receive less money for their property.

And the Peterborough example isn’t an outlier either. In often-rainy London, most new apartment blocks must provide residents with a balcony. Whether you want a balcony or not, you will probably have to buy one if you want a new-build flat in London. What is particularly absurd about these rules is that many people find buildings bristling with large balconies ugly. We are mandating a fully internalised benefit that has an externalised cost!

It isn’t just balconies either. The London Plan has extensive rules around ‘thermal comfort’. Large floor to ceiling windows ‘should be avoided’ to prevent overheating. Dwellings should be dual aspect – with openable windows on two external walls. Dual-aspect is certainly nice to have, but the absurd fire safety requirement to have multiple staircases in any property at least 18 metres tall means that this requirement massively restricts the amount of floorspace developers can offer on a given plot.

Local plans are the biggest offender here, but not the only one. Stingy national building regulations insist that “the maximum window area of a building is fixed at between 11 per cent and 18 percent of its floor area.” The same rules ban sash windows altogether as they can only ever be 50% open, whereas the rules require that at least 55% of the window’s surface area must be openable. In theory, you can get around these regulations if you do expensive and complicated ‘dynamic thermal modelling’, but given the cost involved developers with tight margins just stick with the defaults. The regulations also insist that window sills be at least 1.1m from the floor due to the risk (and I’m really not making this up) that people might fall out on a hot day.

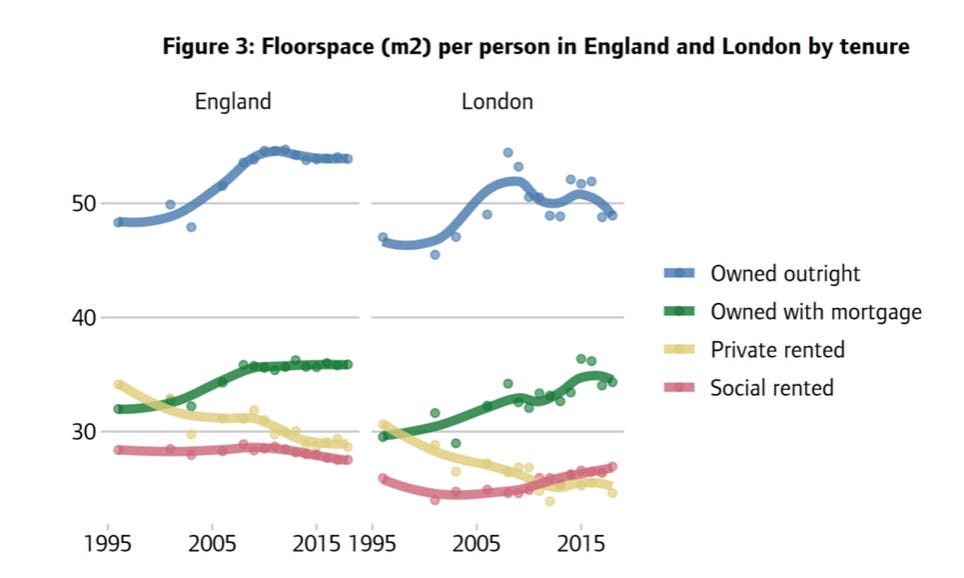

Here’s a more controversial example: minimum space standards. Planning rules don’t just dictate how a building looks or how big it is. They also dictate how much floorspace a dwelling must have. In London, a one bed flat intended for a single person must be at least 37sqm (a square metre is just over 10 square feet) big and one bed flat for two people at least 50sqm. There’s one problem. London’s persistent failure to permit enough housing means that today the average renter lives with just 25sqm, most often in flat shares and house shares.

The outcome is that almost no developer ever considers building a 37sqm one bed dwelling and house sharing for singles is effectively mandatory for all but the richest. Though n practice, some developers build co-living apartments, which the regulations don’t apply to. Ironically, apartments that would be illegal to build in London are frequently lauded by architectural magazines. And the problem isn’t just studios. There are also minimum rules on floorspace for two, three and four beds too.

For large developments, planners are tasked with figuring out the right mix of one-beds, two-beds, and so on. Developments can be refused for lacking enough family housing. In the absence of planning regulations, developers would almost certainly prioritise building one-beds. Our existing stock was built at a time when large shares of the population lived in the standard nuclear family. Later marriage, more childless adults, and more elderly people mean that a greater share of the population is looking for something other than a traditional family home. The real problem for families is that in the absence of a new supply of smaller one-bed properties, existing family homes are being subdivided and converted into Houses in Multiple Occupancy (HMOs) to compensate.

But for all the intense planning planners do with respect to new developments, broader economic impacts are often assumed away. The fact that a shortage of housing for single people leads to family homes being converted to HMOs is strangely neglected.

All of the above examples cover costs that are reflected in the final sale price. Homebuyers would, of course, pay more for brighter, larger properties with balconies. Yet, they may also choose to trade-off a bit less light or a bit less space or a balcony for cash. In most markets, we let buyers and sellers figure out these trade-offs for themselves. When it comes to housing, planners decide instead.

Planners add real value in many different ways, such as separating incompatible land uses, protecting communal space, mitigating overlooking, and blocking extremely ugly buildings that devalue others nearby by more than the amount of value they themselves create. Local coordination is also essential for ensuring efficient traffic flows, controlling heavily emitting and noisy vehicles, minimising the visual impact of bins, keeping the public sphere litter free, and so on. Where land ownership is unified, ‘private planning’ does exactly this, a phenomenon that John Kroencke has examined in his book on London’s Great Estates.

But, under the status quo, planners have to split their time between addressing market failures and second guessing the market. In an ideal system planners would spend less time on the latter – telling developers how best to satisfy their customers – so they can focus on the former – solving coordination problems – and actually add value. In other words, our planning system should be set up to deal with externalities but avoid paternalistic rules which try to second-guess what buyers and sellers want.

There are exceptions. Technically, the costs of a structurally unsound building are ‘internalised’. Yet, it is difficult for buyers to assess the structural soundness of a building until, well, it collapses. Regulation to address hidden costs that buyers cannot easily observe is completely legitimate. Both to protect buyers and to ensure that sellers aren’t incentivised to cut corners in hard to observe ways. Yet, the issues I’ve described above are not ones developers can conceal from buyers, in the same way faulty wiring or insulation can. You can easily see with your own eyes just how big a property is, whether or not it has any outdoor space, and whether or not its dual-aspect.

What would this mean in practice?

In almost every other market, the idea that the state should only intervene in voluntary transactions when there is a specific well-defined market failure, such as negative externalities or asymmetric information between buyers and sellers, is uncontroversial. We do not impose strict regulations on how comfortable furniture ought to be or mandate minimum storage levels for external hard drives.

But, applying this approach to land-use planning would mean big changes that go far beyond eliminating (or at least, heavily limiting) the rules I’ve mentioned.

Think of the example I mentioned around overlooking and light at the start. Imagine if instead of being a dispute between two separate property owners, the same person owned both properties. And for the sake of the point I am making, let’s pretend that no other property owner is affected by the choice to build up. The single property-owner now bears the full consequences of building one property high. In this case, overlooking and right to light would no longer be an issue for public planning.

The same applies to large developments more broadly. Many of the rules planners use to navigate disputes between households (e.g. rules around wall thickness for noise and setting minimum distances for back-to-back homes for overlooking) are no longer necessary when only other dwellings in the development are affected. All the costs and benefits are now internalised.

Sufficiently large developments should have essentially zero involvement from planners beyond their impact on things outside of the development.

You don’t actually need to have a single property-owner either. I recently visited a house with an outbuilding (a sort of office/shed thing). In theory, when an outbuilding is that close to a party wall, as it was in this case, there’s a requirement to seek planning permission, which can be expensive. Yet, the presence of a nearby outbuilding did not bother the affected neighbour who decided to look the other way.

In our ideal ‘market failure-based approach to planning’ world, not all neighbours would be as tolerant as my friend’s, they may instead request some form of quid-pro-quo. Yet many agreements between neighbours would be found and I suspect this could deliver a significant chunk of floorspace. In practice, this would require the creation of a new category of permitted development rights that can only be exercised if neighbouring parties consent.

In reality, it is rare that a single tall building only has consequences for one other property or that all the externalities associated with construction can be contained within a single-development. Finding an agreement between everyone affected would take ages and there would be large opportunities for holdouts to exploit the situation. It simply wouldn’t be practical. As such, there will still be ample opportunity for planners to add value.

Why would this system be better?

There are a few reasons.

Put simply, a planning system where planners focus on addressing genuine market failures while letting individuals and businesses figure out the rest would free up time for planners. We may still need to hire a few more planners, but a shortage of planners would be much less likely to be a bottleneck. A system where they can spend more time on what they’re best at, such as masterplanning, can’t be a bad thing.

But, there are deeper reasons to favour a system where planners ignore matters where costs are internalised.

Planners will never have access to the right information to decide for people: All planning decisions are about weighing up trade-offs. Rules of thumb can be useful, but every case is different and making the right call is contingent on all sorts of things. For example, what’s the right trade-off between space and thermal comfort? It almost certainly varies from city-to-city. When floorspace is at a premium, residents might prefer a larger single-aspect flat to a smaller dual-aspect alternative. The cliche ‘one man’s trash is another man’s treasure’ certainly applies to housing.

Planners lack the capacity to approve innovative solutions: Even when there is broad agreement on an objective (e.g. internal space, thermal comfort or privacy), it can be delivered in all sorts of different ways. Clever design can prevent overlooking without restricting density by setting minimum back-to-back distances. Using different materials or technologies can keep apartments at a comfortable temperature even in single aspect properties.

In theory, the discretionary nature of planning allows planners to approve creative solutions like the above. Yet, in practice, persuading a planner that you can deliver the same ends via different means is costly. The end result is less experimentation and less innovation.

Planners have an important role to play, but the Pareto principle applies. As in almost all professions, a small fraction of activities generate the most value. Our aim should be to free up their time so they can spend more time on those and less time on the other stuff.

Back in 2015 it was estimated that balcony requirements in Auckland added $40,000-70,000 NZD in extra costs per unit which is straight up insanity. And at least the weather is nice enough there that people might use them!

Section 106 planning gain obligations to force the building of 'affordable' housing is the most insane thing about a planning system that provides a lot of examples of insanity. Rather than actually freeing up the supply of housing so it is affordable for all (like bread), the supply is throttled and then a bribe is extorted from the economic rents received by developers.

Most houses that people actually want to live in were built before 1947, when the Town and Country Planning Act passed into law. Imagine if most people preferred to drive a car built in before 1947 rather than a modern one.

A large part of the problem with trying to legislate away any possible conflict with neighbours over externalities. If my neighbour wants to build a big rear extension, I might be unhappy, but there is no mechanism through which he and I can come to an agreement whereby I accept some sort of compensation, probably financial, for the loss of my amenity.

Coase pointed out that if the costs associated with coming to an agreement over this compensation were low, there would be a large social gain, and got a Nobel prize for doing so. Sadly, no town planner has ever heard of Coase, or, frankly has any understanding of economics whatsoever.