Can Labour build 1.5 million homes?

Grading Labour's housebuilding plans.

In a previous post, I looked at Labour’s plans to make it easier to build infrastructure. In this post, I look at another plank of Labour’s plan to get Britain building again: building 1.5m homes.

If the polls are to be believed, Labour are on-course to win a massive majority. Unless there is a catastrophic polling error the likes of which we have never seen before in British politics, Keir Starmer’s Labour Party will shortly enter office with an unprecedented mandate to reform the planning system to get more homes built.

Labour’s rhetoric in the run-up to polling day has been uncompromising. Keir Starmer has run toward controversy talking up a willingness to ‘make enemies’ and ‘take on the NIMBYs’. Sir Humphrey might describe Sir Keir’s decision to call for building on the green belt as ‘very courageous’, yet Starmer has gone out of his way to highlight a policy that conventional political wisdom tells us is a vote loser in the South East marginals that decide elections.

There’s a simple reason why. Britain’s fundamental problem is productivity. Productivity has been stagnant in Britain for over a decade and Brits produce less per hour than their French, German, and American counterparts. At the centre of Britain’s productivity crisis is a shortage of housing. High housing costs price workers out of Britain’s most productive places. When a worker moves from Britain’s least productive region to Britain’s most productive region they experience a sizable pay bump – 17% in fact. The problem is that these moves often don’t take place because high rents eat away that pay bump.

Labour really do get this point. Take this paragraph from their ‘Power and Partnership’ document, probably the most detailed document out there on Labour’s economic plans.

“By getting Britain building again, Labour will make housing more affordable and give working people more control over what they spend their income on and where they choose to live. Nobody should be locked out of pursuing new opportunities, taking up a job they love or moving to a new city by high housing costs.

“Nor should workers in our biggest cities see the lion’s share of their paycheque disappear every month to spiralling rents and mortgage costs, cancelling out the benefits of high productivity for all but the very highest earners or the already fortunate.”

As far as the analysis goes, it is spot on. But do Labour’s plans for housebuilding match up to their bold rhetoric?

In fact, Labour are promising fewer homes over the next Parliament than the Conservatives (1.6 million) and the Liberal Democrats (380,000 a year).

Labour may want to under-promise and over-deliver. It’d make a change from under-promising and under-delivering, which is the status quo in housing. Labour might also be concerned about getting housing numbers to recover from their recent collapse first. Recent reports suggest Labour hope to deliver the lion’s share of the 1.5 million towards the end of the Parliament. This would imply an annual house building rate well above 300,000.

300,000 homes per year has a special resonance in British politics. In part, because it’s the figure cited in New Labour’s Barker Review, but also because it has made political waves before.

At the Conservative Party Conference in 1950, delegates famously demanded a higher housing target going so far as to chant “Three hundred thousand!” at party chairman Lord Woolton. Woolton popped off stage to ask the head of the Conservative Research Department if it could be done and then promptly announced a new 300,000 home target on stage right then and there. A year later they were in office.

Yet, the truth is while 300,000 a year is the bare minimum to improve affordability. It will take a long time, half a century in fact, to make up the country’s 4.3 million home backlog at this rate. To really make a dent in affordability, Labour need to be aiming much higher. The Centre for Cities suggest 442,000 homes per year is a more appropriate target, while property researchers Bidwells have recently called for a 550,000 home annual target.

This might seem high, but by international standards it really isn’t. For example, Tokyo alone builds around 142,000 homes per year (more than twice as many as us on a per capita basis), while Houston has permitted around 550,000 homes in the last decade, equivalent to 450,000 per year on England’s population. Nor is it unprecedented by historical standards either. When housebuilding boomed in the 1930s, our population was around 30% smaller. It’d be the equivalent of around 420,000 homes a year with today’s population

Yet, national targets are worthless without policies underneath to ensure they are actually hit. So what are Labour’s policies?

Targets

Labour’s conversion to YIMBYism came swiftly after the Conservatives scrapped mandatory housing targets in late 2022. The impact of Sunak’s decision to drop mandatory targets in the face of a backbench rebellion has been unsurprising to anyone acquainted with our planning system. Local authorities typically lack a good incentive to approve new housing so they consistently underdeliver. What mandatory housing targets do is they force local authorities to have a plan in place to meet them, and if they don’t have one in place or they aren’t hitting at least 75% of their target over a three year period, a presumption in favour of sustainable development applies which makes it much harder for the council to reject a given project.

Removing the only part of the system that forces local authorities to actually plan for new development had the inevitable result of less housing being permitted. In fact, since the changes more than 60 local authorities have withdrawn or paused their local plans and there are even cases of councils overturning past planning decisions.

Labour have pledged to bring back mandatory housing targets and give them more teeth. Labour’s approach is framed as giving local leaders a say over ‘how’ housing is delivered, but not a say over ‘if’ housing is delivered.

Under Labour’s plans, local authorities that fail to meet their housing requirements, or lack a valid plan, would once again be forced to accept development. But even when a valid plan is in place developers regularly complain about proposals getting rejected despite following it to a T. So for local authorities that do have a valid local plan in place, there’d be a new strong ‘presumption in favour’ of development for any proposals that conform to the local plan. This essentially gives developers a much stronger chance of being successful if they choose to challenge a council’s planning rejection in court. This, in turn, means councils are much more likely to say yes.

On top of this, Labour have also committed to instruct planning inspectors to rewrite local plans when local authorities consistently fail to deliver enough homes.

None of this is radical, but it will help get homes built at the margin. There are some issues that need to be thought through though.

First, the impact of removing mandatory housing targets on supply may have been felt swiftly, but it will take a while for reinstatement to pass through into housebuilding numbers. Councils will almost certainly be given time to develop local plans and the stronger presumption in favour of sustainable development is unlikely to bite immediately.

Second, it is reliant on consistent political will from the centre. If Labour’s polling drops in years two or three of the next Parliament (as is usually the case) will they still be willing to force housing on local authorities in marginal seats? It is worth noting that, under Boris, the Conservatives tried to beef up housing targets only to be forced to climb down. Labour’s absurdly efficient vote where a really large number of MPs could be elected on extremely thin majorities could cause problems down the line. Expect backbench rebellions on housing closer to the next election.

Third, there’s a question about what the housing targets actually should be. One problem is that as they stand they overweight things like population growth forecasts, which are themselves based on past trends. This creates an obvious problem because population growth is a function of affordability. Cheap housing entices people to an area, expensive housing drives them away. As a result, housing targets understate need in the areas where need is greatest.

Fourth, related to this, is the question about the urban uplift. As of 2020, policy raises targets in the country’s 20 largest urban areas by 35%. Applying the urban uplift to London commits the capital to an almost 100,000 homes a year target. The uplift’s creation may have been somewhat cynical – Conservatives tend to be less competitive in urban areas – but it has a strong economic and environmental rationale. Will Labour keep it?

Grey Belt

More radical is Labour’s plan to release more Green Belt land for development. Labour have pledged to build on what they call the Grey Belt. Most Green Belt land, even that which doesn’t have ‘national landscape’ designation, is rather beautiful, but that’s not always true.

You see the Green Belt isn’t actually a nature protection policy. It’s an anti-sprawl policy. As a result, there’s actually a fair amount of it that’s not beautiful at all and is in fact, rather ugly. Labour calls the Green Belt’s car washes, parking lots, and wasteland the Grey Belt.

How much Grey Belt is there? Quite a lot actually!

Architect Russell Curtis has been developing an AI tool to identify Grey Belt land. He’s yet to publish his full findings but he has identified 770 hectares of it around St Albans alone. Wider industry estimates suggest that between 100,000 and 500,000 homes could be delivered on Grey Belt land.

Not all bits of Grey Belt are appropriate for development and Labour have a tough set of criteria (golden rules) on when building is acceptable. Developments must target 50% affordable, come with new infrastructure like GP surgeries, and hit a higher level of biodiversity net gain.

Labour’s proposal on the Green Belt isn’t as radical (or for my money, environmentally beneficial) as other proposals. For example, Paul Cheshire and Boyana Buyuklieva’s proposal to permit building on non-environmentally valuable land within 800m of commuter rail stations with fast and frequent connections to major city centres would certainly unlock more homes – 2 million in fact. Labour likely judges that allowing development on intensively-farmed fields as well as wasteland is a step too far.

What about Labour’s golden rules for housing? There is a decent rationale to Labour’s requirement for infrastructure and affordable housing. Land values in the Green Belt are typically low, but can multiply by 100 times when planning permission is granted. However, it could backfire if enforced too strictly. Loading obligation after obligation onto ‘Grey Belt’ projects will make some projects unviable. That’s especially the case for developments on really ‘grey’ plots that require decontamination in some way.

Negotiating levels of affordable housing, designing biodiversity schemes, and providing infrastructure can slow developments down and make life harder for smaller developers. A better solution would be to charge a flat tariff (say 20% of the sale value) and let local authorities spend it on their priorities whether its access to open green spaces or new council housing.

Labour talk dismissively of “expensive executive homes local people can’t afford”, yet it is worth remembering that in their absence wealthy home buyers would be bidding up other properties. Study after study (summarised here by the GLA’s James Gleeson) shows that when developers build market-rate housing – I refuse to use the BS marketing term ‘luxury home’ – it frees up properties at the lower end of the market improving affordability for all. Affordable housing requirements merely short-circuit this filtering process at the cost of making it harder to deliver new homes.

New Towns

Labour’s other big plan is to create a new generation of new towns. This is arguably Labour’s most eye-catching proposal and it will almost certainly be the hardest one to deliver well. Labour have pledged to announce a list, chosen by independent experts, within 12 months of being elected.

Where will these new towns be and what will they look like? Labour have given hints through their ‘New Towns Code’. High levels (40%) of social and below-market value housing are one key feature. Another is tree-lined streets and the popular design styles advocated for by groups such as Create Streets. In terms of location, Labour reference garden suburbs, public transport links, and areas with significant housing need.

There are successful examples of new towns with strong local economies. Milton Keynes, with its fast connection to London Euston, is one. Stevenage another (also with fast connections to London’s centre). Yet, there are failures too.

Skelmersdale near Liverpool lacked good transport connections (incredibly their rail station closed 5 years before they became a new town) and failed to attract employers. Poverty levels there are unacceptably high.

Northstowe near Cambridge, the largest new town in Britain since Milton Keynes, has more going for it on paper. It is a short commute from Cambridge’s hot job market. Yet, it’s widely seen as a failure. Six years after people have moved in there is still no local shop, GP surgery or cafe. A recent BBC article describes it as a ‘new town built with no heart’.

New Towns aren’t quick projects either. Building the relevant infrastructure takes time and planning issues can cause major delays. Take Ebbsfleet, a new town on the High Speed 1 line to St Pancras. While it has more of a ‘heart’ than Northstowe, nowhere near as many homes as originally envisioned have been delivered. Major parts of a redevelopment plan to build a large theme park and housing had to be curtailed when a large area was designated a site of special scientific interest.

Labour have stated an intention to deliver at least some homes in new towns by the end of the parliament, but even under a best case scenario new towns won’t be seriously contributing to housing supply until at least five years time. Restoring mandatory housing targets and building on the ‘Grey Belt’ will be doing almost all of the heavy lifting for Labour this Parliament.

New towns should be built where people want to live. That means new towns should be built in places with fast connections to existing jobs. In some cases, this could mean an entirely new settlement built around a rail connection to London or Oxford. But, it could also mean New Town not in the sense of Milton Keynes but in the sense of Edinburgh New Town. That is to say, well designed urban extensions to existing successful settlements.

Michael Gove’s plan to build a new science quarter in Cambridge is a good example of this. Labour should take this proposal, in many ways our most developed new town proposal, and accelerate it. Likewise, there’s strong cases to expand Oxford, York, and Bristol in similar ways too. It should be noted that when other countries build ‘new towns’, they usually take this form.

What else are they offering?

On top of targets, grey belt, and new towns, Labour have also pledged to deliver a housing recovery plan, “a blitz of planning reform to quickly and materially boost housebuilding”, within 100 days of getting elected.

Labour are yet to set out in detail what this will mean in practice beyond talk of a ‘Brownfield Fast Track’, but recent reports in Bloomberg that Labour have already instructed lawyers are promising.

One option would be to take advantage of the National Development Management Policies (NDMP) powers created by the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act. This would allow DLUHC to set national standards in areas where different councils take widely different approaches. For example, some councils take an extremely strong line on embedded carbon, setting extremely high carbon prices for demolitions. This is almost certainly the wrong level of government to do climate policy at and merely creates unnecessary bureaucracy. Using the NDMP powers to simplify and standardise things would be one way of speeding up the planning process and creating certainty for developers.

Labour have also talked up a return to regional strategic planning, but are yet to set details out beyond talking up a bigger role for Mayors. In theory, directly elected mayors should face fewer anti-development electoral pressures than ward councillors, yet the track record for mayors on housing is mixed. In both Manchester and London, Mayors have used their powers to take hard anti-development lines on the Green Belt.

One case for granting more powers to Mayors is transport-oriented development – building new housing around existing transport routes, and planning for new homes alongside new transport infrastructure. At the moment, a combined authority like West Yorkshire could design a tram route, but wouldn’t be the ones in charge of planning housing around the tram stops.

Labour also pledged to hire more planning officers (300 in fact) funded by a higher rate of stamp duty for foreign home buyers. There's definitely an issue with planning departments lacking the resources to deal with applications in a timely manner, but higher rates of stamp duty (the most damaging tax there is), even if they only apply to foreign buyers, are not a good way to fund further spending.

What’s missing?

There’s a lot to like here and I think it’s completely plausible that Labour hits its 1.5 million home target for the Parliament. But I can’t help but feel they’ve missed a couple of tricks.

Labour mentions ‘regeneration’, but there’s little mention of how renewing our post-war council estates can deliver upgraded homes for existing social tenants, cut council housing waiting lists, and get more market-rate private homes built. This isn’t solely a planning issue – councils and housing associations have major capacity issues – but planning policies can help by allowing projects to reach the high densities that make it possible to deliver a big boost to the social housing stock.

In Power and Partnership, Labour talks about using 1.5m new homes to increase the ‘effective size of our major cities and high-potential towns so that they can reap the benefits of scale and agglomeration needed to develop and cement their labour market clusters’. This is exactly the right way to use planning reform to drive economic growth, but Labour’s plans are pretty quiet on what they’re going to do in cities.

Contrast Labour’s plans with the Conservative Manifesto. The Tories have pledged to create “a fast track route through the planning system for new homes on previously developed land in the 20 largest cities” and to raise “density levels in inner London to those of European cities like Paris and Barcelona.” Now, it is completely reasonable to be sceptical of the Conservatives’ ability to deliver on this front after 14 years in government and detail is lacking, but the real prize of planning reform is densifying high-growth cities like London.

Not only because it is the best way to allow people to access good jobs, but because it is the green option too. Cities are green and emit less carbon per person than sparsely populated areas. Yet, in many of our most productive cities, land near train stations is built out at extremely low density levels by European standards. Changing that by building more homes near good transport links in places like London is the most pro-growth net zero policy there is.

Labour may hope to do this via targets. Leaving it up to the Mayors and councils of big cities, almost all of which are now Labour, to figure out the ‘how’. Yet, too often our cities under-deliver and block good projects. Take Brighton’s Labour-run council blocking almost 500 homes on the site of an old gasworks. Or the Mayor of London dragging his feet on the 500-home Bishopsgate Goodsyard Development with an eight year gap between the first planning application and planning permission being granted. Labour-run Hackney council opposed the proposals every step of the way. One issue in London is that the London Plan is so complicated that it is genuinely difficult for developers to figure out whether or not their project is actually compliant.

To get more homes built in the places where they are needed the most, Keir Starmer should look at the approach of another Labour Prime Minister: New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern.

New Zealand passed a series of reforms to make it much easier to redevelop land near rail stations, busy bus routes, and city centres. In these places, housebuilders get automatic planning permission for any project up to six-storeys high. This kind of gentle intensification has delivered a lot of homes already.

In Auckland, New Zealand’s biggest city, a precursor policy kept rents down. In fact, one study found that rents were a third lower than they otherwise would have been as a result of the policy. A similar fall in London rents would mean a £6,000 saving for the average couple.

Back in 2019, Sadiq Khan proposed a version of this policy. If implemented, it would have created presumption in favour of development on small sites within 800m of railway stations and town centres. The policy did not apply to conservation areas, to new buildings ten-storeys or higher, and insisted on no net loss of green space. Borough councils would have been required to draw up area-wide design codes to ensure developments were in keeping with local areas. The policy was eventually dropped after the Planning Inspectorate decided this approach was ‘too far, too soon’.

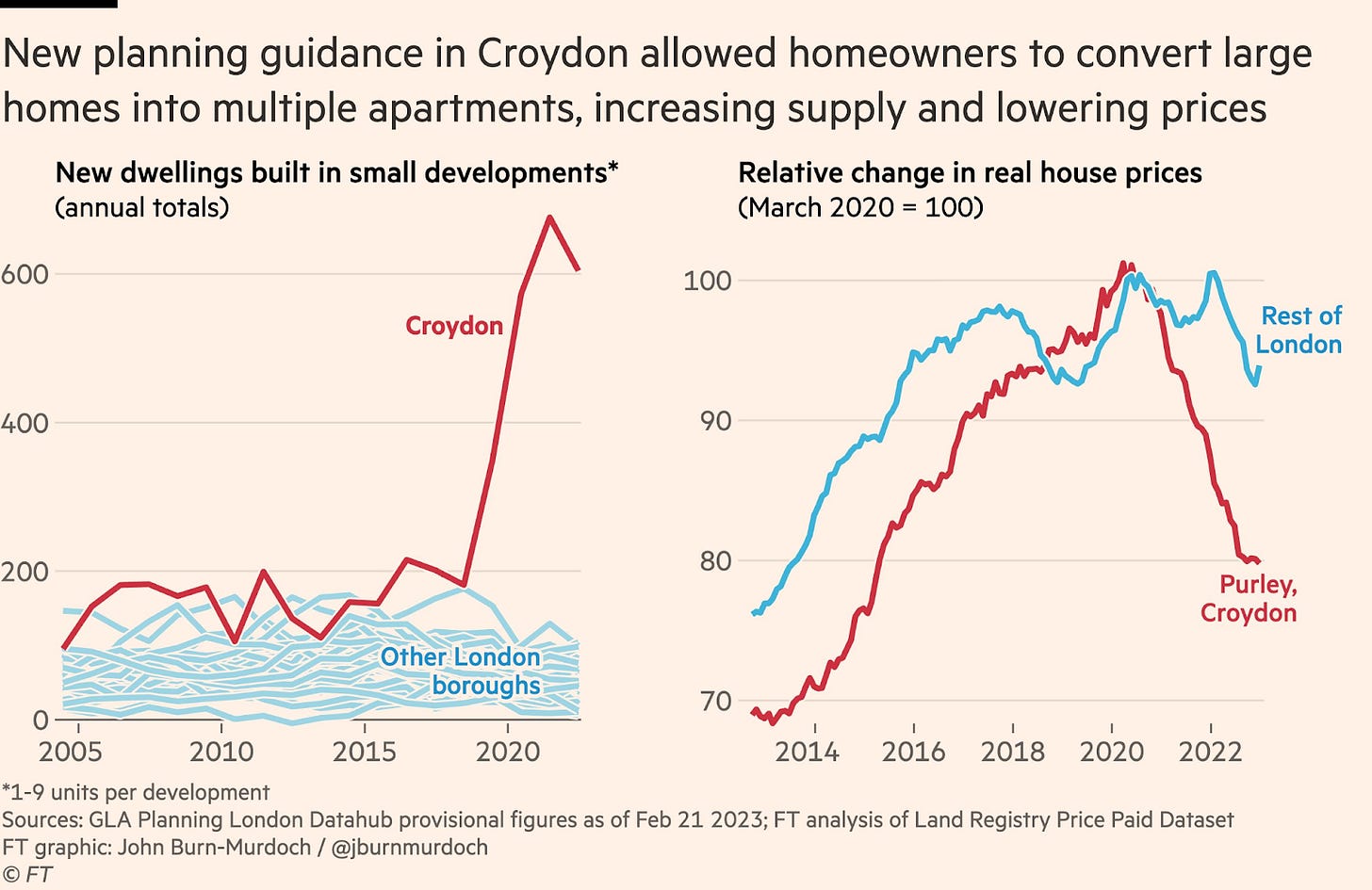

Yet, this is a proven way of swiftly boosting supply. Croydon, for example, adopted a Supplementary Planning Document that encouraged suburban intensification on small sites near train and tram stops. It had a big impact on supply and prices.

If Labour want to boost supply quickly and get homes built in the right places, then they should complement their Grey Belt and New Towns plans with a Kiwi-style freedom to build near transport links.

In Britain Remade’s plan to get Britain building, we propose a version targeted at high housing cost areas. Using new National Development Management Policy powers, the next Housing secretary should create an overwhelming presumption of consent for new six-storey developments within walking distance of stations and business hubs in cities where house prices are more than 7.5 times local incomes and housing targets aren’t being met. To make sure this policy sticks, they should be required to meet three key conditions:

There should be no net loss of green space.

All new housing should be built to the highest energy-efficiency standards feasible and offer low-carbon heating options.

All new buildings should be built to a design code developed with local people getting a real say on design.

Labour will enter office with a unique mandate to tackle Britain’s biggest economic problem. Their mandate won’t last forever so it is crucial they hit the ground running. Reinstating (and beefing up) housing targets, building on the ‘grey belt’, and, if done right, developing entirely new towns will all meaningfully boost supply throughout the next Parliament. But, if they want to boost supply quickly and get homes built in the most economically impactful places, they need a NZ-style policy to make it easier to build homes in the best connected parts of our most productive cities.

I think the failure of Northstowe & other Cambridge developments (Cambourne, the further parts of Trumptington) are that they try to combine being an urban expansion with a new town. If 95% (not really, but the vast majority) of people are meant to be travelling into a bigger city, then there is a pretty low incentive for a lot of community structures. However, these are also too far away from Cambridge for there to be a sort of "community spillover" (i.e., people using non-essential facilities due to the Cambridge ones being too busy). I will say that both Cambourne and the further parts of Trumpington seem to have experienced what feels a similar lack of sort of "secondary" spaces as Northstowe, although luckily nowhere near as acute as in Northstowe. Cambridge is not of the size to spawn sort of cities-within-cities, like comparable rich places like London. It is an amateur's view, so I have no evidence other than general "vibes" of each of these three places. I think lessons to be learnt from this are to use the airport (closer in), increase public transport, and angle for a new town somewhere around Stansted (a new village is already being developed there).

No.

Next question?