How to Get London Building in the right places

What London can learn from Houston and Auckland.

In under a month, Londoners will go to the polls to decide whether Sadiq Khan deserves another four years in post. The Mayoral election will be fought on a number of issues from ULEZ to knife crime, but one issues stands out dwarfing all others: housing.

London is suffering from a brutal housing shortage. The stats speak for themselves.

In London, house prices are now 12.5 times average earnings.

To save enough for a deposit on an average London home would take a couple earning an ordinary wage more than 30 years.

Floor space per person for London’s renters has fallen to just 25 square metres.

In fact, a one bed in London is more expensive than a three bed in any other part of the UK.

Londoners earn around 15% more than the national average. But after you take into account housing costs Londoners only take home 1% more than people around the rest of the UK

All of this is because we have failed to build enough homes to keep up with demand. For every 10 jobs London has added in the last decade, the capital has only built three homes.

It wasn’t always like this. In the 1930s, London built 61,500 homes each year. In some years, London built more than 70,000 homes, but we haven’t built anywhere close to that many since WW2.

To bring down sky-high rents and restore the dream of home ownership, meeting and beating London’s pre-war house building peak of 80,000 per year should be the aim. Yet aiming high is not enough — ambitious targets have been missed time and time again. Whoever wins the next Mayoral election must have a clear plan to deliver it and Get London Building.

But if they don’t have one, they can borrow Britain Remade’s. Get London Building sets out our practical plan to tackle the capital’s housing shortage by:

Renewing damp and cold post-war estates, building warmer homes for existing residents and local people.

Building more near stations to shorten commutes and tackle climate change.

Putting London's golf courses and industrial land to better use to provide Londoners with homes and new green spaces.

In the run-up to polling day, we’ll be re-posting the key sections on this Substack.

To kick us off, here’s how we can cut rents and emissions by building up near tube and railway stations.

Build More in London’s Best Connected Areas

London’s failure to build anywhere near enough homes to keep pace with job growth is not just an economic and social problem – it is an environmental problem too.

Cities are green. People living in cities emit 50% less carbon than people who don’t and Londoners emit less carbon per person than people in any other part of Britain. There’s a simple reason why: London is by far Britain’s best connected city. Every day, Londoners make more than 10 million journeys on TfL’s buses, tubes, and trains, while only 42% of London households own a car.

Transport isn’t the only reason that Londoners’ carbon footprints are smaller. Londoners are more likely to live in flats or terraced housing, which use less energy than a detached suburban home. In fact, purpose-built flats use around a third of the energy a detached house does because shared walls cut heat loss.

Making it easier for more people to live in places with good transport connections allows us to boost growth and cut emissions at the same time.

Yet Paris, Madrid, and Milan all have areas that are more than twice as dense as the densest part of London. Worse still, some of the best connected parts of London, where owning a car is a choice rather than a necessity, are built at extremely low densities. Even in Zone 1, it is not uncommon to see streets where not a single house is taller than three storeys.

Enhancing heritage, cutting emissions, and supporting families

Some of London’s densest parts are also some of its best-loved. Think of the rows of six-storey terraces and mansion blocks in Kensington, Maida Vale, and Bloomsbury. The same is true of the apartment blocks of Hausmann’s Paris and Cerda’s Barcelona, and of the tenement houses of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

It is possible to build up and enhance London’s heritage. For example, a forward-thinking move by the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea allowed a row of terraced houses in a Conservation Area to add an extra mansard floor without applying for planning permission so long as they were in accordance to a local design code and built with solar panels on top.

Imagine what would be possible if this approach was applied across London. Create Streets estimate that if just 10% of the 4.7 million pre-1919 homes in England added mansard floors, it would create almost a million new bedrooms without a single demolition being necessary. As a fifth of all of England’s pre-1919 homes are in London, this suggests 200,000 new bedrooms in London assuming the same uptake. Not only would this allow more people to live and work in London, but the property value uplift would help homeowners to fund ambitious retrofits that would be otherwise prohibitively expensive. The Mayor of London should set a clear policy in the London Plan to permit mansard extensions. The policy should specify that Grade II listing or Conservation Area status should not prevent additions, where there was a local tradition of mansard construction when the building was erected and it enables retrofits on otherwise hard-to-decarbonise buildings.

Gentle intensification along similar lines can help meet London’s need for more family homes. In South Tottenham, Haringey councillors worked with community leaders to tackle extreme levels of overcrowding affecting the Hasidic community, where a lack of large family homes in the area meant that many families had children living four to a bedroom. Haringey Council implemented a policy allowing Victorian terraced houses to add 1 and half storeys subject to a strict and detailed design code that ensured extensions were in keeping with the area's heritage. As the policy was aimed to tackle overcrowding and support large families, it did not apply to Houses in Multiple Occupancy (HMOs). Analysis by Create Streets found that 200 properties (out of total 1,000 affected) took advantage of this new freedom. The Mayor should extend the South Tottenham approach across London and empower homeowners. The Mayor can do this by creating a presumption in favour of development for sympathetic single-storey upward extensions when they are in keeping with the building’s original designs and improve the building’s energy performance.

More homes in the right places

New Zealand offers a model for how London can cut emissions and get more homes built. In 2020, Jacinda Ardern’s government forced six major cities to allow more housing. The new rules required councils to automatically approve any building up to six-storeys within walking distance of the city centre, commercial hubs or rapid transit stops. The rules also banned councils from forcing new developments to have a minimum level of parking. It is too early to assess the impact of this policy, but the number of new homes built from a similar Kiwi policy in Auckland bodes well. The Auckland Unitary Plan, which passed in 2016, doubled housebuilding in the city and shifted where new homes are built away from sprawling car-dependent suburbs to existing built-up areas with good public transport connections.

What was the impact of Auckland’s housebuilding boom on ordinary people? A recent study found that rents were a third lower than they otherwise would have been due to the reform. Think about that – a third lower: if the same happened in London rents, it’d be a £6,000 saving for a young family renting the average two-bed.

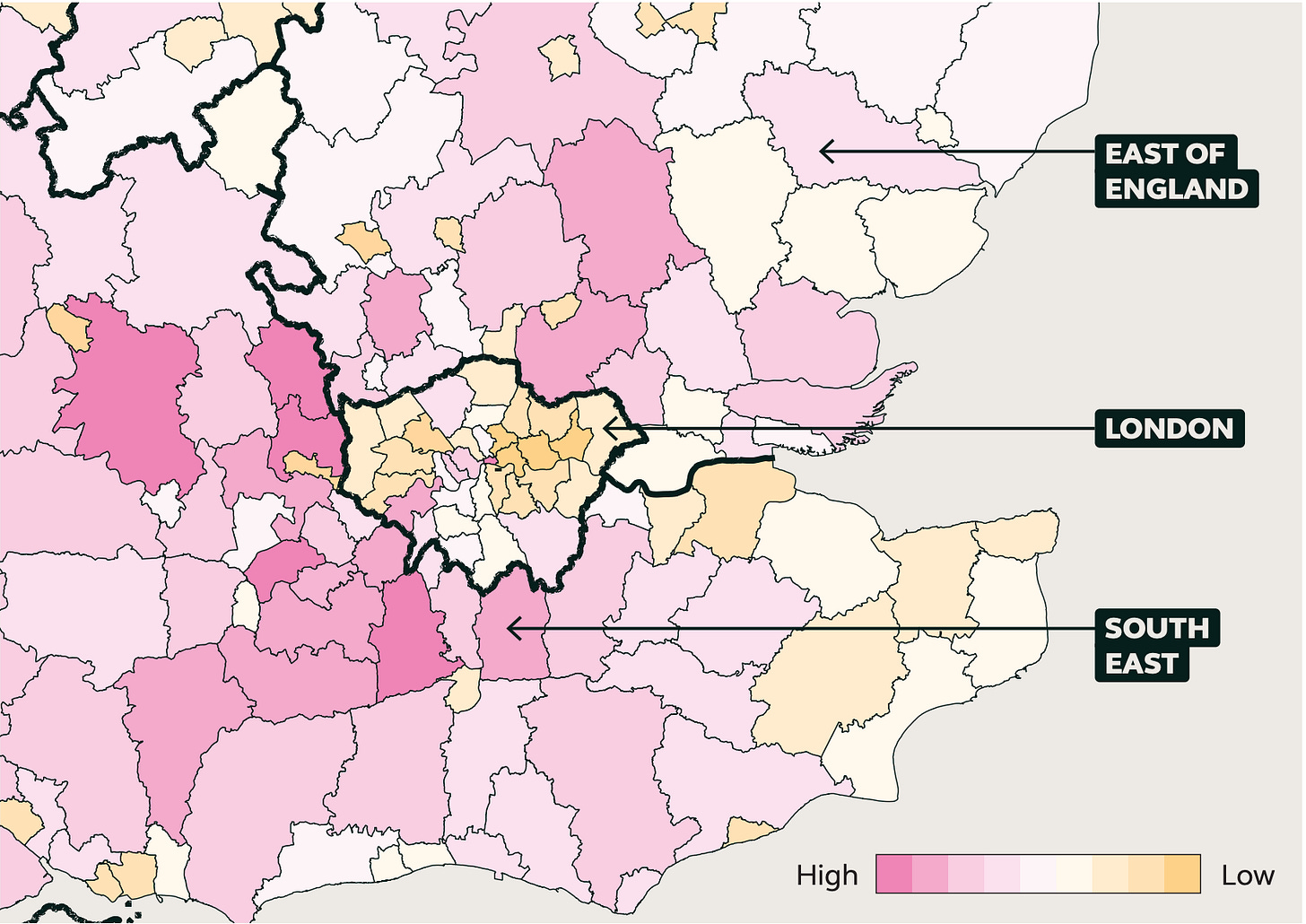

London should follow New Zealand’s lead. The Mayor should rewrite the London Plan to explicitly allow up to six-storey developments near the capital’s best connected sites. The next London Plan should resurrect a modified version of the Small Sites policy proposed in the Draft London Plan 2019. The policy proposed a presumption in favour of development on small sites within 800m of a railway station or town centre, or was otherwise well-connected. The policy insisted upon no net loss of green space (a ban on so-called ‘garden grabbing’), did not apply on heritage sites, and did not apply to buildings more than 10 storeys tall. It also required that boroughs insist on area-wide design codes to ensure developments are attractive.

If implemented by the Greater London Authority it could have boosted London’s housing supply by at least 25,000 homes a year. Yet, the policy was dropped after Planning Inspectors intervened arguing the approach was “too far too soon”. London’s persistent failure to deliver enough homes, the drop-off in supply from large developers (in response to higher interest rates and uncertainty around new building safety regulations, such as second staircase rules), and stronger green belt protections in the NPPF should prompt a rethink.

Unlike complex large brownfield sites, small sites can be built by small local builders supporting local employment. Crucially, unlike large sites, small housebuilders do not have to worry about holding back properties to avoid flooding the market – simply put, they get homes to market quicker.

To allow more people to live near the best connected parts of London, the Mayor should include a new Small Sites policy in the next London Plan. There should a clear and strong presumption in favour of development provided it meets the following conditions:

it is no more than six-storeys (plus an additional mansard floor, where appropriate) or the average height of a street, whichever is higher;

it is within walking distance of tube or rail station, or is otherwise extremely well-connected;

all redevelopments and extensions must significantly improve energy efficiency by including solar panels or low-carbon heating options such as heat pumps, where appropriate. This requirement does not apply to extensions to buildings that have already seen extensive efficiency upgrades;

the site is no more than 0.25 hectares in size and less than 25 units;

it is not on Green Belt land and there is no net loss of green space;

it is built to a design code developed in consultation with local people that pays care to the architectural heritage of London.

To alleviate fears that it will lead to ‘too much, too fast’, the London Plan should permit individual streets to opt out of the policy for a 20 year period when 75% of households choose to do so. Houston, Texas adopted a similar approach when it densified its urban core. While some neighbourhoods opted out, the policy still led to the construction of an additional 25,000 new homes and helped Houston keep rents low.

Producing design codes for London’s diverse architectural traditions is an innately hard task and with local planning departments experiencing significant cuts over the past decade, there are questions over delivery. To ensure that this Small Sites policy creates beautiful and popular new homes, the Mayor of London should work with the Government’s new Office for Place to develop a Design Code toolkit for London’s borough.

One key barrier that small builders face is the rising cost of preparing a planning application. Across the UK, the share of homes delivered by SMEs has fallen from four in ten in 1988 to one in ten now. At the same time, navigating the planning system has become more expensive and complicated. Lichfields estimate the cost of getting planning approval for a moderate development has, adjusted for inflation, risen fivefold to £125,000. Lichfields report notes that “validation lists now typically stretch to 30 separate assessments, and come with guidance notes that can exceed 100 pages.”

To reduce the amount of red tape that SMEs face, the Mayor should strongly encourage local authorities to implement Local Development Orders (LDOs). Under this model, development is automatically approved as long as it meets strict conditions set out in the LDO. Where boroughs have failed to meet their housing requirement under this policy despite having high potential for density, the Mayor should use Mayoral Development Orders to eliminate unnecessary bureaucracy for small builders.

In the future, when boroughs benefit from new transport infrastructure such as new stations or receive more frequent services due to network upgrades, the Mayor should require boroughs to produce Local Development Orders that deliver higher levels of density. If boroughs LDOs fail to fully realise the opportunity for new homes then the Mayor should intervene directly and use Mayoral Development Orders.

There is a massive opportunity to meet London’s housing need and cut emissions through gentle densification. It is possible to build an extra 134,000 homes by merely reaching terraced house density within walking distance of just 25 of London’s tube and train stations, all without touching an inch of Green Belt.

What I’ve been reading

In a characteristically great piece, the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch runs through innovative pro-housing supply policies have kept rents down and what high-cost cities like London can learn from them.

YIMBY architect Russell Curtis digs into the data and finds that gentle intensification of London’s suburbs — the kind of policies we talk about above — could deliver almost a million new homes.

Over at the Yes in Our Backyards Substack, Eleanor West explains how demolishing some low-density ‘character’ homes can be the green option.

Houston has been a complete disaster of urban sprawl due to a decades long policy of no zoning controls whatsoever, so though they may have some great new policies, you did "clickbait" me into the piece by saying London could learn from Houston.

One interesting area where London can learn closer to home is Croydon. Yes, Croydon, and more particularly the southern suburbs, where (up until the new mayor was elected and cancelled it), they had a policy of allowing houses and bungalows to be bought and then developed into flats (often 6 to 9 with designs that were sympathetic to the local designs, though, tbh, most were bland 1930s urban expansion). This has added, relative to every other borough in London, a LOT of new housing and also, empirically, dampened house price inflation in the area. Oh, but it did create a lot of NIMBY response, plus some perceived corruption between developers and senior civil servants and councillors. Plus ca change etc

Hi