Why Britain should copy the Dutch

How Britain gold-plated EU red tape and made planning applications for new homes longer

London isn’t building: fewer than 4,000 new homes were started in the first half of 2025. This is a big problem for the Government’s target of building one and a half million homes by the end of the Parliament. The capital is meant to deliver nearly one third of those homes. But unless Labour can get London building fast, they will not only fail to beat their 1.5 million home target, they won’t even outbuild Michael Gove.

Why has building stopped? Dozens of rules and requirements add up to make building nearly impossible. England is dying the death of a regulatory thousand cuts.

To get London building at the rate needed to deliver 1.5 million homes by the end of the Parliament a lot then needs to change. Some of those changes will need to be big. The Chancellor’s announcement of a planning fast-track for homes on brownfield sites near railway stations could be transformative, if done right. Yet unless we are willing to shake the etch-a-sketch and create entirely new pathways to permitting homes, ending the housing shortage will require us to surgically remove dozens of (if not more) blockages.

For example, hundreds of homes were being delayed by badly drafted flood rules that required developers to produce expensive flood-modeling on the impact of big puddles. This has now been fixed. It wasn’t a huge problem, but there are probably a fair few homes that will be built now that otherwise wouldn’t because of this reform. And there will be plenty of homes built quicker as a result.

Here’s an example of another blockage: environmental impact assessments (EIAs). To get permission to build anything ‘big’ in the UK, developers are required to carefully assess the impact of that specific project on the environment. To win planning permission to build Sizewell C nuclear power station, EDF produced an environmental impact assessment 80,000 pages long. EIAs are not just for major infrastructure projects like nuclear power stations and motorways: they apply to housing developments over a certain size too.

This threshold is surprisingly low. In the UK, all developments of 150 homes or more face are screened for an EIA. The mere act of screening for an EIA is itself a hurdle. Screening reports can stretch to over 100 pages. Developers will often consult lawyers and ecologists. This takes time and money, and introduces risk. Any project considered ‘likely to have significant effects on the environment’ is then required to produce a full EIA.

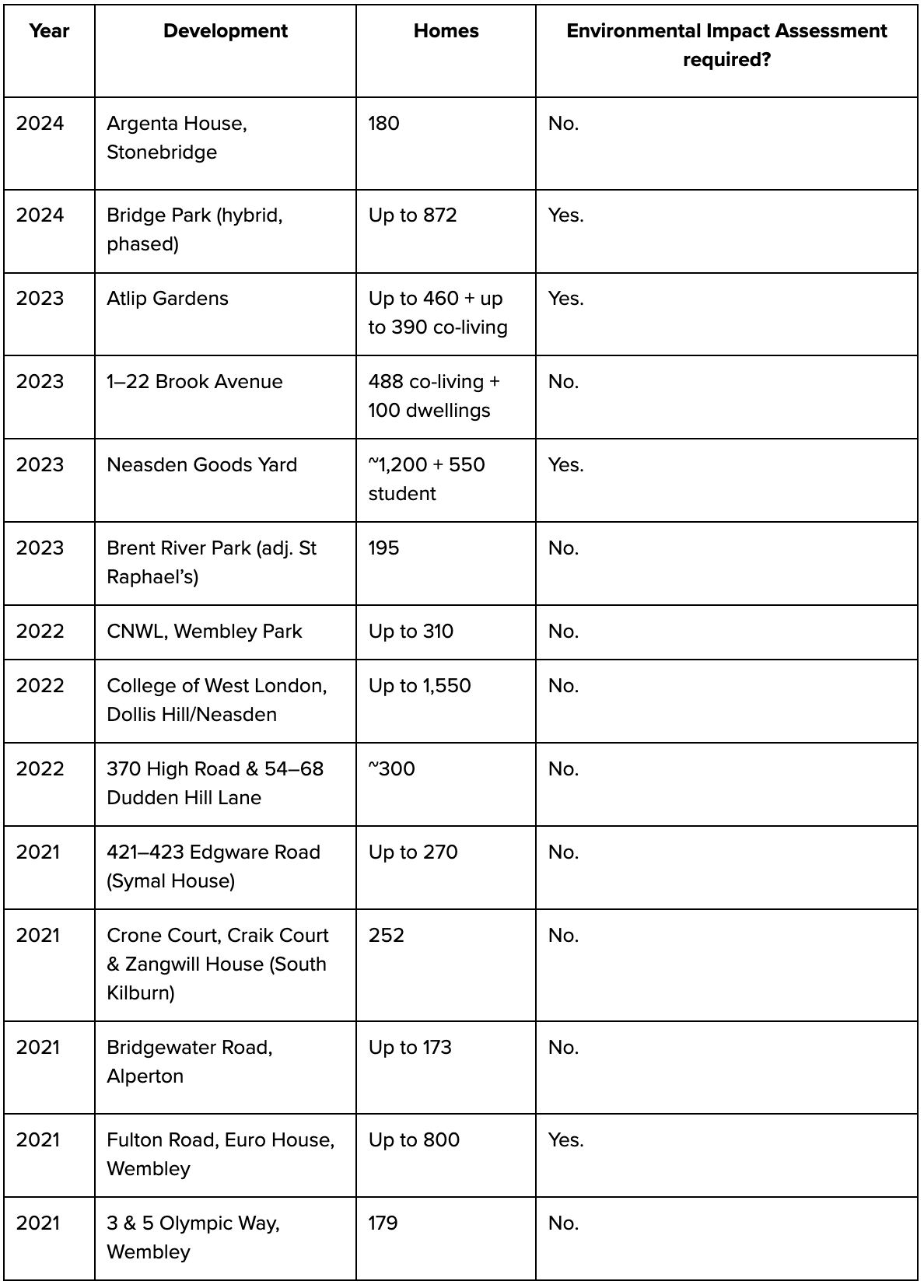

How many projects screened end up required to produce a full EIA? Let’s look at Brent, a borough where there’s been a decent amount of development in recent years. In the last five years, 14 housing projects that qualify for EIA screening have been put forward in the borough. Just around a third (4 out of 14) were then required to carry out a full environmental impact assessment.

A common argument is that planning reform is unnecessary: Britain’s problem isn’t the system itself, according to this view, but rather the poor resourcing of the system. Britain could build more homes, they say, if councils could only afford to hire more planners. There is some truth to this view. Between 2010 and 2020, per-person spending on planning fell by more than half. A lack of planners does create delay, yet the real issue is the massive expansion of the workload planners have to deal with. A developer produced a 136-page ‘scoping report’ for one brownfield development. Just figuring out what should (and shouldn’t) go into an EIA will have been a substantial task for at least one planning officer. In Brent’s case, the council outsourced the task to a specialist consultancy. Planners will spend even more time reviewing the full Environmental Statement. And every hour they spend on reviewing environmental paperwork is time they could have spent approving new homes.

That 136-page scoping report was for Bridge Park, a proposal to replace a derelict office block and a leisure centre built in the 1980s, which couldn’t be operated safely without a major cash injection, with 874 new homes, affordable workspace, and a new community centre.

Rachel Reeves wants to see an ‘automatic yes’ for new homes on brownfield land near railway stations. Bridge Park (pictured above) fits the bill. Seven minutes walk from Stonebridge Park tube station and close to the North Circular, it is harder to think of a better place to build. But to get through planning its developer will need to produce a lengthy Environmental Statement covering everything from wind to bats.

Opposite Alperton tube station on the Piccadilly Line, this project, Altip Gardens, would replace a car park, some shops, and a banqueting hall. On the evening it was approved by Brent Council, one local resident actually spoke in favour – a rare occurrence at these events – commenting on the rundown nature of the site. Still, Altip Gardens was required to carry out a full environmental statement. New developments are required to deliver a ‘biodiversity net gain’ of 10%. This project delivers a 780% net gain.

Do we really need an expensive survey to realise that this…

…is greener than this?

Britain should ‘go Dutch’

The requirement to produce environmental impact assessments (EIA) for major developments comes from an EU directive. However, there is no specific definition in the directive over how many homes count as ‘major’. When Britain was part of the EU, Brussels was often blamed for overregulation. In many cases, however, problems emerged from our government’s decision to ‘goldplate’.

This is true of the EIA regulations. While we require a screening for any development of 150 homes or more, other EU nations take a substantially less burdensome approach.

Let’s take the Netherlands for example. Not a single of Brent’s ‘major’ developments would have been screened for an EIA under Dutch rules. While we draw the line at 150 homes, they set a much higher bar: 2,000 homes or 100 hectares. Some London developments would still be screened under Dutch rules – Hackney’s 5,500 home Woodberry Down Estate regeneration for example – but most wouldn’t.

In the case of Brent, the new homes in these big schemes were overwhelmingly on brownfield land in one of the best connected parts of Britain. If homes have to be built somewhere – and they do — then there’s scarcely a better place to build than on brownfield land in one of the best connected parts of the country.

Yet at the moment redeveloping 1960s office blocks and derelict industrial land in the capital is made unnecessarily difficult by badly designed regulations. The Dutch take a more proportionate approach – for brownfield sites, we should copy them.

Thanks to Britain Remade supporter Gareth Rowswell for his hard-work over the summer investigating how EIA regulations differ across Europe and looking into their impact in London.

In Namibia, where I started my career as an environmental economist, there was a Strategic EIA approach. In other words the government would do one on an area in advance - and then produce a list of conditions for anybody operating in that area. It achieves the same outcome except with massively more certainty.

e.g. You could say - 'you can built on a brownfield site without any further environmental assessment as long as you make a £10,000 per hectare contribution to this biodiversity fund'

An important element of the Dutch system is masterplanning. Municipalities have been compelled to allocate sufficient land for housing demand since the early 20th century (UK local authorities only acquired this obligation in the late 2010s IIRC).

The masterplans are usually much better worked out than their UK local plan equivalent and create a clear mandate for the form and density of housing (compared with 'numbers superimposed vaguely on a map' style UK local planning). The planning question of 'can you build a tower block there' is much less contested because if it's in the masterplan, the question is already settled.

I've long thought that a local plan in the UK ought to be more detailed, and have the status of something like outline planning. Historically the UK housing people like — London suburbs for example — was buildable without significant development control but quite tightly specified in terms of form and look. There's got to be a way to square the circle of more housing / not all of it Deano boxes.