Why China Dominates Green Supply Chains

They are not geniuses, evil or otherwise.

This is the fourth post in a series from Britain Remade’s Policy Researcher Michael Hill looking at China’s role in decarbonising Britain. You can read the first post here, the second one on if green goods made in China are really green here, and the third one looking at just how dominant China is in green supply chains here. This post looks at why.

It’s tempting, especially in the West, to attribute China’s dominance in global green supply chains to some combination of underhanded tactics and masterful industrial strategy. The reality is less elaborate but more instructive. China does have a strategy, but it’s not unique. What’s unique is the combination of three big structural factors:

China is an East Asian country that has opted into a typical East Asian industrial model

China is a massive middle-income country, with vast income inequality, meaning there are workers at every skill and income level

China’s growth is recent, rapid and coincided with the growth of green industries

These factors compound each other, producing a country that was always likely to dominate the industries of the energy transition. The lessons for the UK across most of the green supply chain are therefore limited. However, the big exception is nuclear, where the East Asian model could and should be followed in Britain.

1. China Is East Asian

To many Western observers, China’s industrial planning looks like a unique technocratic marvel. But anyone familiar with Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan will see something much more familiar.

All of these countries followed the same basic script:

Identify a priority industry.

Support firms entering it with cheap credit and state resources. A firm’s first step is often licensing production of foreign designs or co-producing with a major foreign firm.

Let them compete ruthlessly for domestic and export markets. Opting for a single national champion is why many other countries’ industrial strategies have failed.

Scale back support over time, allowing inefficient players to die. This step ensures that inefficient companies don’t shelter behind tariff barriers, growing fat on subsidies. This is another step where other countries’ industrial strategies (like the UK’s) have fallen down.

End up with globally competitive giants.

Move on to another priority, in a more advanced industry.

This is an old story. After his successful 1961 coup, South Korea’s military dictator Park Chung-Hee set out how he would use these ideas in his book Our Nation’s Path. These ideas were being implemented already in Taiwan. Park first learned about them during his time studying the Japanese model while serving in their colonial military in the 1940s.

Comparing British and Korean industrial strategy in the automotive sector is highly revealing. In the 1960s and 1970s both governments intervened heavily to support their car companies, but with very different outcomes. South Korea, still a developing country, extended loans and subsidies to a wide range of firms, but imposed strict discipline through sales and export performance. Companies that failed to achieve scale or competitiveness, such as Shinjin, Saehan, and Asia Motors, were allowed to collapse or be absorbed, while Hyundai proved successful and emerged as the country’s global champion. Crucially, Korean firms operated behind strong domestic protection while being pushed to compete internationally, so state support came with both security and hard performance conditions.

Britain took almost the opposite path. By the 1960s, one major player, the British Motor Corporation (BMC), was failing, while Leyland Motors remained relatively healthy. Instead of allowing BMC to go under, the government encouraged a merger between the two, creating British Leyland in 1968. The new company was plagued by poor practices, constant strikes, and chronically weak profitability. It was sustained by political protection: ministers pressured banks to provide easy credit, and when losses mounted after the oil crisis, the government stepped in with nationalisation in 1975. Over the following decade British Leyland absorbed hundreds of millions of pounds in taxpayer funds, but without meaningful reform or export discipline. By 1982 it was being dismantled and sold off in pieces, with the last part leaving state ownership in 1988.

The contrast is stark: Korea’s industrial strategy was tough, selective, and oriented toward competitiveness, while Britain’s was defensive, preserving failing structures until they collapsed under their own weight.

China, since leaders consciously chose this path in the 1970s, has followed this East Asian script for industrial strategy almost exactly: moving from textiles and basic manufacturing into steel, shipbuilding, electronics, and now EVs, solar, and batteries. The main difference between China and other East Asian countries is scale.

Japan wouldn’t even be China’s most populous province. South Korea wouldn’t break the top 10. The East Asian industrial strategy hasn’t changed; China has simply applied it to a population of 1.4 billion.

There are no big Japanese social media or mobile phone companies. Taiwan does not make many cars. Korea is absent from global aviation supply chains. China is too big to leave whole industries on the table. While industrial and tech success undoubtedly serve China’s foreign policy goals, a country with 20% of humanity needs to be good at many things to deliver decent living standards for all those people.

China’s direct support for specific industries and companies is real. A US State Department funded report found that China spent at least 1.73% of their GDP by changing public investment, subsidies, regulations, and planning to support key companies in 2019. This was double the share of the next highest country analysed, South Korea. This kind of strategy is a standard part of the East Asian development model, an effort to move up the global value chain.

This strategy also explains why China has overcapacity. Often this is presented as a nefarious plot to dump cheap goods on the west, make Western firms go bust and then jack up the prices. In fact, overproducing goods is a major downside of this strategy that China seeks to minimise.

The overcapacity comes from firms that China has subsidised, that are not going to make it on their own. Chinese taxpayers are left holding the bag. State support for green industries in China is almost entirely gone. Companies that were propped up by subsidies and cheap credit are going bust and taking their overcapacity with them.

2. China Has Workers for Every Job

One of the most overlooked aspects of China’s dominance in green industries is its economic structure. China is a middle-income country with enormous income inequality. This gives it a workforce that spans the full spectrum of skill and cost, from highly skilled, globally competitive engineers to ultra-cheap labour.

At the top: 150 million people with tertiary education; 12 million more graduating each year. Major cities like Beijing and Shanghai have living standards as high as the UK or higher. Chinese firms lead in battery chemistries, solar cell designs, and AI-driven energy systems.

At the bottom: Around 140 million people live at Senegalese income levels. Some provinces have literacy and nutrition outcomes comparable to North Africa or Central America. Nearly a billion people live at standards below the UK’s poorest decile, with many far lower.

In this context, it’s no surprise that China can provide both the R&D talent to design the future and the cheap labour to build it. The UK, like most rich countries, can do some of the first, but none of the second. Vietnam or Indonesia can do the second, but not the first. China can do both. As wages rise in coastal regions, much of China’s low-end production has simply migrated inland. Rich China has “outsourced” to poor China.

China’s graduates have helped take many of their companies to the frontier of highly competitive net zero related industries. Goldwind turbines, LONGi Panels and BYD cars are all at least as good as and arguably better than their western competitors on quality grounds.

In some sectors the advantages of readily available highly skilled and cheap labour compound. For example, Chinese wages for semi-skilled manufacturing jobs on the factory floor are much lower than in the west. And the innovativeness of China’s engineers means they need far fewer of these workers. Hannah Ritchie has found that in battery factories the US uses six times as many workers per GWh of production compared to China. With lower wages and fewer workers needed it is very difficult for anyone in the West to compete. Companies like Volkswagen once moved to China and set up joint ventures chasing big new markets. They now want to stay in the country because many of the most innovative companies in EV manufacturing are there. To stay at the technological frontier, they need a base in China.

This also explains why the human rights abuses in Xinjiang, while abhorrent, are not key to China’s success. Creating forced labour camps is not necessary to create pools of cheap labour in China. Even after decades of advance, China still has hundreds of millions of people who will freely work for low wages. The purpose of the forced labour camps that were widespread from 2017-19 and the myriad other forced labour practices still in force are to suppress Uyghurs and Islam. This is cultural and ethnic policy driven by racism, anti-religious hatred and a pathological fear of separatism, not industrial policy.

3. China Grew Fast and Late

Timing matters. Other East Asian economies began growing much earlier. By the time the Kyoto Protocol entered into force in 2005, Taiwan and Korea were both rich countries, while Japan had been a rich country for decades. None of them were sources of cheap labour any more. Thanks to Mao, China didn’t get going until the 1980s, and didn’t enter middle-income territory until the 2000s. There were huge pools of cheap labour to deploy at just the time a new industry was growing that needed cheap labour. China was growing just as the Net Zero economy was taking off. Would it be possible for China to double its GDP since 2013 without becoming a major player in the industries that emerged during that time?

Wise industrial policy is not the major factor in China’s dominance of goods crucial to the green transition. It’s the natural result of a very big country, with a newly rich consumer base, growing rapidly into the fastest-growing sectors in the global economy.

Should we copy China?

It is often argued that China’s rise is the result of “cheating” through subsidies. It is true that Beijing poured support into green industries, but this is neither the whole story nor a replicable one. Those subsidies worked because of the broader context in which they were applied: vast pools of low-wage labour, concentrated industrial hubs, and a national priority to lift hundreds of millions out of extreme poverty.

A walk through the rare earth mines of Bayan Obo or the ball bearing factory clusters of Wafangdian shows why this cannot be transplanted. These places have built huge, specialised ecosystems around low pay, labour-intensive industries. They are environments few in the West would be willing to live in, and workers earn wages few in the west would be willing to live on. For a much poorer China of the 2000s, subsidising mid-market sectors like solar panels made sense: it created jobs, built industrial capabilities, and raised incomes.

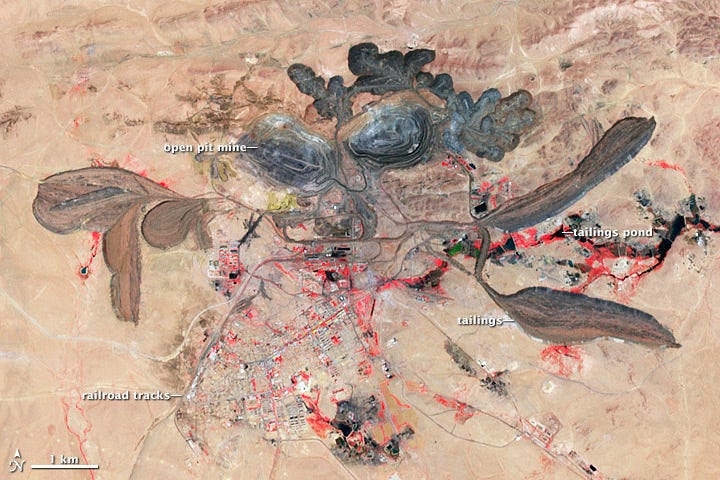

Bayan Obo Mine from: Bayan Obo Rare Earth Mine, Inner Mongolia, China

But that same approach would not work elsewhere, nor even in China today. Manufacturing solar panels in a rich country at today’s prices would either leave workers worse off or require heavy ongoing subsidies, diverting resources from more productive uses. And in China itself, the model has already run its course. New renewables projects stopped being eligible for subsidy in 2021. Market driven pricing will dominate by the end of this year and be expected to bear the extra grid costs it generates. EV purchase subsidies ended in 2022 and tax breaks for EVs will be halved in 2026 and end in 2027. State support for green industries has been withdrawn, critical minerals mining is being shifted abroad, and leaders now speak instead of “high-quality growth” and a “beautiful China.” The policy frontier has shifted to semiconductors and other advanced technologies.

The lessons the UK could learn from China: do not have sky high energy costs, do not subsidise failing companies for decades are ones we could just as easily learn from other countries of a more similar size and level of development to the UK.

The nuclear exception

Where the East Asian model may be more relevant is in nuclear. In Small Modular Reactors, Britain has a world leading company in Rolls-Royce SMR and we need to back them. States following the East Asian model provided protection and orders for companies that would drag them up the global value chain, without eliminating competition. In China, Korea or Japan a domestic company like Rolls-Royce SMR would already have several orders on the books, while leaving the field open for competitors. In Britain we forced Rolls-Royce through a 2 year process (that cost £22 million to the taxpayer that mostly went in fees to consultants and unknown millions to Rolls-Royce themselves) to become the ‘preferred bidder’ for working with Great British Nuclear. They were forced to provide hundreds of pages of explanations of how they will provide ‘social value’. Questions included how they would employ people seeking asylum, which is illegal and punishable with 5 years in prison. Where East Asian states support their most innovative companies, the British state drowns them in pointless paperwork that costs millions to fill in. At least Rolls-Royce SMR does have a route to market with the plan for 3 SMRs at Wylfa.

In gigawatt scale reactors Britain is anything but a world leader: we build foreign technology at prices higher than anywhere else in the world. After decades of not building any nuclear and before that taking a wrong turn into gas cooled reactor designs (almost everywhere else in the world uses light-water based designs) we have not been at the cutting edge of this technology for decades. Again there may be lessons from East Asia. We need to learn from foreign best practice. Our best option would be to create a regulatory regime where foreign companies from countries we trust (Korea, Japan, France and the United States) could more easily build gigawatt scale nuclear, following the recommendations of the nuclear regulatory taskforce. This would enable us to develop a supply chain at home that could provide the foundation for a British company or for the state to set up our own nuclear company. Without starting out making the Ford Cortina under license, or hiring engineers from British Leyland to build the Pony, it is unlikely Hyundai would have become one of the world’s largest car manufacturers. If Britain wants to build its own gigawatt scale nuclear plants and maybe even one day export them, we need to face the reality that we are a long way behind the cutting edge and learn from the East Asian model.

Subsidies and support are clearly part of the story of how China succeeded. But China did not outwit the world, it out-scaled it. A huge country, growing quickly at the right moment, with workers for every job and energy to power them always had a very good chance of leading the industries of the transition. China’s industrial policy made sense for them at the time, but outside of nuclear, there are few lessons for the UK. China’s cheap energy underwrites the whole economy and that is where the most useful lessons are. The story is less about genius or cheating, and more about what happens when size, timing, and structure align.

Useful analysis. There is a piece missing : China identifying a strategic interest in becoming an electro-state to reduce its dependence on imported hydrocarbons. There is a helpful alignment between moving to renewables + batteries + nuclear to run the domestic economy ( and so reduced exposure to the risk of foreign powers cutting off oil and gas supplies) and achieving unrivalled scale economies in sectors that are seeing rising global demand. Delivers progress towards target outcomes for security, economy and climate change mitigation.

I enjoyed this article so much that it ended too soon! I was expecting you to get into why the APR1400 specifically would be a good reactor design to favour, or what British biotech regulation should copy from China.