Will Labour’s New Towns succeed?

12 “New Towns” have been picked: are they the right ones?

When Labour announced their New Towns policy in opposition, the response from Britain’s YIMBYs was mixed. There’s a lot to be said for building entirely new settlements. For one thing, they seem to get around the NIMBY problem. Local objections can’t sink a project if there are no locals to object. Likewise, due to accidents of history, Britain is blessed with woefully under-utilised railway stations. My favourite example is Pilning in the South West. Just 10 miles to the north of Bristol: only two trains a week stop there. They recently removed the footbridge so only Eastbound trains can stop there now.

Yet, Britain’s experience with ‘New Towns’ is mixed. For every Stevenage, there’s a Skelmersdale. Too often, New Towns were planned without proper respect for the economic reality that it is easier to move people to where the jobs are than it is to move jobs to where people were. Many are frankly ugly, too.

More recent attempts to build New Towns have been beset by problems. It is inaccurate to say that attempts to build a New Town in Ebbsfleet failed due to the discovery of rare spiders where they wanted to build. In fact, they have failed because of the discovery of rare spiders on a plot of land quite far away from where they want to build.

New Towns are complicated – and will take time. Without radical reform, they will take far more time to build than their post-war equivalents. Blame rafts of planning and environmental legislation for that. New Towns are unlikely to make a dent in the Government’s 1.5 million home target.

Still, done well, New Towns could be a powerful tool in the fight against housing scarcity. When the Government announced the creation of a New Town Taskforce, Britain Remade and Create Streets teamed up to explain how to build them quickly and well in the right places.

How to build new towns well (and fast)

If the history of New Towns tells us anything, there are three things that determine whether a new town is a success or a failure: location, location, location!

What’s a good location? We came up with seven principles, but they can effectively be condensed into three.

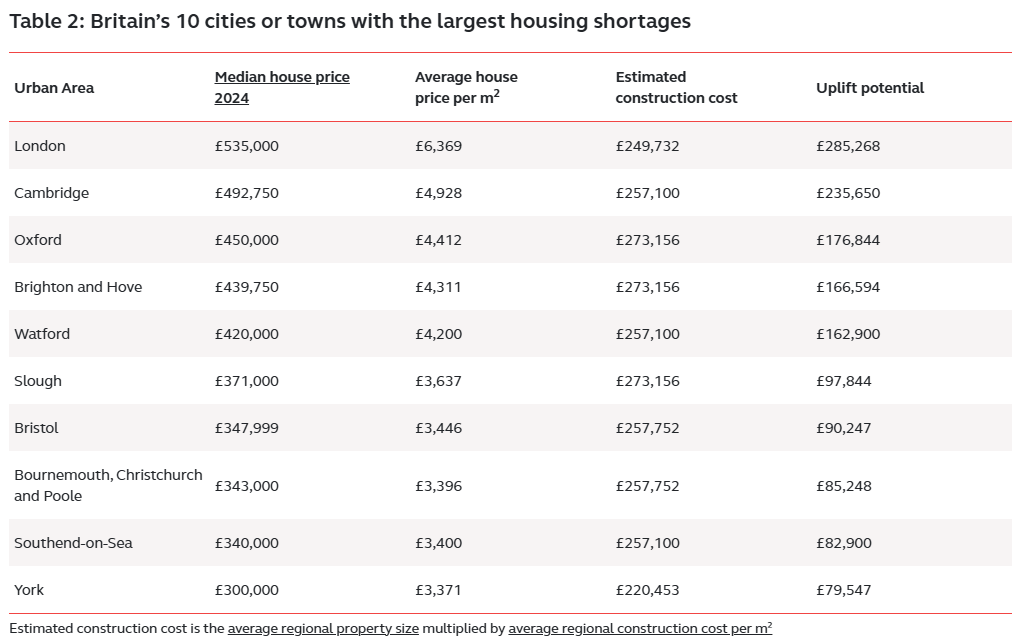

The most important is demand. Britain’s national housing crisis is best understood as a collection of local shortages – primarily (but not exclusively) concentrated in London and the South East. This isn’t to say housing affordability isn’t an issue elsewhere, but the places where building new homes delivers the most bang per buck are close to the capital.

This is, in part, because London exports its housing crisis. People who can’t afford to live in the capital move out to commuter towns – in my case, a ‘commuter city’ in Brighton – this bids up rents there and in turn forces others out to places like Worthing (sorry!) and so on and so forth.

If possible, New Towns should plug it into existing cities even if the aim is for the new town to be a centre of employment eventually. This might mean urban extensions but it could also mean commutable distance to a larger anchor. This is crucial for drawing workers to an area. If a New Town is built without this, attracting workers (and in turn businesses to employ those workers) will be a tough sell.

The second key factor is infrastructure. In a triumph of post-war planning, Skelmersdale New Town opened just as Skelmersdale’s railway station was closed and demolished. We should not repeat this mistake. New Towns should be built to take advantage of under-utilised infrastructure.

HS2, for example, will unlock lots of capacity on the West Coast Mainline allowing more commuter trains to be run from old New Towns like Milton Keynes.

One opportunity is to create Mirror Towns. Historical development patterns mean that many railway stations have a town on one side and fields on the other. The idea behind Mirror Towns is to build on the other side to, in effect, mirror the town and create a new city centre.

When a new development is built, in the right places – where housing is scarce – it can generate a cash uplift. Part of this needs to fund local infrastructure, but in some cases the uplift can be so great that it can contribute to bigger infrastructure projects. For example, a New Town in Salfords (near Gatwick Airport) could help fund an upgrade to fix a notorious rail bottleneck at East Croydon.

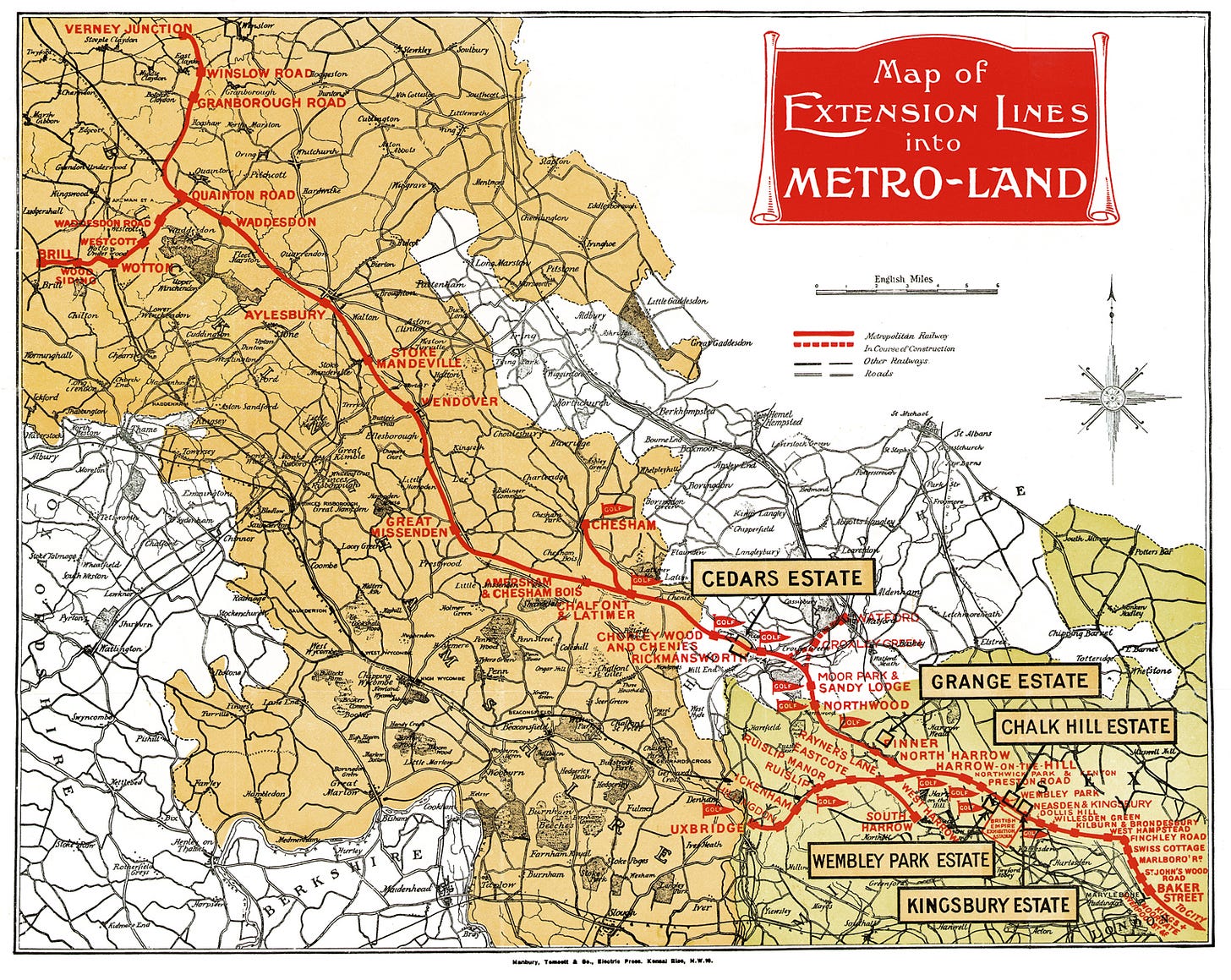

This isn’t a new idea. Japan finances new railways through a mix of development on the line whether that’s shopping malls above stations, theme parks along the route, or homes nearby. Britain did it too. Metroland – the suburbs and villages along the Metropolitan line – were built by the Metropolitan Railway Company as a way of making their tube line viable.

The third key factor is room to grow. The hope is that new New Towns will be successful. If they can’t grow further either through densification or expanding outwards, then they will end up facing the problems the town itself was built to solve.

Most of our suggestions were for New Towns within the South East taking advantage of spare capacity on the West Coast mainline, commuter lines, and the recently-built Elizabeth Line. We also backed calls – first made by UKDayOne (now Centre for British Progress) for a New Town in Tempsford – the site of a new interchange between the East Coast Mainline and the new East-West Rail (a line between Oxford and Cambridge).

That’s the where. What about the how?

Within 11 months of the New Towns Act receiving Royal Assent, Stevenage was officially designated as a New Town. A month later the Stevenage Development Corporation was established and within five years the first families moved in.

There was some public engagement, but nothing like a formal statutory consultation as we know it today. At one public meeting, Housing Minister Lewis Silkin was chased out to cries of ‘dictator’. The air was let out of his tires by disgruntled locals. None of this was able to delay building.

Ebbsfleet by contrast – our newest New Town – has proceeded slowly over two decades. And the plans have been dramatically curtailed in the process.

It is crucial that the Government uses its political mandate to avoid the plans getting bogged down and delayed to the next election. In some cases, that should involve using Acts of Parliament where necessary. Development Corporations (the vehicle typically used to deliver New Towns) should be given new transport powers, while Ebbsfleet-style jumping spider blockages should be avoided by moving to a strategic approach for environmental protection.

And to make the towns attractive and desirable, building should proceed to a design code using a pattern book of popular architectural styles crafted with public input using visual preference surveys.

What kind of places do we want to build?

It’s essential that New Towns become just that towns, and not merely large suburbs where car-dependency is unavoidable. Northstowe, a new ‘town’, built near Cambridge is a good example of what not to do. It’s a collection of mostly detached houses without a shop, gym, or GP. The aim should be to build at gentle densities so people can walk to pubs, shops, and transport.

Politicians often talk about building greener buildings. There is a lot of interest at the moment in the concept of zero bill homes, with solar panels on roofs, heat pumps built-in as standard, top quality insulation, and battery storage. Yet, as important as it is to build ‘green buildings’, we should also look to build ‘green places’. Where people do not want to pull down and rebuild buildings decades later and where people can get to work or social occasions without getting in the car.

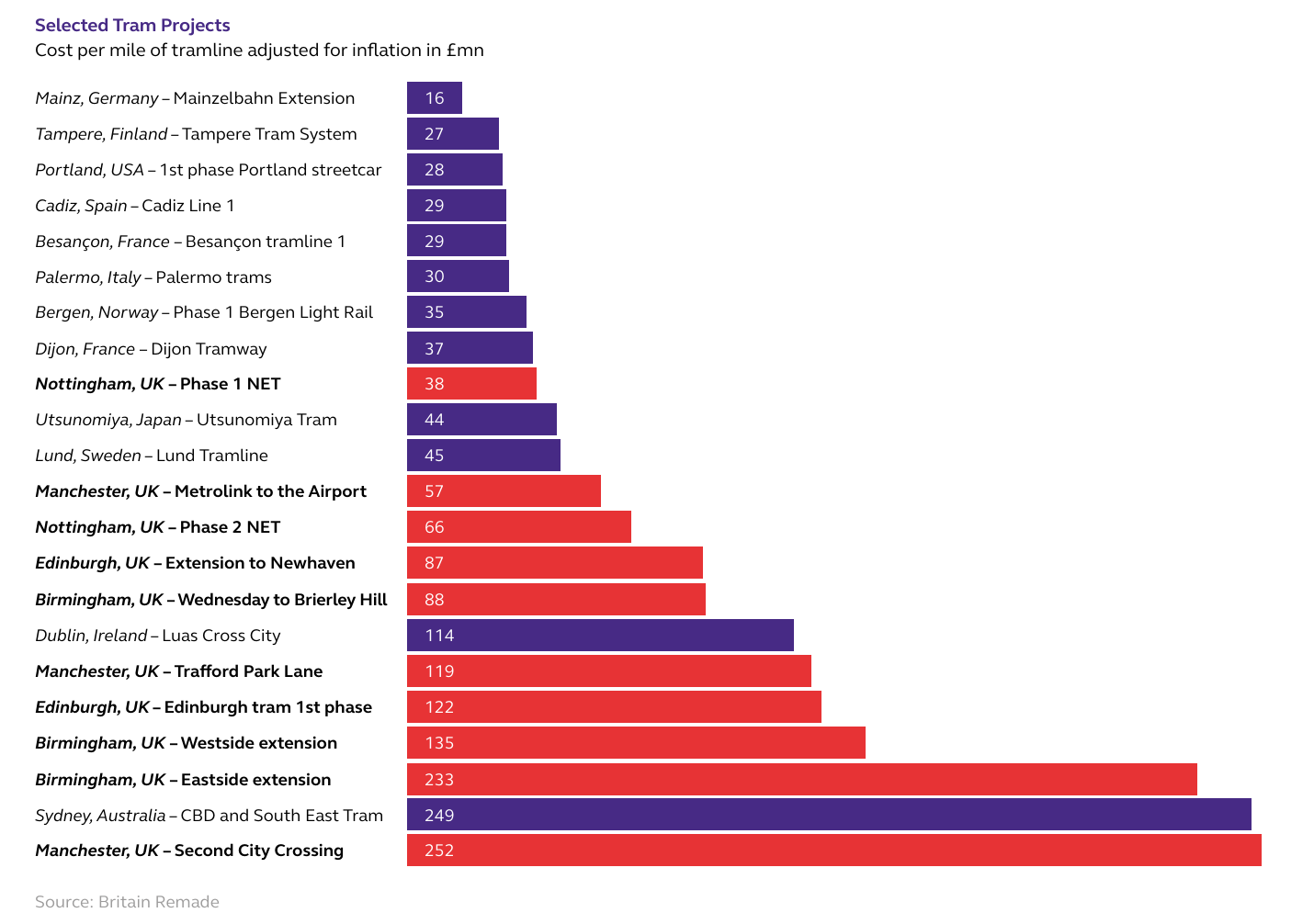

For bigger New Towns like a Cambridge New Town – a massive urban extension to a fast-growing but housing-constrained city – trams would be appropriate. Some argue trams are too expensive to build. Looking at recent tram projects in this country, they might have a point. Yet just across the Channel they build them for much, much less. Less than half as much in some cases. If we copy them and do what works – here’s an idea: let’s not move every single pipe or cable underneath a new tramline – then we can get costs much lower.

Did the Taskforce listen? And has the Government listened to them?

Kind of. Let’s start with the big ‘wins’: one big problem we identified with the way Development Corporations work at the moment is that they have powers over planning homes and offices, but not planning transport. The result is that things built by Development Corporations are often reliant on approval from other public bodies to do anything. This hasn’t tended to be a huge problem in the past because Britain has tended to say: here’s a bit of brilliant infrastructure, let’s build some (let’s face it, too few) homes near it. Old Oak Common Development Corporation doesn’t need transport powers because the area it controls already has a dozen tube stations. (It does however need the permission to build on the Park Royal industrial estate.)

Yet, if you want to build a brand new town with a tram or with a rapid-bus route, then the Development Corporation needs to get local leaders/authorities on side. Not only will this slow things down, it might also limit the New Towns ambitions. In some cases, local authorities might use this power to extract new infrastructure for themselves, threatening the viability of the New Town.

And then there’s Trams. One of the New Towns suggested by the Taskforce was Milton Keynes. This might sound strange given Milton Keynes itself is (or was?) a New Town. Yet the Taskforce’s suggestion is Milton Keynes could be dramatically densified unlocking a town’s worth of homes. One way to expand the population of MK without clogging up its famous roundabouts is to build a tram, but at current costs that won’t be easy.

So it’s extremely heartening that the New Towns Taskforce cited Britain Remade and Create Streets research showing how tram costs could be cut by reforming planning approvals, moving fewer utilities and creating a degree of national standardisation. In classic government Taskforce fashion, they’ve called for a new taskforce to explore whether our suggestions actually would cut costs. Not perfect (we’d just get on with reforming it), but certainly positive.

Density is another big positive. The Taskforce recommends New Towns are built to ambitious densities with planners setting minimum density standards. Welcome too is the fact they recognise it can be delivered not just through high rise towers, but mid-rise apartment buildings, terraced housing, and mansion blocks.

It’s not all perfect however. There’s a lot of everythingism. It is not enough just to alleviate the housing crisis by building near cities with overheating housing markets. They also need to build substantial levels of social and affordable housing: a minimum target of 40% in fact. There are extensive demands for consultation, which will delay delivery. And while there’s references to design codes, there’s almost nothing on building in popular architecture styles. This is a shame considering that the Government launched the New Towns policy by talking about places like Nansleden and Poundbury – where homes are built in styles that normal people (i.e. non-architects) like. When the public are surveyed with simple visual preference surveys (i.e. do you prefer this building to that building?), it reveals a clear disconnect between planners, architects, and the general public.

And what about the Towns themselves?

When it comes to the most important bit – where the towns will actually be built. The Taskforce have done a decent, if not flawless, job.

There’s some weird quirks. First, four of the twelve New Towns aren’t actually ‘New’, but rather large urban developments in cities and towns already exist. In the case of Leeds and Manchester, they’ve given them names like ‘Leeds South Bank’ and ‘Manchester Victoria North’, but there’s also just ‘Milton Keynes’ and ‘Plymouth’.

Naming aside, there’s a strong case for urban extensions like this. First, there’s no first mover problem. You aren’t convincing people to upsticks and move to a whole new town that might take years to feel like a proper place. Second, urban extensions require less infrastructure as new residents can piggyback on the city’s existing infrastructure.

When it comes to the actual ‘New’ and actually ‘Towns’ New Towns, the list is strong – though some suggestions have more problems than others.

The most exciting suggestion was the most heavily trailed: Tempsford. Sitting at the intersection of the East-Coast Mainline and the soon-to-be-completed East-West Rail, workers living in this New Town would be able to access jobs in London, Cambridge, Oxford and Milton Keynes. Unless Tempsford is built out, only a tiny village will have access to one of the best connected railway stations in Britain. It is as close as it gets to a no-brainer. If you wanted to build a brand new town, there is simply no better location.

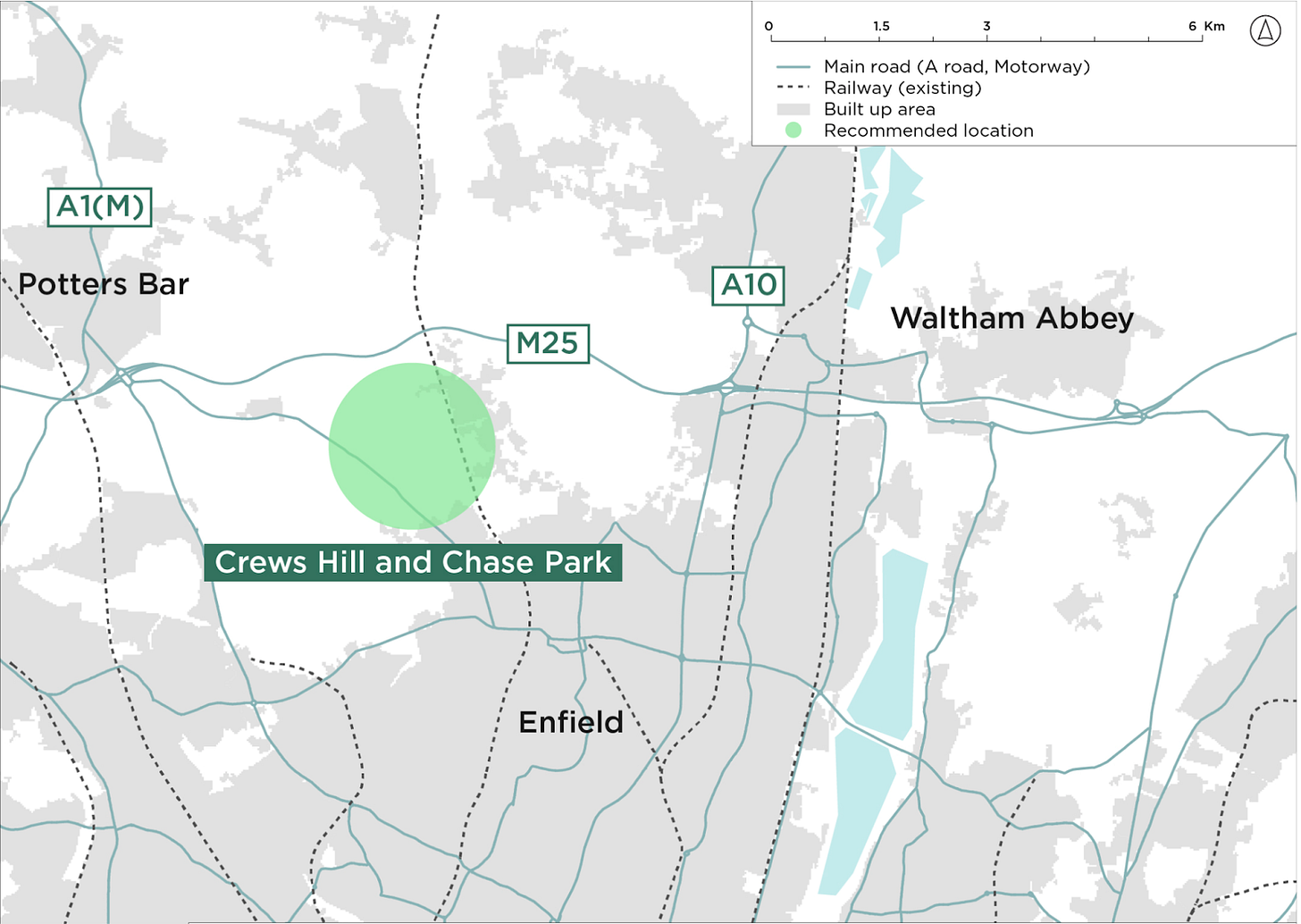

The other big one is Crews Hill in Enfield, London. Enfield is one of London’s biggest boroughs and also one of its least dense. Crews Hill is the least used station in the borough. In fact, it is in the top ten least used stations in London. The reason nobody uses it is simple: almost no one lives there currently. The station is surrounded by Green Belt land, which means that nothing can be built currently. However, the point of the Green Belt isn’t, as some pretend, to protect greenfield land. Rather, it is to prevent urban sprawl and car-dependency. A New Town built around Crews Hill railway station would be anything but car-dependent. That’s why Crews Hill made Britain Remade and Create Streets’s longlist.

The key challenge is upping the frequency for trains into Moorgate. At the moment, Crews Hill gets four (rather crowded) trains an hour into Moorgate at peak. One way of doing this would be to take the Great Northern Line under TfL control, allowing for much more frequent (but slightly slower) services.

The Government’s response to the Taskforce suggested the above two actually-new New Towns would be taken forward. However, the Taskforce recommended more.

London has another New Town proposal in Thamesmead in Greenwich. Sitting on the Thames (as the name suggests), Thamesmead is home to lots of brownfield land (and a few prisons including Belmarsh). If the site was built to its full potential, it could unlock a lot of homes - 15,000 according to the Taskforce, but even more if ambition on density was lifted. The other big advantage is the site is owned almost entirely by a single-landowner making it much easier to plan and assemble the land quickly.

There’s one problem. Thamesmead is extremely poorly connected. The only way a resident would be able to get into London to work would be via a bus-ride to Woolwich station on the Elizabeth line. This could change if an extension to DLR (estimated cost: £1.5bn) was funded.

There was a proposal to build 15,000 homes in Oxfordshire where an old US airbase was hosted. One big issue with the idea is that while the land is close to Oxford by car (15 minutes), it would take twice as long by train and the site itself is an hours walk away from the station. And trains are currently infrequent – stopping just once an hour.

Brabazon near Bristol was another suggestion. Bristol has the worst housing crisis outside of the South East. In the most expensive bits, floorspace goes for £5,900 per square metre. With a train line set to reopen to commuters soon, Brabazon to the North of Bristol could make a big dent in Bristol’s housing shortage. At the moment, 6,500 homes are planned for the site, but the New Towns Taskforce reckons as many as 40,000 can be unlocked with New Town status.

Many of the proposals piggyback off existing developments and expand them. Marlcombe near Exeter is a good example. Already 8,000 homes are proposed for the site, the taskforce reckon development could come faster, at a bigger scale, and in a better-planned way if the area was given New Town designation.

There’s also a proposal to build a New Town in Adlington, Cheshire where floorspace values are high. While it’s connected to Manchester, Stockport and some large employers in life sciences, there’s a caveat. High house prices nearby may be less driven by job demand (Manchester is near but connectivity could be a lot better) and more by amenity value. Letting more people own homes in an attractive and green part of the country is a good thing, but we should probably pare back our expectations of boosting growth through agglomeration. More than others, it is important that new homes here are attractive.

Our Verdict

New Towns were one of Labour’s few genuinely eye-catching policies at the last election. Yet, they entered office without a clear idea of what or where they wanted to build. They lost a year as a result – and the odds of people moving into any of their New Towns before the next election are slim.

They gave the job – that they should have done in opposition – to a team of the best and brightest.

If you were banking on New Towns to solve the housing crisis, then the taskforce’s report will almost certainly disappoint you.

But all in all, the Taskforce have done a pretty decent job. The three suggestions of proper New Towns the Government is set to run with are all in good locations. They have not suggested a new Skelmersdale or Runcorn by any stretch of the imagination.

The placemaking principles should have said more about beauty, but the ambition on density is welcome. Most exciting of all is the push on trams. The Taskforce’s endorsement of reforms to make them cheaper to build could be the spur needed to bring in the reforms needed to get costs down.

It’s positive to see both Victoria North and Leeds South Bank on there because we need to prove we can accelerate brownfield development at scale in neighbourhoods that are adjacent to the commercial core of industrial cities. There’s whiff of ‘cheat’ as both sites are in growing cities with competent local authorities who have a well thought out strategy and development partners in place. The big win is creating a pattern that could be used in Liverpool, Birmingham and Sheffield.

Good analysis Sam. I think Adlington is the black sheep of the whole thing. It appears to have only been chosen (above building new towns in other places near Manchester) due to the rail station and consolidated ownership. This is a problem for two reasons, in addition to the one you mentioned.

The first (rail station) lends itself to a mirror town. However, the “mirroring” is largely prevented by a natural burial ground and the historic parkland of Adlington Hall (and some good old flood plain).

The second (consolidated ownership) should not really be a consideration for now towns, as I understand it, due to the development corporation model! Seems quite silly.

The issue you identify (about the house prices being due to amenity, that being of Pressburg and the rest of the footballer belt) is another obvious issue, and there is a lot of talk of no effect to the current “village” (suburban development next to a railway station). This would result in a low-density core to the new town, a crazy proposal! Coupled with the parkland, etc. on the other side of the road, and it would be a ring settlement, which is even more mad.

I think Adlington and areas around Manchester is worthy of an investigation to ensure that spunk is not spent on a blunder when really success is the only viable option.