7 thoughts on the OBR scoring planning reform

What we learnt at the Spring Statement

Has Rachel Reeves discovered the magic money tree? The OBR’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook was mostly painful reading for the Chancellor. GDP growth forecasts were slashed. The OBR now predicts GDP will grow by just 1% in 2025 - half what they thought it would be six months ago. Outside of a 1.4% boost this year, real wages are set to stagnate for the length of the Parliament. Tough choices on tax and spending were unavoidable as a result. But, there was one silver lining.

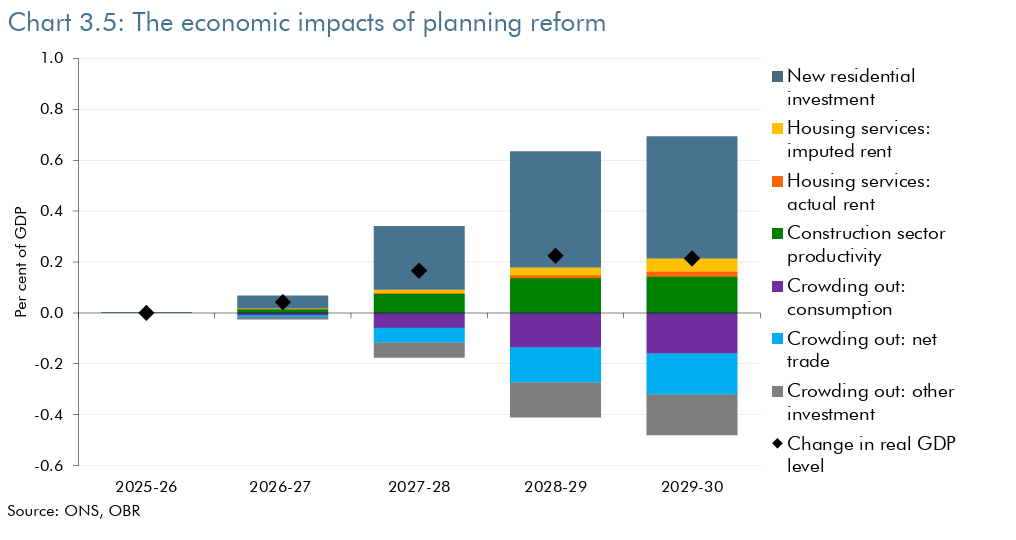

The OBR gave its seal of approval to the Government’s reforms to the planning system. Re-introducing mandatory housing targets and allowing development on the grey bits of the green belt are forecast to deliver a £7bn boost to GDP by the end of the Parliament (and a £15bn boost after 10 years).

This is, as Reeves pointed out in her speech, “the biggest positive growth impact that the OBR has ever reflected in its forecast.” And remember unlike other pro-growth measures (e.g. tax cuts), planning reform doesn’t cost a penny.

Here are 7 thoughts on what this means.

Restrictions on housebuilding mean fewer funds for hospitals, schools, and defence. One important, yet neglected, point in the housing debate is that restrictions on development not only make it harder for people to make rent, but by cutting growth rates they also reduce the amount of money available to fund public services. In fact, there will be £3.5bn more money for public services in 2029 almost entirely because of the changes to the National Planning Policy Framework made last year. Politicians are often criticised when they put forward unfunded plans to increase spending or cut taxes, the same scrutiny should be applied to unfunded NIMBYism. Opponents of the Government’s grey belt policy should be asked: what should we cut instead – defence, the NHS, or pensions?

The OBR do not think Labour have done enough to get 1.5 million homes built by the end of the Parliament. The OBR predicts that 1.3 million homes will be built over the next five years. We have just four of those years left in this Parliament - so as it stands - Labour are set to significantly undershoot their housing pledge. In fact, the OBR estimates that it will take ten years for the reforms to push UK-wide housebuilding levels to just 320,000 per year. And it is worth remembering that Labour’s 1.5 million homes target is just for England. If just 1.3 million homes were being built across Britain then that’d translate (on a population basis) to around 1.1 million homes in England. In other words, the Government are on course to miss their housing target by a city the size of Newcastle, Milton Keynes, and Plymouth combined.

It isn’t complicated: more homes means cheaper homes. The OBR forecast that the additional housing built as a result of the Government’s reforms will bring house prices down. But, admittedly, it’s not by a lot. The 0.5% increase in the housing stock will cut house prices by just under 0.9%.

To make housing affordable we need to go much further. Population and wage growth will see house prices growing by 11.3% overall. Some such as the commentator Pete Apps have argued this shows that the YIMBY argument for boosting private supply doesn’t add up. This may seem superficially persuasive, but the YIMBY argument has never been that a small increase in housing supply would make housing affordable overnight. Britain has built up a four million home backlog compared to Western Europe (and a 5.6 million home backlog compared to France, Italy, Germany and Spain) over decades of misguided post-war planning policy. To make housing cheap again, Britain needs a large and sustained increase in housebuilding.

We don’t know too much about the OBR’s model for housing supply. The OBR’s explanation of how they reached their estimate is opaque. Some points (e.g. the figures they used to model the response of house prices to new supply are detailed) but others such as how they calculated how many more homes will be built as a result of the NPPF changes are effectively a black box. We’ve asked the OBR for their workings. (For a critique of the way the OBR produces its forecasts, I recommend this very good UK DayOne report.)

Location, location, location. There are two key ways in which a boost to housing supply increases GDP in the OBR’s model.

First, there’s what they call construction sector productivity. In many parts of Britain, the cost of building a house is only a fraction of what it’s worth. The rest is down to the value of the land underneath it. Britain, by the way, is particularly extreme in this sense. When land is freed up for development, its value can shoot up. This allows the construction sector to deploy capital and labour on extremely productive tasks. Second, there’s the flow of housing services. GDP is ultimately a measure of what our economy produces and more construction means we can as a nation consume more housing each year.

In both cases, but particularly the first, location is paramount. The UK is an international outlier in just how much of the value of a given property is the land underneath it (rather than the cost of the building on top). But, national averages tell a simplified story. In some parts of Britain, bits of the North East in particular, development can only proceed with subsidy. In other parts, such as some areas in London, house prices can be up to four times build costs. Higher housing targets in the former are unlikely to boost construction sector productivity meaningfully. Higher housing targets in the latter, by contrast, will have a much larger pro-growth effect. This is why Britain Remade have argued that London’s housing target being cut from 100,000 (as the previous method called for) was a mistake.

The reforms to the NPPF are only the start. The OBR estimate that the changes to the NPPF announced post-election will get an extra 170,000 homes built over the next five years. This shouldn’t be sniffed at – every single one of those homes will be life-changing for someone. But let’s be clear, this is not and it must not be the full extent of the Government’s planning reform agenda.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill’s reforms to environmental regulations will end the absurdity of nutrient neutrality rules blocking thousands of homes across the south of England. Making it harder for political planning committees to block schemes approved by planning officers will help too. There’s also scope for a big reduction in red tape through what are known as National Development Management Policies (NDMPs). At the moment, every single council in Britain has its own development management policies covering things like flood risk. NDMPs would change that by swapping out 300 or so separate policies for just one.

But, the most powerful proposal is the Brownfield Passport – in essence, an automatic yes for housing on previously developed land. If done right, England could experience a New Zealand-style building boom.

Unrelatedly: Landlords in Auckland are now offering would-be tenants $500 grocery vouchers to win their custom. As one Kiwi housing analyst put it: it’s like musical chairs but there’s more chairs than people.

Has anyone looked at OBR forecast accuracy? If you’re looking at anything data more than a few years out, then it becomes extremely difficult to forecast within a 20-30% range imo.

Your Question “ Opponents of the Government’s grey belt policy should be asked: what should we cut instead – defence, the NHS, or pensions?” is childish. Of course there are many ways to get growth - and not via cuts. For example, remove regressive tax measure like the new tax on employment. Don’t insult your readers by posing silly questions.