Where should we build 1.5m homes?

The case for building more homes in expensive cities

At the heart of Labour’s plans to build 1.5 million homes over the next five years are housing targets. Housing Secretary Angela Rayner’s plan tweaks them in three key ways.

Housing targets will be binding. Areas must have a valid local plan to meet the target. If they don't, a beefed-up ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’ applies. Rejecting planning applications will become much harder for them. In extreme cases, non-compliant local plans will be rewritten by the Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government.

Annual housing targets will be increased nationwide from 300,000 to 370,000. This is to account for current low levels of supply, which mean that we have to build more than 300,000 homes in later years to hit 1.5 million homes over the parliament.

Housing targets will be set according to a new algorithm. Previously, housing targets were based on forecasts of population growth. A major flaw in these forecasts is that they failed to account for the fact that people might move to an area if housing were cheaper. An urban uplift, which added 35% to housing targets in the 20 largest urban cities, was brought in 2021, but had yet to be factored into most local plans as they were not up for renewal. This covered the urban core of most cities, but in the case of London covered the entire capital. New targets are based on two factors. First, there’s the baseline of 0.8% growth in the housing stock in every local authority. Second, this baseline 0.8% figure is multiplied by an affordability factor which raises targets in areas where house prices are high multiples of wages. This raises targets in most parts of the UK relative to existing targets. The only region to see a cut in their annual housing target is London, which sees its target cut from 98,000 to 81,000.

Let’s start with the positives.

Housing targets are far from an ideal system, but if they are to work there must be consequences for failing to plan to meet them. When mandatory housing targets were curbed, councils put the brakes on house building. Recent falls in housebuilding aren’t solely explained by the Gove ministry’s weakening of the penalties for missing housing targets – financial conditions and new building regulations like second staircase rules have also played a role – but it is clear that councils plan for fewer homes in their absence.

Higher targets are needed. It is twenty years since The Barker Review proposed a national target of 300,000 homes per year. Two decades of failing to meet that target has created a backlog of missing homes. The Centre for Cities suggests 450,000 per year for 25 years is roughly what’s needed to keep up with demand and clear the backlog. 370,000 homes per year is still short, but it's closer to what’s necessary.

Past assessments of housing need were essentially arbitrary. It was always absurd to base housing targets on population growth projections when population is itself a function of house building rates. All things being equal, more people will move to an area when housing is abundant and cheap. Likewise, more people will settle down and have kids when they can afford to buy a home. Affordability is an imperfect metric – an area could be unaffordable because wages are too low instead of housing being too expensive – but it at least has some relation to demand.

Still, Rayner’s new algorithm can and should be better on two key questions.

Does the new algorithm shift targets to the places where new homes will make the biggest possible contribution to growth?

Does the new algorithm shift targets to the places where new homes will provide the most relief to the people at the sharp end of the housing crisis?

Let’s start with the impact on economic growth. How does our new algorithm perform against a theoretical growth maximising algorithm?

It’s time for some spatial economics.

Economists have a simple answer to where new homes should go: where prices are highest. Or to be more precise, new homes should go in the places where house prices exceed build costs the most.

This is, of course, an oversimplification. It doesn’t account for the unpriced side effects of development such as road congestion, the need to build new infrastructure, or the potential loss of amenities (e.g. views). Yet neither do our existing housing targets. And each of these issues can and should be addressed through separate measures, whether those are congestion charges, levies on development, or targeted protections such as National Landscape status.

In an excellent (and highly readable) paper, economists Tim Leunig and Henry Overman write down a simple model to determine whether a city should have a bigger or smaller population. It starts with the intuition that cities exhibit economies of scale – agglomeration, in the economic lingo.

All things being equal, larger cities have a number of advantages over smaller cities.

Division of Labour: As Adam Smith observed, larger markets allow for deeper specialisation and division of labour. This applies to labour markets too. There are hyper-specialised jobs that can only exist in large cities.

Spillovers: Ideas spillover between nearby firms. One business may uncover a smart way to cut costs and improve productivity. Over drinks or dinner, managers at that business share the idea with managers at other businesses in different sectors. Alternatively, a worker from that business may get poached by a nearby business and share it with their new management.

Supply chains: Businesses find it easier to trade with and meet firms in their supply chain in large cities. For example, in London, a multinational food and drinks company’s headquarters may only be a short walk away from a range of highly specialised law firms, management consultancies and financial services businesses.

Generalist knowledge workers: The increased importance of knowledge workers who can move seamlessly from jobs in one industry to another (e.g. think of roles like HR) leads businesses demanding roughly similar skills to set up shop near each other. This, in turn, makes such places more attractive to workers.

Dual-earner households: The rise of dual-earner households means employers benefit from locating near other employers (even in completely separate industries) as workers decide where to locate based on the job opportunities for both themselves and their partner.

For all of the above reasons, larger cities tend to be more productive than smaller cities. You can see this in the chart below which plots GVA per head against city size. Larger cities, on average, are more productive. In France and Germany, for every 10% increase in city population there’s a corresponding 3% increase in productivity. Interestingly, this relationship is weaker in the UK with productivity only increasing by 0.9% for every 10% growth in population. One reason for this is that British cities, except London, tend to be smaller in practice (i.e. the share of workers who can get to the main employment area in 30 mins is much lower in Leeds than it is in Marseille.)

In the simple model that Leunig and Overman describe, workers’ wages grow as cities get larger (thus benefiting from the above advantages) and cities grow as long as workers experience a net wage premium from living in a city. In this model, the cost of housing increases when cities grow as scarce urban land is used up and building up becomes progressively more expensive. Flats for example, cost more to build per sq ft than houses. Each additional floor creates new challenges with the tallest buildings the most expensive on a square foot basis.

Housebuilding gradually shifts to the outskirts of the urban area where the time and financial cost of travelling to work grows.

At some point, the cost of adding new homes becomes greater than what a new resident might pay and cities reach their optimal population, at least for a point in time. If travel costs fall (e.g. because a new train line is built) or any of the factors I listed above making cities more productive become even more important, then cities will grow further.

The Planning Tax

Britain's major cities grew close to their current size in an era where planning restrictions were effectively non-existent. Yet today, development is tightly controlled by our planning system. In the past, the price of a new home was determined by three factors: the cost of buying land, the cost of construction, and profit for developers. There is now a fourth factor: the planning tax.

Economists Ed Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko note that in the US areas with only light-touch development controls and limited geographical constraints, this ratio between build costs (the first three factors) and house prices is close to 1. In other words, new supply is extremely responsive to demand. Existing supply is much less elastic – falls in housing demand do not lead to waves of demolition. So in some cases, such as in places like Detroit, which has experienced massive economic disruption (e.g. closure of auto-manufacturing plants), the ratio is below 1. Yet in the places where planning restrictions are most strict, such as San Francisco, the median house price-to-cost ratio was as high as 5.

In some parts of Britain, the ratio between build costs (per square metre) and house prices (per square metre) can be as high as 5.4. Think what that implies. A landowner would still profit from building a house on their lot even if they had to build it up and knock it down four times first.

In Oxford and Cambridge, the value of farmland can surge one thousand fold when planning permission is granted. In London, house prices are so high that it is possible to knock down existing council estates, rebuild them at higher densities, and use the revenue to fund massive upgrades in the social housing stock. This is a powerful signal to build more.

While it is true that new development can impose large costs on nearby homeowners in all sorts of ways, from congestion to pressure on local public services, these costs are not so large as to justify median price-to-build cost ratios as high as they are in many places. Development also brings benefits too. Local shops, cafes and pubs are more likely to survive when they have more customers nearby. Few people wish to be truly isolated from other housing.

It should be noted, by the way, that the planning tax is not merely the array of costs the planning system imposes on developers. The £125,000 or so cost of merely gathering the evidence to obtain an outline planning permission on a small development pushes up costs, but it isn’t the main cause. Nor is the planning tax the cost of complying with new building regulations, including second-staircase mandates for all mid-rise buildings. The real driver of the planning tax is the fact that new development is effectively banned on large swathes of land that could be profitably be developed, or, in the case of existing built-upon land, extended or redeveloped.

Location, Location, Location

Agglomeration isn’t the only factor that determines a city’s productivity levels and where businesses locate. In the past, it was access to soft water, local coal deposits or forests for firewood, or rivers and the sea that fuelled industry. Now, the main way goods get to our cities isn’t via rail or boat, but by road. The rise of containerisation means that goods move through today’s ports fast and are quickly on the road. Leunig and Overman note that access to the UK’s motorway network matters much more now, with most supermarket warehouses located along the M1-M6 and M4 corridors.

On top of road freight, more goods (by value) now enter Britain by air and most of those goods go via one of London’s airports. Airports matter too for the business travel essential to the modern service economy. There’s a reason why most of Britain’s major film studios are based to the West of London near Heathrow. Consequently, proximity to Heathrow, the UK’s largest airport, is associated with raised property values.

Another major factor businesses, particularly those in tech, consider when choosing where to headquarter or locate is access to skilled graduates and proximity to the cutting edge of scientific research. Prices tend to be higher in cities that are home to at least one major academic institution. Oxford and Cambridge are the clearest examples, but the same is true of York, Exeter, and Durham. All should expand.

Historic transport investments can play a major role too. Large investments in public transport such as Thameslink, Crossrail, and the Jubilee Line Extension have all shifted the UK’s economic centre of gravity closer to London and the South East. Research from Transport for London finds that in London property values within 500m distance of a tube station are 10.5% higher.

All of this suggests that the places where the ratio between median price-to-build are likely to be the highest will be in London and the wider South East, which is also what we observe in fact. It is in these locations where new homes will have the largest impacts on affordability and economic growth.

Yet, in general, London and the South East isn’t where new homes are built. Recent research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) finds the UK’s housing supply is extremely unresponsive to demand compared to other countries. In fact, supply is less than half as responsive to demand in the UK as it is in France or the US. IFS researcher David Sturrock notes “a rise in demand that would raise local house prices by 10% results in only 1.4% rise in housing stock, even over 25 years.”

The impact of all of this is that workers cannot afford to move to the places and jobs where they will be most productive. Once you factor in housing costs, many workers are financially better off in lower-paying jobs in affordable parts of the UK than in higher-paying jobs in the places where housing is most expensive.

This isn’t to say new homes shouldn’t be built in the North, by the way. Median price-to-build cost ratios are high in places like York and Manchester. In other parts of the North, where median prices are below build costs, such as Burnley, where the average home costs just £116k or Hartlepool (£130k), developers are unlikely to build enough homes to ensure the target is hit. In practice, development still proceeds in such areas, but what’s built is typically built with either subsidy or as high-end executive homes. While there will still be an impact on affordability, it’ll be limited and it will likely impose a number of unwelcome side-effects, such as increased car-dependency and loss of green space.

Nor will more homes in, say, Scunthorpe make housing more affordable elsewhere. By contrast, shortages in London and the South East have large knock-on effects on prices across the whole of the country. More homes in London will prevent its shortage spilling over on nearby towns and villages. A worker who otherwise would have been forced to leave the capital for, say, more affordable Winchester can instead stay put. Winchester becomes more affordable and fewer locals who work in Winchester are forced out to Eastleigh.

Such areas may still have major housing affordability challenges, it is just that relaxing planning constraints is unlikely to resolve them. Boosting local wages through better skills policy, increased R&D funding, and investments in infrastructure (e.g. faster connections to high-wage areas) are more promising approaches.

To summarise our whistle-stop tour of spatial economics:

All things being equal, market signals (median house prices) tell us where housebuilding will have the largest impact on productivity.

In the absence of planning constraints, the ratio between median house price-to-build costs should be close to 1.

Yet, Britain’s restrictive planning system means new housing supply is extremely unresponsive to demand.

Restrictions on where development can take place (e.g. the Green Belt) and how dense it can be (e.g height restrictions) have led median house price-to-build cost ratios to reach up to 5.4 in London, 1.92 in Cambridge, and 2 in many parts of the South East.

To maximise the impact of planning reform on growth, housing targets should allocate more homes in the areas where median house price-to-build cost ratios are the highest.

Is the new housing algorithm pro-growth?

Do the new targets allocate more housing to the areas where price-to-cost ratios are the highest? To answer this question, my colleague Ben Hopkinson has developed an alternative housing target algorithm. Instead of allocating housing targets on the basis of affordability ratios and a baseline housing stock increase of 0.8%, it allocates housing on the basis of median price-to-build costs, based on 2023 data on house prices by local authority and an estimate of regional build costs multiplied by the average floor area in each region.

This method is not, to be clear, a direct policy recommendation. There may be all sorts of reasons to divert from it: for example, some areas may simply lack the developable land to meet their target. However, it is useful in that it allows us to compare different methods as to how much they allocate housing to where it will boost growth the most.

So, what would happen?

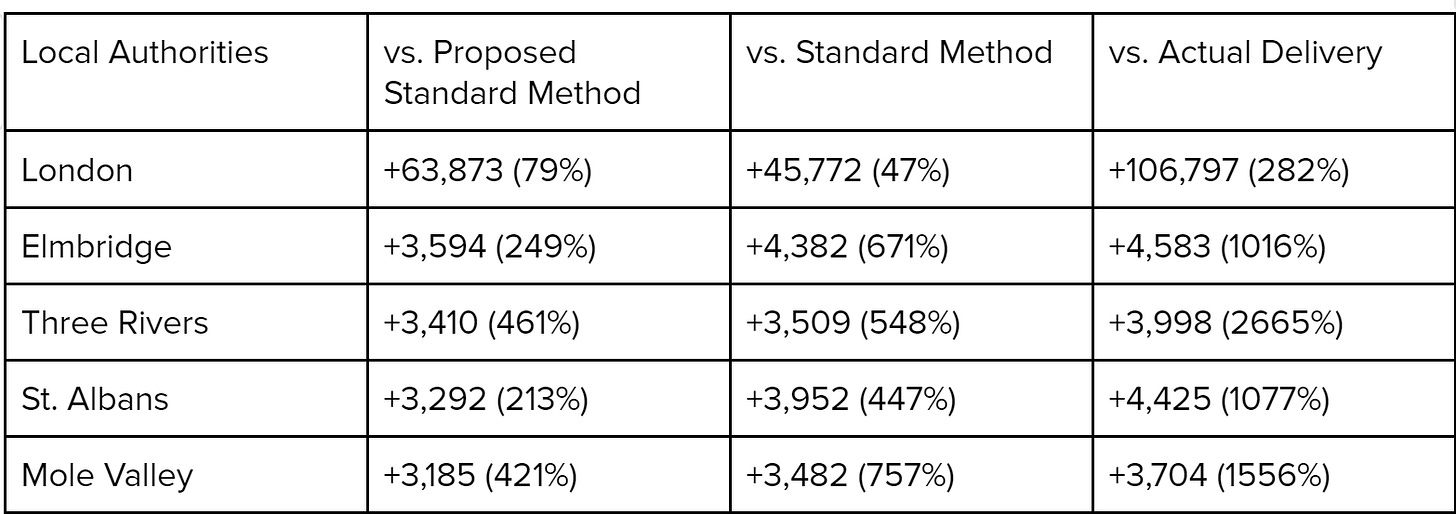

Housing targets would rise in London from 81,000 under the proposed standard method to 145,000 under the new method. London would move from delivering 22% of new homes to 39%. Targets would also increase in the wider South East, which would now be responsible for 28% of homes – compared to 19% under the proposed standard method. Targets would however fall substantially in most of the North and in particular, the North East. Oxford and Cambridge would also see a substantial uplift.

Where targets increase the most?

In some parts of the country, where houses cost less than build costs, mandatory housing targets would fall to zero. This isn’t to say housebuilding in such places ought to be prevented. Rather, it is to say there is relatively little national interest in overruling local councillors and forcing them to accept development that they think is otherwise inappropriate. The issue with this isn’t that a new estate built on the Green Belt in the North East is a net negative for Britain, but rather that it risks creating political opposition for little economic benefit.

Share of new homes delivered by region

How does the Government’s proposed method measure up against the last Government’s method based on population growth?

Overall, however, factoring affordability into housing targets means that under the new Government’s proposed method there’s a much stronger correlation between housing targets and where median price-to-build costs ratios are the highest than the last Government’s, which were solely based on population growth projection plus an urban uplift. The last Government’s targets were not binding either. Many councils massively underperformed their targets with little consequence. When you compare Rayner’s proposed method with actual housing delivery, it is a massive improvement. Actual delivery has almost no correlation with where economics tells us to build.

Whether you compare the new Government’s proposed method to the last Government’s method or to delivery, it’s clear that the changes announced by Housing Secretary Rayner are, on balance, an improvement.

However, not all changes made by Rayner and co. mean homes are built where economics tells us they are in highest demand.

One of the key changes in Rayner’s new algorithm is the removal of the urban uplift, which increased targets by 35% in England’s 20 largest urban areas. Under the past Government, London’s housing target was set to rise to 98,000. Under the proposed method, it falls to 82,000. However, the fall in London’s target is compensated for by an increase in targets across the wider South-East.

If the Government kept the higher target for London and reduced targets in the rest of the UK proportionally, the correlation between targets and market signals would be even greater. Importantly, any of these new targets would be an improvement over how housing is currently delivered in the UK, with almost no correlation to where housing would have the biggest impact on growth.

Correlation of targets to median price-to-build cost method

What about housing need?

The discussion so far has only covered housing targets in relation to their contribution to economic growth. Yet, housing matters not just because of its economic impact, but also because access to a safe, warm home is essential to living a decent life. The housing crisis isn’t just that people are priced out of the UK’s most productive places, it’s also that too many people in Britain are forced to sleep rough or in temporary accommodation. It’s that many people who would benefit massively from a secure social tenancy do not even bother signing up to the social housing waiting list because they have no hope of even reaching the top. And it’s that too many of our existing social properties are too often cold, damp and frankly, barely fit for human habitation.

Homelessness is a complex problem that cannot be reduced solely to supply. It means addressing addiction, the local housing allowance, and discrimination. But, supply helps. As the US chart below shows, homelessness is strongly linked to rent levels.

While it is unlikely anyone at risk of homelessness will buy or rent a market-rate new build, they still benefit due to moving chains. Restrictions on supply creates unnecessary conflict between upwardly-mobile young workers and long-term residents on low incomes. Think of the gentrifying young professional moving into a working class area. In the absence of new market-rate housing supply, they’ll bid up the rents of existing tenants putting them at risk of displacement.

One study of Helsinki’s housing market found that building one hundred centrally located market-rate homes created 60 vacancies in the middle of the market and 29 vacancies at the bottom of the market. This study isn’t an outlier either. Studies of the housing markets of San Francisco, New York and Germany have similar findings.

Recent research from housing campaigners Generation Rent found that rent rises were lowest in areas where the change in homes per 1,000 people was highest. In fact, they find that for every 20 extra homes per 1000 people, rent falls as a share of salaries by 2.8 percentage points.

Put simply, building more homes means fewer people are at risk of becoming homeless. So do the Government’s new housing targets allocate more housing to the areas where the least well-off are most vulnerable to homelessness?

To answer that question, we have created a second housing algorithm based on three key factors: the number of households in temporary accommodation or sleeping rough, the length of the social housing waiting list, and private rental sector affordability, which the ONS defines as rent being 30% or less of the median income of private renting households.

What does this social need algorithm tell us?

First, what’s striking is that while imperfect, there is still a correlation between building more homes where they will have the greatest growth impact and building more homes where they will have the largest benefit for the least well-off. Compared to the Proposed Standard Method and the old Standard method, a purely needs-based ratio means more homes in high-cost areas London, Cambridge, and Manchester. London’s housing need is so great that it alone needs to deliver over 105,000 new homes. Hardly surprising when one in 23 children in London are living in temporary accommodation.

Interestingly, areas with the highest social need tend to be urban, especially urban areas where the cost of housing is the highest, which means more people are likely to join social housing waiting lists and also risk homelessness.

Second, the Government’s new approach incorporating affordability in the setting of housing targets significantly increases the correlation between our needs-based distribution compared to the last government’s target and actual housing delivery.

Third, and again, cutting London’s housing target weakens the link between targets and need. If the Proposed Method was modified to uplift London’s annual target to 100,000, it would allocate housing to where it is most likely to reduce homelessness and help the least well-off.

Correlation of targets to needs-based method

Is a better method for allocating housing targets possible?

I think so. Labour’s new method for allocating housing, London target cut aside, is a clear improvement on what came before it. The new method ensures more homes are built in the places where new homes have the largest impact on growth and where new homes will help those at the sharp end of the housing crisis the most. However, it could be better still on both metrics.

Here’s our proposal for a new method.

Labour’s method starts from a baseline of 0.8% annual growth in the housing stock. The advantage of this approach is that compared to (inaccurate) population growth forecasts it assigns roughly the same amount of housing to similar areas with similar prices. The problem is, as Tim Leunig points out, starting with 0.8% stock growth limits the impact of affordability-based uplift.

There is a case for having some sort of housing stock growth factor to avoid saddling relatively sparse (but expensive areas) with large targets. I suspect in many of these areas – high house prices are as much a function of access to good employment opportunities as they are a function of them being generally pleasant places to live. Looking purely at median prices-to-build cost ratios would tell you that Kensington and Chelsea is massively under-delivering relative to other parts of London. Yet, high prices in Kensington and Chelsea are not purely due to the area’s employment opportunities (which are no better than many other central London boroughs), but also due to recreation, aesthetics, and luxury.

Yet, there is no specific reason to assign 0.8% growth, the current national average, as the baseline. Looking at market signals and metrics of housing distress, tell us that some areas should build a lot more than the existing national average, while others should probably build less. Reducing the 0.8% annual housing stock growth baseline to a lower figure and then strengthening the affordability multiplier would be an easy improvement.

This strategy is advocated by the housing campaign group PricedOut. They advocate that the Household Stock baseline should be cut to 0.46% while the affordability multiplier should be raised from 0.6 to 2.4 and should apply to affordability ratios above 5 (instead of 4). In essence, this would dramatically boost the role of the affordability multiplier and shift it even further towards the most unaffordable areas. This would keep the 370k annual target, but raise London’s share to around 100k.

Here’s an alternative approach.

Let’s take the annual target of 370,000 homes as a given and then use a formula to allocate those homes to where economic and social need is greatest.

To start, we replace the affordability multiplier with a multiplier based on two factors. Half of the new multiplier is based on median prices-to-build cost ratios. The other half is based on a combination of needs-based metrics (number of households in temporary accommodation or sleeping rough, the length of the social housing waiting list, and private sector rental affordability).

The formula1 is as follows:

Under this method London’s annual target rises to 125,189 (34% of all homes) and the rest of South East is tasked with delivering 85,756 homes per year (23% of all homes). The North’s share of the target is reduced though Greater Manchester’s overall target (10,386) is close to actual delivery (10,888). Targets in areas like Cheshire, Northumberland, and Dudley which increase massively under the Government’s proposed standard method are relatively flat or falling.

You can view an interactive map of all of the new suggested targets here.

Unsurprisingly, given how it was calculated, our new suggested algorithm allocates higher targets to the places where it will have the largest impact on productivity.

Correlations between Economic and Social Need Method and alternative approaches

What matters isn't just that the algorithm is generally correlated with need, but that is particularly correlated in the areas where the economic case for housing is strongest. On this front, our algorithm builds the homes in the areas with the severest housing shortages. The below table shows how many homes would be built in the areas within the highest decile of housing distress.

One somewhat surprising outcome of the new correlation is that it isn’t just better targeted towards growth opportunities and needs, it’s also targeted towards where voters support housing the most.

We found this by comparing the correlation of housing targets in our method, the standard method, the proposed method, and actual housing delivery using Ben Ansell’s MRP data on housing supply. Our new method recommends higher targets in high-cost cities, which also happens to be where support for new housing is the greatest. Interestingly, but perhaps not unsurprisingly given Labour’s willingness to pick fights with NIMBYs, the new Proposed Method is less correlated with voter support than the last Government’s standard method with its 35% uplift in London.

In the 10% of constituencies where support for new housing is highest, the new proposed targets deliver just 35,000 homes (less than 10% of total homes), while our proposed model delivers 82,000 (22% of total homes). These are the areas where you’re least likely to have fights with people opposed to new developments, so we should build more homes there to take advantage of the local support.

Correlation between local support for housing and targets

Is this achievable?

When Housing Secretary Rayner announced the new targets in Parliament, she dismissed the last Government’s 100,000 home annual target for London as unachievable. Our method suggests a similarly high target of 125,000 for London. Is it achievable?

I think so. 125,000 homes per year in London is equivalent to building 3.3% of London's existing housing stock. British cities have achieved this in the past. In fact, Britain as a whole achieved it in the 1930s. Around the world, this level of building isn’t unheard of. Major reforms to the zoning system of Auckland (population 1.7m) delivered 21,400 homes in 2022, the equivalent of 116,000 homes in London. Economists assess that rents were a third lower in Auckland than they otherwise would have been as a result of this policy, such a fall in London would save an average couple £6,000 a year.

Austin, Texas (population 2.4m) is another good example. In 2022, they consented 42,365 homes, the per capita equivalent of London building 160,000. Last year, rents in Austin fell by 7%, with residents reporting being offered rent decreases if they renewed their lease. The Tokyo Metropolis area (population 13.5m in 2015) averaged building 155,000 homes per year from 1995 to 2015. That’s the equivalent of London building 103,000 homes every year for two decades.

There are examples within London too. Newham (population 355,000) built around 35,000 homes over the last decade. If the rest of London built at the same annual rate (per capita) as Newham then it’d be equivalent to 89,000 homes per year.

It is true London’s existing housing delivery is far below not only Gove’s 98,000 or Rayner’s 82,000, but even its current 52,000 target. Yet, this isn’t due to the fact development is unviable in London. Rather, it is the result of restrictive planning rules and a failure to allocate enough land for housing.

There are massive opportunities to build new homes in London. For instance, London could adopt an Auckland-style upzoning policy where six-storey (or eight-storeys within zone one) development near tube and train stations is permitted by right. At the very least, the government should implement street votes, which would create a massive incentive for individual streets to approve denser developments in low-density neighbourhoods with fast connections to central London.

Estate renewal is another major opportunity. London is full of low-density council housing estates in highly desirable areas. Rebuilding them at a higher densities with private housing could expand and upgrade London’s housing stock while delivering 100,000s of homes. A national policy to call in and approve any estate renewal project with majority resident support would eliminate planning uncertainty and mean more of these projects would come forward.

And then there’s the matter of golf courses. London, absurdly, has 95 full-size golf courses within its city limits. Taken together, the land taken up by London’s golf courses is more than double the size of the City of Westminster. Building merely on half the land of the golf courses within walking distance to a tube or train station at gentle densities would unlock 60,000 homes.

What are targets good for?

It is worth thinking about why housing targets are necessary.

In her speech, Rayner made a virtue of the fact that her new algorithm ended the state of affairs where some councils had targets massively below their actual housing delivery. Yet, the point of mandatory housing targets is in the name. They’re there to get councils to do what they otherwise won’t do. It is the national interest asserting itself over local decision making. Let’s be clear, an algorithm that sets low targets in the North isn’t an algorithm that caps the ambition of the North. Northern local authorities remain free to plan for more homes than their target.

It may seem absurd now, but in the past politicians in Westminster believed that local authorities were planning for way too many homes. The result was a new system of planning where the incentives for towns and cities to permit new private development were stripped away. In the long-run, our goal should be to fix this incentive mismatch so mandatory targets are not necessary.

But the issue is as it stands local authorities in London and the South East lack those incentives and consistently fail to plan for and deliver enough homes despite the market screaming at the top of its lungs: “Build more homes right here!”

Mandatory targets are, by their very nature, combative. Targets mean a fight between local authorities and Whitehall. Every single fight will expend some of the Government’s political capital on planning. Britain’s post-war history is littered with reform efforts that run out of steam or fall apart in the face of committed local opposition. It is vital then that the fights Labour picks on planning are ones where new housing has the largest impact on economic opportunity and poverty – where winning is worth it.

If Economic Need is less than 0, then Economic Need should be set to 0 to avoid the suggestion that negative homes should be built. This happens when the average house price is less than the average build cost. The 28,800,000 figure refers to the sum of each local authority’s house prices- build costs. This allows for a proportional distribution of new housing based on where the differences between house prices and build costs are the largest without having all of the local authority’s house prices-build costs.

On calculating private rental affordability: 1.2 refers to the median number of economically active adults per household (source- table 16). 0.3 refers to the affordability threshold set by the ONS, i.e. whenever median annual rent divided by household income is greater than 30%, rent is unaffordable. When Median Rent divided by median household income is less than 0.3 the numerator should be set to 0. In the denominator, 18.24 refers to the sum of each local authority’s rental affordability, which allows for a proportional distribution of new housing similar to Economic Need.

Terrific piece, Ben, thank you.

To highlight one additional area where one could question assumptions, it is how the Spatial Economics elements are changed radically in our global and digital and remote working world. Each of the four elements you note are focussed on knowledge workers and how having them close together in major cities has historically created benefits in terms of economic growth.

Now consider through the lens of being location agnostic:

- Division of Labour - when your people work anywhere (both within the country (outside commuter range) or anywhere in the world), then this makes a difference. I have multiple clients, friends, family who as routine, lead teams that work and live globally

- Spillovers. You note "over drinks or dinner". As we know, socialising in person happens less and less in our modern times, though yes, this one still has strength, with people connecting in person and so creating serendipities. On that note, how about joining a monthly Walkabout as my +1? 5pm on 4th Tuesday of the month behind Green Park station. No agenda, simply engineering serendipities through walking and talking

- Supply Chains. When it comes to knowledge workers, the idea that one head office being close to another one creates economic benefits now seems strangely archaic. City centre offices for many global firms are increasingly an anachronism in our globally connected age. We live and work on Teams and Zoom and by email, not in offices.

- Dual earner households. Again, with knowledge workers they have more and more choice over where to live (and, when having children), to create freedom via affordable housing and living.

All of that said, I have worked remotely and with global clients (mostly on zoom, but yes, I get on aircraft to see them in person from time to time), but I live in London. Why? Almost everybody in my global client base travels to and through London for meetings at least a few times per year, as well as every thinker or writer I'd like to go and see talk or present. Living in London keeps all of that readily accessible to me, even when (as at the current time) none of my clients are in the UK.