Anatomy of a Planning Refusal

When 9,000 pages isn’t enough detail

In Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, the protagonist Yossarian learns that any pilot who requests a mental evaluation, in the hope of being found not sane enough to fly and hence avoid dangerous missions, will be unsuccessful because their fear of death is evidence of sanity. Catch-22 is a work of satire, yet it seems to accurately describe the process of obtaining planning permission in Hackney.

The economic case for building 80,500 sqm of commercial, lab, and creative space (plus 40 homes) is clear cut. The impressive thing about the proposed Shoreditch Works development in Hackney is they’ve figured out a way to do it that the public seems to actually like. The public might like it, but their opinion isn’t the important one. Hackney’s planning officers have recommended that councillors refuse the scheme planning permission.

To my untrained eye, Shoreditch Works is exactly the sort of thing we should be building. Why then are Hackney’s planning officers recommending blocking the scheme? To find out I have read their full report and looked through hundreds of documents submitted by the developers. It was an education in just how broken the planning process in Britain’s most expensive city is.

In their quest for planning permission, developers submitted 9,084 pages across 450 documents.1 There is a sunlight and overshadowing report; an affordable workplace strategy and 975 pages dedicated to an environmental impact assessment (for an exclusively brownfield development a stone’s throw from the City’s glass and steel skyscrapers). All of this was insufficient in the view of Hackney’s planners.

“The level of detail submitted to support the scheme is, for many elements, that which would be expected of an outline scheme, rather than a full application.” – Hackney Council Planning Officer Report

Bad Policy

When Britain Remade looked at planning applications from the 1930s, we discovered they were remarkably short - a few pages at most. Most of London’s buildings, including almost all of the buildings that Hackney council seeks to conserve, were built under a remarkably simple planning regime.

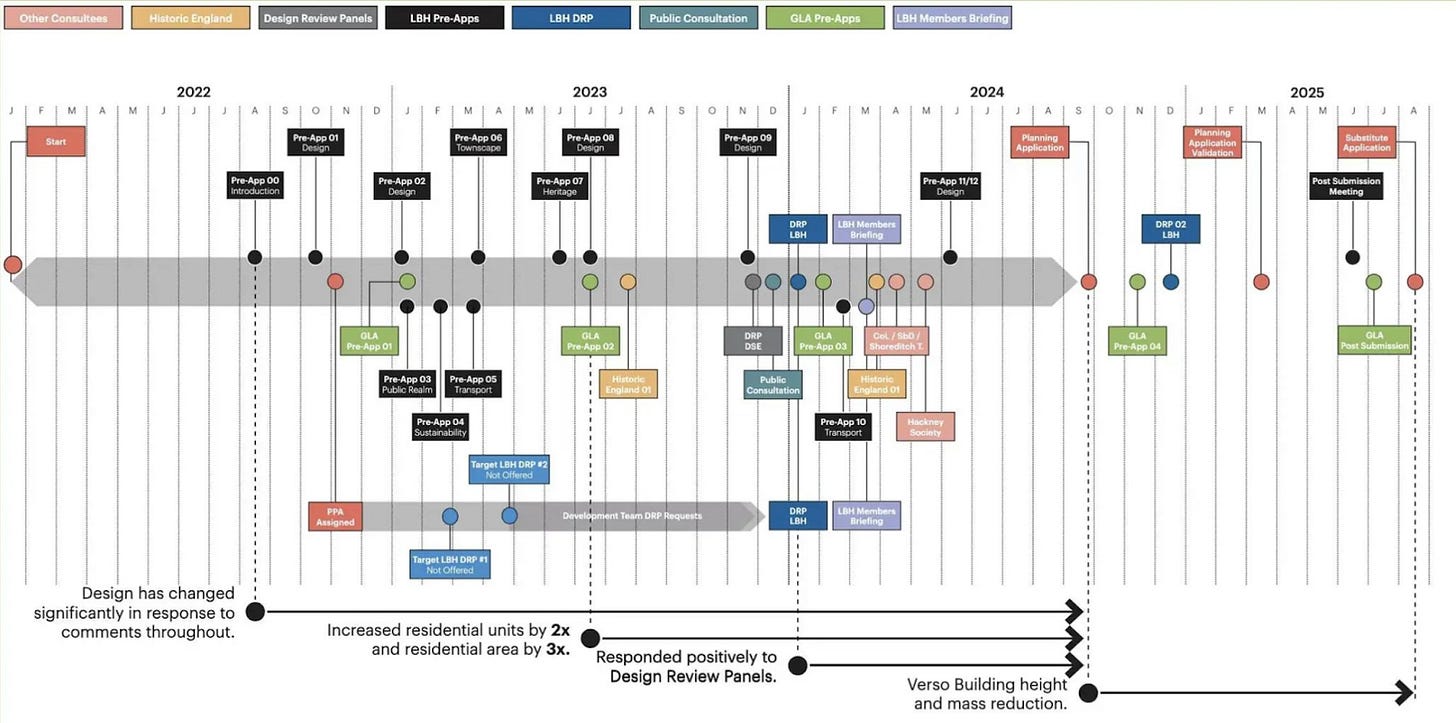

How, then, can a planning application stretch to 9,084 pages? Well for Shoreditch Works, the applicant had to demonstrate compliance with 42 separate Hackney policies, 75 separate London Plan policies, the Hackney Borough Site Allocations Plan, five other separate sets of standards and policy frameworks, two sets of ‘emerging’ unfinalised policies, plus all relevant national legislation and guidance. That is before getting into supplementary planning documents, technical guidance, and informal expectations. This is a huge task not just for developers, but for planners as well. The system is set up to be adversarial, slow (4 years and counting), and extraordinarily expensive before a single brick is laid.

Be afraid (of your own shadows)

Many of the policies themselves are either poorly suited to central London or reflect objectives that are questionable.

A good example is daylight and sunlight. One of the objections planners raised was that parts of the new development would not receive enough natural light. Someone choosing to live in a dense, central London location might reasonably decide that access to jobs, transport, and amenities matters more than generous sunlight. They might even just prefer paying a bit less for less natural light, a reasonable choice adults should be allowed to make for themselves. Planning policy disagrees.

Rules to prevent overshadowing are not inherently irrational. Much of London was built under rules designed to prevent development from casting shadows or overlooking nearby properties. This is a classic case of intervention to prevent market failure, where the costs of an economic activity fall upon non-consenting third parties.

But strikingly, the recommendation for rejection notes that the main reason for the lack of natural light is the shadows cast by other parts of the same development. In other words, a development can be penalised for casting shadows on itself. Buildings are required to be scared of their own shadows. This issue was not ultimately the decisive reason for refusal, but it shows how detached some policy tests are from basic economics.

Is it green enough?

Climate policy provides an even starker example. A major theme of the refusal recommendation is that the developers have not provided sufficient evidence (across some 9,084 pages) that the scheme will reduce carbon emissions.

Reducing emissions is a noble goal, but blocking new homes in London is self-defeating. Hackney already has among the lowest per capita emissions in the country. Thanks to high quality public transport and the close proximity of jobs and services, only 8.5 percent of journeys by Hackney residents are made by car or motorbike. The scheme provides no parking other than for disabled people, so residents and workers would be even less car dependent. On top of that, dense urban form, widespread use of flats and terraced housing, and the urban heat island effect mean Hackney residents use far less heating than average. As a result, the average Hackney resident’s transport and domestic emissions are less than half the UK average.

If Hackney genuinely cares about climate change, the most effective thing it can do is allow more people to live and work there. Density is climate policy. If Hackney had the same population density as central Paris, it would accommodate around 100,000 additional residents. If those people would otherwise have average UK carbon emissions, housing them in Hackney would save about 154,556 tonnes of carbon every year. That is more than all the shops and offices in Hackney emit combined, and more than the emissions from everyone in the borough taking a return flight to Spain.

Planning policy does not allow this logic to be considered at all. Instead, it fixates on narrow, site-level metrics that ignore displacement. Councils in rural or semi-rural areas are often criticised for declaring climate emergencies while blocking renewable energy projects. But big-city councils that declare climate emergencies while actively restricting the supply of low-carbon urban lifestyles through housing and employment constraints are guilty of the same hypocrisy. By ignoring where people and jobs go if they are blocked in Hackney, the council can trumpet its green credentials all the while increasing national and global emissions.

The same narrow thinking appears in the treatment of embodied carbon and materials. A large section of the refusal focuses on the fact that significant amounts of existing building fabric would be replaced with new materials, and on technical arguments over what percentage of materials should count as reused. But this again takes an artificially limited view of environmental harm. The 4,150 people who would work on this site will work somewhere else if they do not work here. Given the site’s location, it is reasonable to estimate that virtually none of them would commute by car. This development, in fact, removes parking spaces. The council itself notes that the area has a PTAL rating of 6b, the highest possible level of public transport accessibility.

If this economic activity is displaced elsewhere it will almost certainly be a more car dependent place. None of this is allowed to enter the assessment. Yet dense urban office space, closer to housing leads to low car-use and lower heating demand, supporting the most sustainable lifestyles available in the UK.

Catch-22

The problem is not just that many individual planning policies are poorly designed. It is that they interact with each other in ways that make compliance close to impossible. Even when individual objectives are sensible in isolation, taken together they form a system that blocks any development.

The rejection explicitly recognises that Hackney does not build enough homes and will need to step up delivery in coming years. This is a correct observation though Hackney is far from the worst offender in inner London.

However, it then uses this fact as a reason to refuse the application. That is despite the scheme increasing the number of homes on the site from 38 to 78, and increasing the number of social rent homes from zero to sixteen. A development that more than doubles housing provision is deemed unacceptable because it does not provide enough housing. The practical result is that instead of around forty new homes, there will be none at all. At first glance, this looks like a clear case of letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

However, the scheme is primarily an office and commercial development, providing space for around 4,150 jobs by the developer’s estimates. A natural response might be to suggest reducing office space and increasing housing. One problem:the site is designated a “Priority Office Area” in Hackney’s Local Plan.

The red square marks the approximate location of the development, not to scale.

But the designation does not make it easier for this project to get approval. Instead, it is used as a reason to refuse the scheme, because it does not meet specific requirements around the provision of subsidised office space. The development, as well as building a huge amount of high quality office space that would push down local market prices, was committed to increasing the amount of low cost office space on the site relative to present levels. But not by enough to satisfy Hackney’s policies.

So the planners think the building needs more subsidised office space and more housing. A solution to this might be to make the building bigger.

But this option is closed off. The site sits within the South Shoreditch Conservation Area. A key objective of the conservation designation is to preserve the contrast between the taller buildings of the City of London and the lower-rise character of Shoreditch. Height therefore becomes a problem in itself. The rejection states that elements of the scheme are already too tall in at least 30 paragraphs.

The developer is therefore faced with a set of constraints that cannot all be satisfied at the same time.

The scheme does not deliver enough housing.

It cannot easily deliver more housing, because it is already too tall.

It is expected to prioritise offices, because it is in a Priority Office Area.

But it must also meet additional requirements that reduce the amount of viable, market-facing commercial space.

The scheme must be profitable for the developer investing millions into it.

The rejection itself acknowledges that this is unlikely. Reducing market office space, increasing housing, and complying with additional obligations would render it unbuildable. A policy objective that Hackney should build more homes is taken to an extreme where, in combination with other policies, it results in no homes being built at all.

The outcome is a form of policy deadlock. The development is simultaneously too tall and not tall enough, provides too much office space and not enough, and is required to deliver additional social objectives that make it financially impossible to construct. It becomes a kind of Schrödinger’s building: too big and too small at the same time.

A similar contradiction is displayed on green roofs. Parts of the scheme include roof-level green space for residents. A reasonable person might think that someone choosing to live in one of the most built-up parts of Britain has already decided that private access to green space is not their top priority. Planning policy does not allow this judgement to be made.

At the same time, biodiversity rules apply. The biodiversity officer notes that resident access to green roofs may disturb wildlife. The result is that some parts of the council argue that residents do not have enough access to green space, while others argue that they have too much. Both positions follow policy correctly. The problem is that when policy is applied correctly, access to green space and improving biodiversity become mutually exclusive. While ultimately the relevant officers in both of these cases didn’t think these were sufficient reasons to reject the application it further shows how complying with all of the rules is often completely impossible.

If a policy framework produces outcomes where sensible improvements cannot be made because rules cancel each other out, the problem is not the applicant or even the planning officers but the policy.

Planners versus the people

A central reason given for refusal is that the scheme is considered unacceptable in design, conservation and heritage terms. This judgement rests heavily not on clear, objective harms, but on the aesthetic preferences of planners and the design review process.

The planning officer goes out of their way to criticise the fact that the development uses a ‘single era of 21st Century design, by one Architecture practice.’ Consistency of design is treated as a flaw. The implication is that a coherent architectural language, applied across a large site, is itself suspicious. This is striking given that the style adopted is one that ordinary people tend to like and we have opinion polling evidence they much prefer the new design to the existing building.

The purpose of the planning system, at least as applied here, does not appear to be to enable buildings that the public finds attractive. Instead, it seems to prioritise the tastes of a narrow professional class. Earlier in the documents, the scheme is criticised for not “going with the grain” of the surrounding buildings. Yet elsewhere it is implied that the scheme should not even go with the grain of itself, and should instead fragment into multiple architectural approaches. It is difficult not to suspect that had the scheme done this, it would have been criticised for incoherence instead.

The treatment of heritage reinforces the impression there is little regard to the public’s wellbeing. The developers point out that the scheme would make several existing heritage buildings visible to the public for the first time. Officers acknowledge this, but dismiss it as a very minor benefit. Heritage, in this framing, exists for its own sake, not for people to see, enjoy, or engage with. Visibility and public experience count for remarkably little.

The Hackney Design Review Panel is heavily relied upon in the refusal. It is described as being critical of the “general architecture and massing of the Verso building, the scale and grain of St James’s House, the quality of the public realm and overall the public benefits delivered by the scheme”. These are sweeping judgements. What is notable is what is missing. Nowhere is there any engagement with what normal Hackney residents would think.

Members of the panel are paid by the council: £450 per meeting for the chair, and up to £200 per meeting for other members, at £50 per hour. There appear to have been at least three meetings, and possibly more.

One of the rotating chairs of the panel works at Cazenove Architects who work in a style that produces a mix of strikingly beautiful modern buildings and what look like corrugated sheds (readers’ views may vary). However, regardless of the merits it is not clear that any of their work pays much attention to going with the grain with the existing building, especially when working on council projects which can be seen in the extension built on buildings below. It feels very do as I say, not as I do, from the panel

These design judgements are not confined to the panel. The planning officer’s own commentary reveals a broader hostility to dense urban development. There is a lengthy section lamenting the impact of existing City of London buildings on views from the Honourable Artillery Company army barracks. The officer describes nearby City buildings as “incongruous and imposing”, despite the fact that they are outside Hackney and form part of the UK’s main financial district. One hopes the soldiers who work at this army barracks are robust enough to not be upset by viewing some tall buildings from their sports pitches.

This mindset matters, because it shapes discretionary judgement. The development is subjected to thousands of words of criticism about its alleged lack of architectural quality. These critiques amount largely to the personal opinions of other architects and planning officers. The fact that when the public are actually asked in a carefully controlled national poll, 78% prefer the proposed building to the old one is treated as irrelevant.

Officers accept that none of the buildings proposed for demolition are of architectural or historic interest in their own right. Yet they still find arguments to keep them stating that they are ‘reflective of their era’ ignoring the fact that every building, by definition, reflects the period in which it was built.

What this section reveals is not a neutral application of design standards, but a system in which subjective preferences, professional gatekeeping, a deep suspicion of popular taste and massive status quo bias are given decisive power. This is yet another set of requirements that the developer is expected to satisfy.

What approval would have meant

Even if the councillors do overrule planning officers and approve the scheme, this does not mark the end of the process. The documents make clear that approval would merely have opened the door to further design changes, additional reports, and significant new financial demands. The idea that planning permission provides certainty is largely illusory.

Across the refusal documents, there are at least fifteen separate points where officers state that further work, further money, or further changes would have been required had the scheme gone ahead. Approval would not have fixed the scheme; it would simply have allowed the next phase of negotiation and extraction to begin.

Officers indicate that publicly accessible routes through the site would need to be revisited and potentially redesigned. A programme of “social, cultural and business uses” would have been required to be secured through the legal agreement, to ensure that parts of the scheme functioned in a way definable as Affordable Workspace. In other words, even after permission, the basic shape and use of the scheme would still have been open to renegotiation.

Alongside this came a long list of financial obligations, many of them small in isolation but significant in aggregate, and all layered on top of costs already agreed.

The council’s biodiversity officer estimates that the development would result in a 1,375 percent increase in biodiversity. Despite this, the developer would still be required to pay £17,309 to monitor whether biodiversity net gain actually occurs.

The developers are expected to pay £352,687 for employment schemes related to construction and £1,320,451 for employment schemes related to the end use of the buildings. These may be worthy objectives, but it is far from clear why property developers are the appropriate people to pay for them.

Further charges include £2,000 to monitor the provision of cargo bike delivery hubs and other transport measures, £10,000 as a contribution to an electric vehicle car club plus £60 of credit for every resident, £9,000 to monitor the travel plan, and £17,500 to monitor the construction management plan.

All of this sits on top of substantial payments already agreed as part of the Community Infrastructure levy: £4,034,134 to Hackney Council and £8,564,287 to the Mayor of London.The transport element reveals another structural problem. The developers had already agreed to contribute £850,000 to Transport for London for road and cycling improvements. However, the planning documents make clear that Hackney Council would have required the developers to push back on TfL’s demands as a condition of approval, because TfL extracting too much money would reduce what the council itself could secure. Paying off one arm of the state leaves less money for another.

It ain’t over yet…

The good news is that this isn’t the end of the road for the Shoreditch Works scheme.

The application now goes to the Hackney Planning Subcommittee, where tonight(!) councillors can choose to overrule the officer recommendation. Whatever they decide tonight is unlikely to be the end of the process. If approved, many of the costs, conditions and renegotiations described above will still apply and may render the project unviable. If rejected, the Mayor of London is likely to take an interest.

The system is clearly broken. But in the system as it is, public engagement still matters and if you live or work in Hackney, writing to councillors today (list here) or attending the meeting can make a real difference. Planning decisions are often presented as technical and inevitable, but they are ultimately political choices about whether homes, jobs and investment are allowed to happen at all.

A handful of documents do appear to be duplicated however many more appear to have missing earlier versions, so this is likely a low end estimate. All documents downloaded from the Hackney Council Website

🎯 And the same dynamics are at play over and over again with every planning application across the country.

it's just appalling

we are stuck in a dystopian comedy of errors