Labour are finally taking the housing shortage seriously

Is this Labour’s biggest pro-growth move?

To get an idea of how radical yesterday’s changes to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) are, consider this. Every time a new NPPF is published for the first time, it is as a track changes document. You can see each and every specific footnote that has been struck-out. Campaigns would be waged against specific footnotes, like footnote 58, which effectively banned onshore wind in England. And people would celebrate when offending wording was literally crossed-out. Yesterday’s draft NPPF was different. There were no track changes because the document was a complete rewrite.

I have been critical of how the Government has let rhetoric run ahead of policy. It is clear from their speeches that Keir Starmer, Rachel Reeves, and Steve Reed really do get how bad England’s planning system is and that there’s no more important lever to pull to boost growth than planning reform. Yet, Labour’s policies in office have, until yesterday, failed to match that rhetoric. There have been plenty of good measures, but far from enough to reach the Government’s 1.5m home target. In fact, without changes in policy, Labour won’t just miss their manifesto target, they won’t even outbuild the last Government.

The NPPF changes published yesterday were of a different magnitude. It is not just the most radical change in the history of the NPPF (the first one was published in 2012), it is quite possibly the most radically pro-development planning document published since 1947.

The ‘Default Yes’

The most radical measure, by far, was a new beefed-up permanent Presumption in Favour of Sustainable (or as the consultation puts it ‘suitably located development’). At the moment, councils that are failing to meet their housing targets or have out-of-date plans are restricted in their ability to block new homes. Unless there are ‘adverse effects [that] significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits’ or protected-site constraints (e.g. it is in a national park), proposals for new development must be accepted.

Even if a political planning committee rejects the proposal, the developer can still escalate it to the planning inspectorate where they have a good chance of winning on appeal. This is what people are referring to when they talk about ‘planning by appeal’.

The NPPF changes that in three key ways. First, the stronger presumption applies whether or not a council has met its targets. Second, significantly has been replaced with substantially, which based on dictionary definitions suggests a stronger policy. Third, the presumption is defined much more explicitly. Within towns and cities, development should be approved as long as it complies with new national decision-making policies. The really big change, however, is what it means for developments outside of settlements.

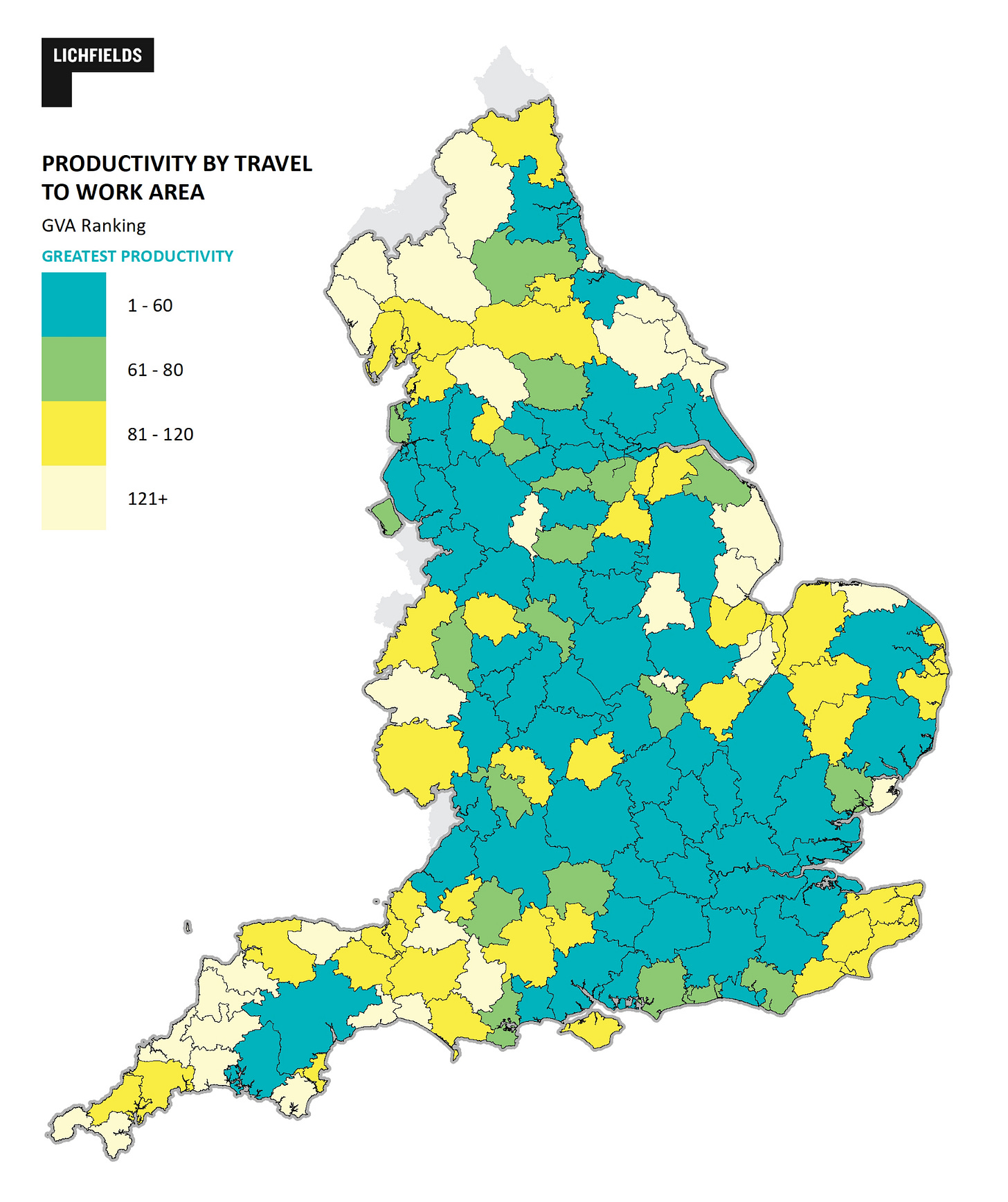

There will be a ‘default yes’ in favour of new homes and mixed-use developments within walking distance (800m) of train, tube and tram stations. This will apply both to new homes near stations within cities and towns, but also crucially to well-connected stations outside cities and towns, including on green belt land. In the draft NPPF, well-connected is defined as having a frequent service (at least four trains an hour) to one of Britain’s 60 most-productive Travel To Work Areas.

To be clear, this isn’t a policy for sprawl. New developments must exceed minimum density standards of 40dph (dwelling per hectare) for all stations and 50dph for the best connected stations. There is an expectation that in urban areas even higher densities will be reached.

It is hard to overstate how big this is. The Government could easily exceed its 1.5 million home target for the Parliament just by building near stations in London and the South East. And that doesn’t even adjust for the higher densities sought in urban areas. If it survives consultation, and you best believe there will be an almighty fight, it will be the single most powerful pro-supply move in post-war Britain.

This is radical by British standards, but there is precedent. New Zealand’s most expensive cities have built at a clip since successive governments brought in measures to create a similar ‘default yes’ to densification near city centres and busy transport corridors. One study suggested that over six years the policy cut Auckland’s rents by nearly a third. If the same happened in the capital, the average Londoner would save £9,000 each year.

California, one of the few places with a housing crisis as bad as our own, is trying something similar. They have just passed SB79, a major reform that will permit up to nine-storey development near bus, tube, and train stations.

There will be challenges. Building near train stations will mean busier trains. And as a regular commuter on the Brighton Mainline every day I see a system pushed to the limit. People will be much less welcoming of their new neighbours when their face is pressed against their armpit on a standing room-only 7.32.

When planning permission is granted, land values shoot up. Some of that uplift can be captured by local authorities via Section 106 agreements. The Government’s past rhetoric suggests that the first port of call for that cash will be council (or otherwise subsidised) housing. If this policy is to succeed, that will need to change, a big chunk of that uplift must go towards renewing our creaking transport infrastructure.

Granny Flats, Extensions and more

YIMBYs would find it hard to complain if the ‘default Yes’ near train stations was all there was in the new NPPF, yet there’s another policy within the framework that could be just as powerful.

One of the biggest opportunities to build more homes (or at least, increase Britain’s total floorspace) is to make better use of our existing homes. Policy L2 in the draft NPPF would give substantial weight to the benefits of development that:

“…[Creates] additional homes within settlements by using the airspace above existing residential and commercial premises, or through sensitive redevelopment or additional development within existing plots (including, but not limited to, the addition of mansard roofs, proposals to fill gaps in the existing roof line, the introduction of higher buildings at street corners and additional units within residential curtilages).”

Like the railway policy, this could be huge. Create Streets estimate points that a recent policy to allow mansard roof extensions in one Tower Hamlets neighbourhood added 300 extra bedrooms. In another paper, they estimate that if just 10% of the 4.7 million pre-1919 homes in England added mansard floors, it would create almost a million new bedrooms without a single demolition being necessary.

Granny flats (known as accessory dwelling units, or ADUs in the US) are another example of the type of gentle suburban intensification this policy would allow. A reform in California made it much easier for households with big plots to build small homes in their backyard. In just five years, permits were granted for over 100,000 new ADUs. Most permits were built out quickly, often within a year. One third of new homes built in Los Angeles are now ADUs.

This isn’t just about building new homes. One big benefit of letting people build granny flats in their garden is that granny (or grandad) can live nearby. At a time when social care costs grow ever larger and nearly a million elderly people experience loneliness on a regular basis, that must be a good thing.

There are limits. This isn’t an automatic yes. Councils can still say no, if they have good reasons, though they might still lose on appeal. Neighbours’ access to daylight and privacy must be taken into account. Extensions must be consistent with the street scene. And there are limits to how much of a garden you can grab (“of the non-developed area within the building curtilage”).

Proportion in Planning?

The big debate in the run-up was over the role of the National Development Management Policies – in essence, new national policies that would directly override council policies on things ranging from density around stations to flood risk. Britain Remade and others such as the Centre for Cities, wanted to see them on a statutory footing. We didn’t get that for complicated reasons, but we got the next best thing. Where national policies and local policies conflict, national policies now carry much more weight.

One way councils restrict development is by gold-plating national standards. A major redevelopment of an industrial site in Camden was blocked because the development was not exemplary in terms of embedded carbon and recycling. The new decision-making principles through the NPPF make that sort of gold-plating much harder.

The end result is our planning system is less about the judgement of expert local planners, and more about compliance with clearer national rules. It should reduce uncertainty and cut bureaucracy. This is particularly important for smaller developers, who are less able to navigate planning risk, delays, and afford upfront costs. Smaller developers tend to build their permissions out at a much faster pace so making life easier for them is really essential to hitting the 1.5m target.

One of the key decision-making principles is around proportionality and the information required for planning applications. This is now based on a national list, not one that varies by council. Councils could in theory require more information, but the scope for this is limited. And crucially, they need to keep evidence requests proportionate. The rules now distinguish between small, medium, and large developments. This embeds common-sense into the system. Building a mansion block isn’t the same as regenerating a 1,000 home council estate: they shouldn’t be treated in the same way.

Why does this matter? Well, there are many parts of Britain where development is controversial. Planning applications for new homes on Green Belt land near train stations are rare because until yesterday policy was relatively clear: don’t build here. Yet even the most uncontroversial projects – the right homes in the right places - must overcome massive hurdles.

Take recent plans in London to build 14 flats a short walk from the Blackhorse Road Victoria Line station. The flats were to be built on brownfield land near light industrial land (some of London’s best breweries are 5 minutes away). The block would not be the tallest on the street. In fact, it would be slightly shorter than a neighbouring block. The London Plan classifies it as an ‘Opportunity Area’. It is, in short, exactly the sort that should be approved and I am sure it eventually will.

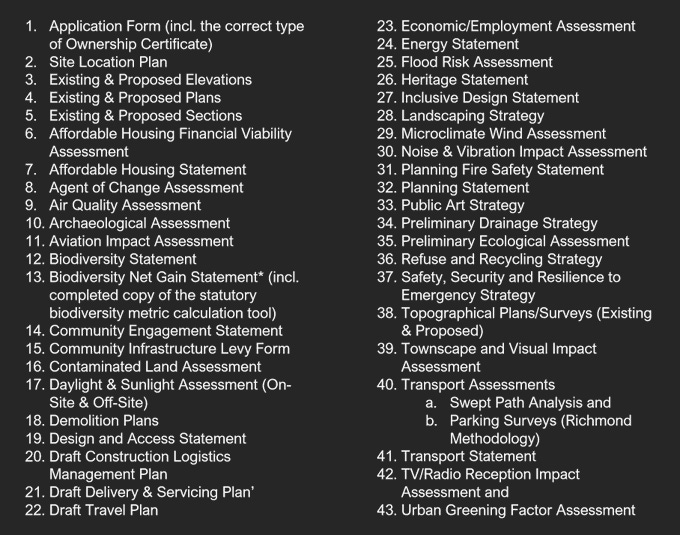

Yet to get planning permission, the developer was forced to carry out around forty or so separate assessments. Their full planning application, including all supporting documents, was longer than Tolstoy’s War and Peace. This isn’t a unique story. All over England this is the case. London, however, is the worst place for it. YIMBY architect Russell Curtis recently listed 43 assessments that were required before a planning application could be submitted for a small development in Croydon.

That’s not the only move designed to help SMEs. There’s a new category of ‘medium development’ defined as 10-49 homes on sites smaller than 2.5 hectares. There are two big areas where this means less regulation.

Biodiversity Net Gain

New developments in Britain are required not only to mitigate their impacts on nature, but also to provide a 10% net gain in biodiversity. The intention of the policy was to kickstart a market for private nature recovery, and, in that sense, it has succeeded. There are now plenty of landowners bringing forward land for nature recovery.

However, it has added to the burden on housebuilding. Almost all new housing developments are required to carry out a biodiversity net gain (BNG) assessment. Where possible, they must deliver biodiversity net gains on site. If they can’t generate gains on-site (and can prove that) they are able to buy off-the-shelf BNG credits.

For smaller developments, it is a real problem. It is harder to deliver a net gain on a smaller plot, or in denser urban areas. Designing BNG schemes is complicated and there are economies of scale that can’t be accessed. Evidencing that a scheme would work, or that on-site gains can’t be found is expensive and time-consuming.

To unblock it, the Government consulted on exempting all sites smaller than half a hectare from the scheme. At the dispatch box, Pennycook revealed that this had been watered down to 0.2 hectares, but also announced a further consultation on exempting all brownfield sites smaller than 2.5 hectares from the rules.

This would be a good move. There is a strong environmental case for building on brownfield sites within cities, yet imposing BNG requirements make them less viable for housing.

Yet there are two areas here where the Government should go further.

First, they should apply similar logic to environmental impact assessments (EIAs). At the moment, major brownfield developments (150 or more homes) often are required to be screened for EIAs and around a third have to carry out a full EIA. Other countries, like the Netherlands, have much higher thresholds for EIA screening. We should do the same.

Second, the Government should implement a suggestion from Angus Walker, a lawyer who specialises in BNG. When developments fall foul of BNG requirements by small margins (Walker suggests 0.1 units) the requirement to provide gains on-site or design off-site schemes should be waived. Instead, developers should be free to buy biodiversity credits off-the-shelf eliminating unnecessary admin.

Affordable Housing

In England, affordable housing, or as I prefer to call it, below-market rate housing is funded by the profits from private development. This is, in effect, a tax on new development. At the margin, some projects that would be worth doing without affordable housing as part of the bundle become unprofitable as a result. Fewer homes get built. This is why many studies find affordable housing rules can backfire and make new housing less affordable.

Yet there’s another problem with affordable housing. In most cases, new affordable homes must be delivered on site. This, it turns out, can be rather complicated and expensive. If you’re building on London’s South Bank then each unit you build may have a sale price of upwards of a million and an expensive service charge to boot. The same money a developer would pass up could go much further if the homes were built in less prestigious destinations.

For developments in the new ‘medium category’, the Government is consulting on giving developers the freedom to opt-out of on-site affordable housing and instead hand the money over to the council to spend on social housing. Not only would this speed up planning for smaller projects, it should also get more affordable homes built where they are most needed.

***

Most ideological groupings appear like homogenous blobs from the outside, but actually contain important differences of opinion. YIMBYs are no different. There might be agreement on the end-goals of more housing in places where effective bans on building have made it unaffordable, yet there’s a big dispute on how to get there.

Some believe the answer is to ‘crush the NIMBYs’. Or phrased less aggressively, to design a rational system and hope voters reward you for higher rates of growth and more affordable rents. Japan’s flexible zoning policy is typically held up as what we should aspire to. Others take a more cynical, or they might say ‘realistic’ view of the political economy of planning policy. They might like to ‘crush the NIMBYs’ but deep down know that when push comes to shove, the NIMBYs are more likely to crush them. They place less emphasis on what an ideal system might look like and spend more time trying to figure out the best way to incentivise people to say yes to development. Our planning constraints are so bad currently that relaxing these slights unlocks a big windfall that, in theory, should be able to buy-off all sorts of opposition. They see the route out of the housing shortage in policies like estate renewal, where every resident on a council estate gets a new more spacious home funded by market-rate housing built at high densities on the same site, and street votes, where an entire street can vote themselves rich with each household granted the right to build up.

This new NPPF is, in essence, a test of how far you can get with NIMBY-crushing. There will inevitably be a large backlash. Anti-development NGOs are already attacking the plans and MPs can expect their inboxes to be filled with angry letters co-ordinated by groups like the Campaign to Protect Rural England. But if they hold their nerve, the reward is massive: an end to the worst housing crisis in the Western World. I hope they succeed.

The 800m station radius policy is clever but I wonder if it inadvertently creates value capture problems at scale. If every well-connected station suddenly becomes a high-density development zone, won't land speculators front-run this and capture most of the uplift before councils can negotiate Section 106 deals? The New Zealand comparison is useful, but Auckland's rail network is way less extensive than the UKs, so the land value dynamics might play out diferently. Also worth noting that requiring 40-50 dph minimums is solid in theory but enforcement will be tricky when developers lobby for loopholes.

Thank you for an interesting article. It’s high time that way have a proper, functional, planning framework across England. There is a huge demand for small housing units on properties which can be rented out at affordable rents saying railway stations as development nodes makes a lot of sense, even though there will be difficulties in that. Brownfield sites which are safe to build on should be made available for non-executive Property builds. As someone who lives in a rural area, has there been any discussion to will allow building properties upon the greenbelt?