Rhetoric vs. Reality

Slogans won’t get Britain building again

If we judge governments by rhetoric alone, then this Labour Government is by a country mile the most pro-development in history.

At Labour Party Conference, a few weeks ago, Housing Secretary Steve Reed proudly wore a hat bearing the slogan: “Build Baby Build.” In fact, the most common sight at the Conference was Reed signing hats for Labour-supporting YIMBYs.

The Chancellor has taken a similarly strong line. In response to a question about whether the Government’s planning reforms were sufficient to get rid of 350,000 page planning applications, she stated:

“I am afraid, as a country, we have cared more about the bats than we have about the commuter times for people in Leeds and West Yorkshire. We have to change that. I care more about a young family getting on the housing ladder than I do about protecting some snails, and I care more about my energy bills and my constituents than I do about people’s views from their windows.”

Strong stuff. In theory, YIMBYs like myself should be punching the air and celebrating. But instead, I am just really stressed out.

The problem is that the Government is investing a huge amount of political capital in making the case for radical reform of planning and environmental protections, while the actual measures they put forward are insufficient to fix the problems they have identified. They are, in the words of The Economist’s Duncan Robinson, taking an ‘all pain, no gain’ approach.

Theodore Roosevelt famously advised “speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” This Government is doing the opposite. Shouting loudly, but adopting a much more moderate – they might say pragmatic – approach to planning reform.

I agree wholeheartedly with Rachel Reeves that homes for young people should come ahead of snails. But here’s the thing: the Government’s planning reform agenda doesn’t. It merely believes a win-win can be struck where snails can be protected, while homes will be built.

Months later, when she triumphantly revealed a 20,000 home development held by up snails had been unblocked, it was because a deal had been struck with the water company to abstract less from an aquifer, which, in turn, protected the Whirlpool Ramshorn Snails that drew her ire.

The premise of Part 3 of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill isn’t that we need to put jobs and homes ahead of nature, it is that we can protect nature more efficiently with less red tape by taking a strategic approach. Given the insanity of nuclear fish discos, £100m bat tunnels and 350,000 page planning applications that shouldn’t be a controversial premise.

Yet the rhetoric on bats and newts and snails and so forth has meant that opposition from green NGOs like the RSPB, Friends of the Earth, and dozens of local Wildlife Trusts has been vehement. They fundamentally do not trust that the newt-haters are actually going to do something good for nature. And their pushback has been so strong that the Government eventually amended the Bill to make it much harder to use the strategic approach. (The Lords have amended it further to essentially kill Part 3, but the Commons will almost certainly overrule them.)

My big fear is that this big moment where the PM, Chancellor, and Secretary of State for Housing (and the planning system) accept the core YIMBY analysis of what’s wrong and are willing to spend serious political capital on fixing the problems, will not produce anywhere near the scale of reform needed to build the homes and infrastructure our nation clearly needs.

And there’ll be a big backlash. People will say “Ha! We tried making it easier to build and it didn’t work. Let’s subsidise mortgages (or cap rents) instead.”

I really don’t want to be like one of those ageing Trotskyists watching the Berlin Wall fall, while making the excuse that ‘Real Socialism was never tried.’ But let’s be clear: Real YIMBYism isn’t being tried.

Some progress has been made

This isn’t to give the impression that the Government isn’t doing anything good. Bringing back housing targets and ensuring councils face serious consequences for missing them will boost supply. Higher targets almost everywhere with more homes concentrated in the least affordable places will boost supply. Making it much easier to build on the ‘grey bits’ of the Green Belt will boost supply.

And that’s not all. New National Policy Statements for major infrastructure projects will mean fewer are delayed by legal challenges. The effective ban on onshore wind in England has been lifted. Part 3 of the Planning Bill might not completely eliminate 10,000 page environmental impact assessments and £100m bat tunnels, but it will help and could solve some big problems like Nutrient Neutrality, which holds up over 100,000 homes. The Planning Bill also kills the requirement for projects like Sizewell C to run consultation after consultation just to avoid being sued. Delaying-tactic legal challenges to infrastructure projects will get one fewer ‘bite of the cherry’ in court.

London’s excessive affordable housing requirements have been cut, as have density-reducing dual-aspect mandates. Puddles are no longer a barrier to building homes!

This list is far from exhaustive either. There’s also recently been strong support for a massive expansion of Cambridge – not to mention a New Town built in the soon-to-be absurdly well-connected village of Tempsford. Planned changes to Biodiversity Net Gain could make development within cities much easier.

There’s a lot that deserves genuine credit, but none of it is sufficient to enable us to build our way out of the mess we are in. Unless further bolder action is taken, there will still be bat tunnels, fish discos, and kittiwake hotels in 2029. And instead of celebrating having built 1.5 million homes, they’ll be making excuses for why they haven’t even been able to outbuild the last Conservative Government.

We need to be clear about the scale of the problem.

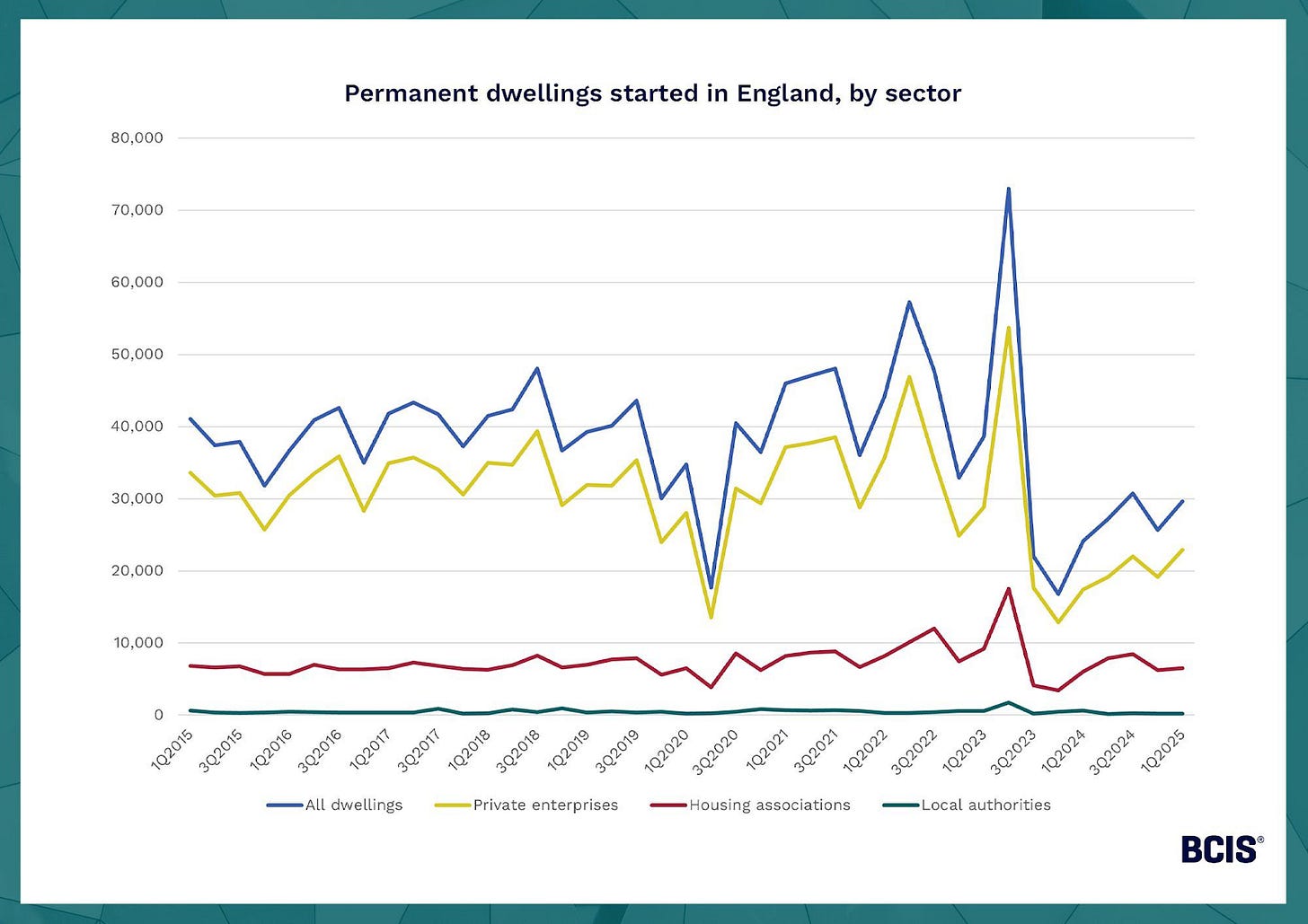

We are not building enough houses. Just 231,000 have been built in this parliament up to 14th September in England. Build at that rate for the rest of the parliament four years and Labour will fall 514,506 homes short.

Yet it gets worse, one way of forecasting future housebuilding is to look at planning applications. In 2025 between January and June developers applied for permission to build 101,822 homes. That’s down from 113,583 the year before and 131,869 the year before that. Even if every single home developers applied to build was approved and built, Labour would still be 480,000 homes short of their 1.5 million home target.

This is almost certainly an overestimate. In reality, around one in ten planning applications are rejected. Even when applications are accepted, there’s no guarantee they will be built. Projects can fall through for a whole range of reasons. Our best guess is that for every ten homes approved, only seven homes get built. Factor that in and it implies Labour won’t miss their target by 480,000 homes, they’ll miss it by 750,000. Or put differently, fewer homes will be built in this Parliament (744,483) than in the last one (790,030).

That’s nationwide, but the housing crisis isn’t evenly distributed around the country. Most extreme is London’s housing shortage where a one bedroom flat costs more to rent than a three bed in any other region. And yet in the capital, the situation.

While housebuilding was down last year by 10% nationally, it’s fallen by 70% in London. In fact. just 2,158 homes were started in the first half of this year. That’s just one-20th of what’s needed to meet London’s 88,000 home a year housing target. To put that in perspective, London is on track to build 0.24 new homes per year per 1,000 residents. Greater Manchester built more than 9 times as many per resident. Auckland in New Zealand and Austin, Texas are building at 38 and 35 times the rate of London respectively.1 The Centre for Policy Studies recently uncovered the remarkable fact that most homes built last year were approved under the last London Plan authored by Boris Johnson.

London’s planning problems are large, yet the recent drop in housebuilding isn’t the result of planning policy getting even stricter.

First, there’s been a drop in demand due to higher interest rates, continued economic stagnation, and concerns around leasehold. Many projects were approved on the condition that a substantial number of the homes built would be ‘affordable’ (either sold at below-market rates or at social rents). The issue is that while the uplift from selling new homes might have been able to fund the affordable homes a few years ago, this is no longer the case. Projects become unviable. In other words, if developers choose to build them they will make a loss.

Second, the biggest change has been the creation of the Building Safety Regulator. As a result of the Building Safety Act 2022, all new ‘higher risk’ buildings (18m or higher) must apply to the Building Safety Regulator for approval before they can be built. When the Act came into force in October 2023, there was an immediate drop in housebuilding. In theory, approval should take around 12 weeks, but was taking three times as long. A lack of guidance meant that around 70% of applications were rejected. In one case, a developer complained that one reason for rejection was that a sign was 2mm too short.

There’s a further process for newly-built buildings where BSR signoff is needed before anyone can move in. Sky News recently reported that 1,210 completed homes were stuck empty because they couldn’t get sign-off from the BSR. One reason for the slow approval rate is the BSR also applies to minor renovation works in higher-risk buildings. In one case, a homeowner who wanted to renovate their kitchen and bathroom was forced to spend £5,000 in fees and wait over a year because it involved moving a single fire door.

The Building Safety Regulator was not the only barrier related to building safety either causing problems. When he was Housing Secretary Michael Gove brought in the requirement that all higher risk buildings have multiple staircases. This cut into floorspace and meant that developers had to choose between cutting back on units or selling smaller homes (with fewer bedrooms). This exacerbated viability challenges, caused delays, and when combined with London’s requirement to maximise dual-aspect (having windows on multiple walls of each dwelling) ruled out many floor plans altogether. When the last Government assessed the costs and benefits of Second Staircase rules, they found the costs outweighed the benefits 294 times over. This, it turns out, was a gross underestimate as it assumed that developers could get around the loss of floorspace by building upwards. Of course, if builders could build up even further they would. The problem is planners and councils do not let them.

London’s high land values, lack of space, and strict planning conditions around affordability mean that a very large share of developments in London are tall and therefore high-risk under the Act’s definition.

It is still too hard to build infrastructure in Britain.

That’s housing, yet Labour’s pledge to get Britain building again was not confined to housing.

In opposition and government, Reeves and Starmer have highlighted example after example of planning rules and environmental protections preventing us from building vital infrastructure.

In a Daily Mail article, Keir Starmer directly targeted an individual who had delayed multiple major road projects in the courts. Even though the man in question was unsuccessful in every case, he still cost the taxpayer hundreds of millions of pounds in legal fees and inflation-related construction cost increases.

Reeves and Starmer have frequently expressed dismay at the fact that even though the actual construction of an offshore wind farm takes two years, it takes as long as 13 years to go from idea to generating power.

And then there’s HS2’s £120m bat tunnel that they have referenced so many times. A direct result of the EU’s Habitats Regulations and one of the key motivations for the Planning and Infrastructure Bill’s strategic approach to nature protections.

Yet while Labour’s Planning Bill does contain many worthwhile reforms, it is unlikely that they will be sufficient to consign the absurdities listed above to the history books. Removing ‘one bite of the cherry’ from legal challenges will mean fewer drag on for over a year, but campaigners will still be able to delay projects by months.

In theory, the creation of the Nature Restoration Fund and a move to ‘strategic’ compensation will put an end to fish discos and bat tunnels, yet planning lawyers have poured cold water on the idea suggesting that as drafted only problems like nutrient neutrality will be solved through the new approach.

Legal certainty from New National Policy Statements and an end to the legal duty to consult before submitting a planning application for infrastructure projects should trim the timelines for offshore wind projects, but not radically so. Nor will the planning fast-tracks for major infrastructure, which started under Gove and have continued under Labour, help. Meeting the requirements to qualify for the fast-track will likely take so long that any time savings net out to zero (or worse). At least that was the view of Catherine Howard, the lawyer Rachel Reeves has hired to advise on planning reform.

Recently, the Government put out a press release claiming they have approved a record number of infrastructure projects within their first year in office. Yet, this was less a function of their willingness to say ‘Yes’ and more of there simply being more infrastructure projects on the table for them to decide on. And after an initial flurry of approvals when they took power, decisions have come slowly. Within their first year, 14 National Significant Infrastructure Projects were delayed by ministers failing to sign off paper work on time. They have been delayed by a collective 1496 days. One of the projects Labour approved, the Cambridge Waste Water Treatment Plant, was cancelled due to cost increases. The 177 day delay is unlikely to have helped.

In some cases, the planning system is getting even more burdensome. Labour are not to blame for this. Rather the fault lies with Michael Gove’s Levelling Up and Regeneration Act creating a new duty to ‘further the aims of National Landscapes’. It has already complicated projects like the Luton Airport expansion and led to a legal challenge to a 165-home development in Kent. It is almost certain that the power lines vital to meeting the Clean Power 2030 pledge will be challenged on similar grounds.

The Lower Thames Crossing’s £300m 360,000 page planning application has become a symbol of Britain’s planning dysfunction. Yet is there any better evidence that the reforms put forward by the Government are not sufficient than the news that Heathrow estimates their planning application will cost £820m to prepare. Almost £1bn to get permission from the Government to build something that the Government is convinced is vital to boosting economic growth.

Where are Labour falling short?

There is still time for Labour to close the gap between rhetoric and policy. Yet there needs to be a recognition that what’s been put forward so far is insufficient to solve the problem that Reed, Reeves, and Starmer have correctly identified.

Specifically, they are falling short in three key areas. First, there’s the need for densification of our most productive cities. There are tools available that could make our planning system more rules-based and less bureaucratic that are being ignored. Second, the need to reform the system of environmental protection. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill is a step in the right direction, but will be limited without reform of the Habitats’ Regulations, which are the underlying cause of 80,000 page environmental impact assessments and expensive mitigations like bat tunnels. Third, there is a fundamental failure to grapple with the flawed-nature of the Building Safety Regulator, without reform here it is unlikely London will ever get building again.

Over the next week or so, I’ll be publishing posts on how to boost density, reform the Habitats Regulations, and fix the broken Building Safety Regulator.

Austin does not have directly comparable figures to London so this figure uses building permits issued in 2024, and then assumes that 80% of those building permits result in a new residence being constructed. In reality housing construction takes 6 months to 2 years and it is likely that Austin’s housing constructed was actually higher than this in 2024, as permits issued in 2022 and 2023 were significantly higher than in 2024. Various methods and data sources for generating a similar figure for Austin produced figures between 30 and 43 times higher than London’s building rate.

“Almost £1bn to get permission from the Government to build something that the Government is convinced is vital to boosting economic growth.”

Has anyone done an investigation into which consultancies are expected to benefit from this, and their ties to parliament?

If a third world country did this we’d be saying it was a blatantly corrupt diversion of public funds

I've been wondering about this. What a depressing state of affairs.